Research Arsenal Spotlight 21: Richard Ransom and the Chicago Mercantile Battery Light Artillery

Richard “Dick” Ransom was born in 1842 to Daniel Ransom and Lucy Edson (Lake) Ransom of Woodstock, Vermont. By the 1860s, Richard Ransom was living in Chicago working as a printer. On August 7, 1862, he enlisted in the Chicago Mercantile Battery and was mustered in on August 29, 1862. The battery was organized by the Chicago Mercantile Association.

Richard Ransom’s letters begin in December, 1862 while the Chicago Mercantile Battery was in Memphis, Tennessee.

Richard Ransom and Sherman’s Yazoo Expedition

On December 14, 1862, Richard Ransom began a letter to his family telling them about his current situation in camp. At the time, Union forces were massing in large numbers in preparation for Sherman’s Yazoo Expedition, where the General would bring a large number of troops down the Yazoo River in hopes of breaking through Confederate defenses and bringing the Union closer to seizing Vicksburg, Mississippi.

Richard Ransom’s concerns were less concerned about the battle to come and more concerned with what the large number of troops meant for soldiers’ daily rations, as he explained in his letter:

“We can draw no soft bread at all here now. There is such a large army here, it cannot be baked for them. There has a large army concentrated here since we went away—some say about 30,000 and some say as many as 60,000. And this evening I heard that no boats were allowed to return up the river [and] that all boats that landed here were taken possession of by Government for the purpose of transporting us down the brook—even all the small boats. So you may not get any news from here for some time.”

In a letter written December 25, 1862, Richard Ransom detailed some of the destruction left in the wake of the expedition, by soldiers sneaking off to burn towns as the ships sailed south:

“Tuesday, 23rd, we went as far as Gaine’s Landing, Arkansas, and tied up for the night. The place was begun to be burnt before dark and kept up all night and in the morning but one or two houses were left. Gen. Smith ordered that the men that set the fires be tied hand and foot and thrown into them or if the fire was burnt out when they were caught, he would throw them tied into the river—and if one was caught before two o’clock in the morning, he should be hung and one was caught and brought in and he told him he should be shot at two o’clock next day. But before the time came, he told him he might go—that Gen. Sherman had pardoned him and gave him a good talking to but let him go.”

Richard Ransom and the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou

On December 27, 1862, Richard Ransom wrote home informing his family that he had likely caught the measles:

“I have a few minutes more before the mail leaves us and I must tell you how I get along. I believe I wrote you in the other letter that I felt ague-like. Well, I have got no better but am able to be around and help myself as well as ever, but I expect to have the measles. There has been a man lying on deck three or four days who has them and some of our boys knew it so we have been much exposed. If I do take them, I know what to do. Keep warm, and shall not be kept out on deck as that infantryman was. He was taken to the hospital boat this morning.”

Richard Ransom was also frustrated with the leadership of members of the regular army, which he felt were too soft on Confederate forces:

“I can but distrust the loyalty of all the old “regular army” officers. Gen. A. J. Smith now has about 20 secesh prisoners on board this boat and they are fed at the cabin table on hot rolls, beef steak, &c. &c. while we boys have to eat on hard tack or pay fifty cents a meal. Some of them are also allowed staterooms.”

Included in the same letter but written on January 3, 1863, Richard Ransom then gave an account of the disastrous Battle of Chickasaw Bayou. Richard Ransom prefaced the summary with the warning, “Where we have been and where I have been and what we have seen in the past week had made me wish to be at home.”

The troubles began with the unloading of the battery from two ships which left a mess of confusion. Ransom described it:

“I will give you a diary of the week. Saturday afternoon, December 27th, we passed a lot of gunboats &c. anchored at the mouth of the Yazoo and the transports of our Division went up the Yazoo River between ten & fifteen miles where we found the balance of the transports of our fleet having all been unloaded and the troops put out towards Vicksburg—through the swamps—and we could occasionally hear a cannon shot and sometimes a sound which I supposed was the mortar boats in the Mississippi River, shelling the city.

Our two guns were got off the “Des Arc” and the drivers brought the horses up from the “Louisiana” and we joined the rest of the battery—and the Louisiana was unloaded and we had everything mixed up on the levee in such a shape as never was known before. The battery could not have been got ready for action in less than five hours. We had orders to be ready to march in the morning at seven o’clock with two days rations of “hard tack” (nothing else to take) and only take one blanket and no baggage. Everything was to be left in camp and all the sick to guard it. Then I was a little afraid because I had not been well enough to unload the boats and hardly to carry my own baggage ashore—and was growing weaker all the time—had eat nothing for two days—had a fever and was afraid of the measles and didn’t think they would let me go. The firing was kept up in the distance and news of all sorts was flying about.”

Eventually the Chicago Mercantile Battery arrived near the fighting and Richard Ransom resumed his account:

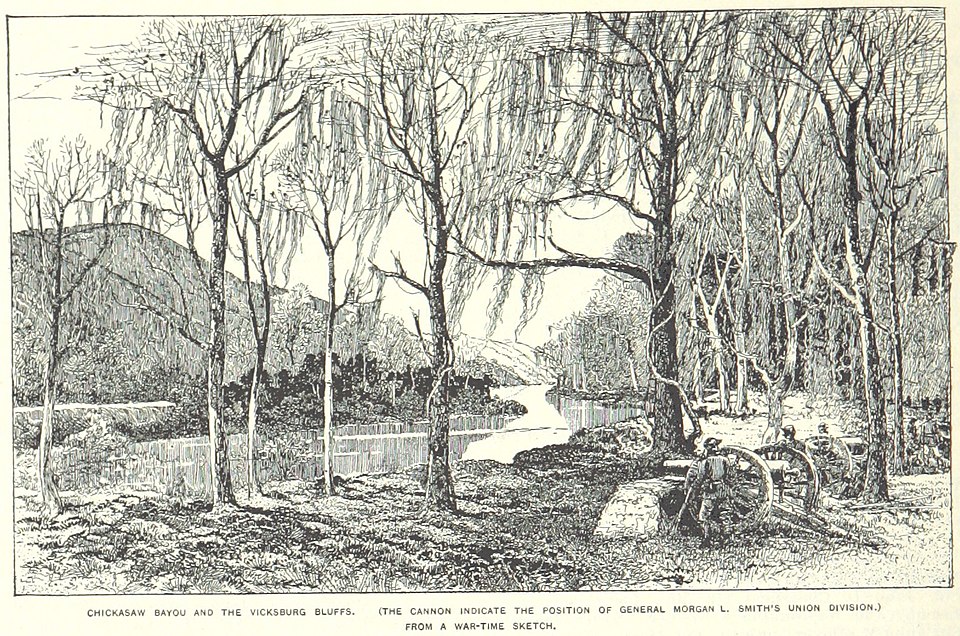

“We finally stopped in the woods I should think about eight miles from the boats, and nearly north of Vicksburg—the city being in sight from a short distance from us, and we could “hear the bells.” Where our guns were planted down on the “river bottoms” in the woods, the water marks on the trees for high water was eighteen feet above the ground and was so for the whole distance back to the Yazoo. Where we lay there we were only about a mile west of the Mississippi and the fighting was between some of our big guns on the west of us and some batteries across a bayou, on the hills, which we must take to get into Vicksburg. I believe that our artillery beat them on Sunday morning and the infantry all were drove into Vicksburg, and we had the hill. Here Morgan L. Smith was wounded leading a charge across the bayou where the men hesitated to go. He got a bullet through his belt in front and it lodged between two bones in his back and he had had to give up command of the 2nd Division. Then our A. J. Smith took his place and Brig. Gen. Burbridge took this—the 1st Division.

Before noon we heard a good deal of heavy firing of infantry—volleys and single shots—and finally it all ceased, and not much more was heard till next morning, though an occasional big gun would start us a little, for we lay where they could shell us all to pieces from Vicksburg.”

At this point Richard Ransom’s health had deteriorated substantially because of the measles and he was forced to go to the hospital to recover. On January 3, he received word that they were to withdraw:

“Soon Sergt. [Pinckney S.] Cone came and I found out that the whole army was going to be drawn back and put on the boats before morning—quietly and in order. [Frank S.] Wilson’s Section was to start at 12 o’clock, [James H.] Swan’s at 2, and [David R.] Crego’s at 4 o’clock. All the caissons started together as soon as the order was received, and the boys tell me that the pickets came in and the last of all the infantry ready to step off about half past three. But orders were orders and they had to stay till 4 o’clock without any pickets beyond them, and then too, the pickets who came in reported that the rebels were building bridges across that bayou we had been fighting over and probably intended to cross and attack us in the morning. There was nothing came in behind our two guns but one regiment of infantry and they report that rebel scouts followed right behind us clear in to the edge of the woods but not out on the cornfield between the woods and the river. So you see we covered the great retreat.”

Richard Ransom in the Hospital

Even as Richard Ransom recovered from the worst of the effects of the measles, he remained weak and in the hospital, though he was always quick to reassure his family that he was not as sick as they feared. He also tried to avoid the doctors and medicine as much as possible, believing that it would make him sicker, as he described in a letter dated March 22, 1863:

“My cough is all gone and I am so to speak “quite well”—though weak. I still keep away from the doctors and everybody who says anything to me about it advises me so to do—at least to take as little medicine as possible.”

On March 24, 1863, Richard Ransom received a discharge for disability due in no small part to the efforts of Mrs. Mary Ashton (Rice) Livermore, who was down visiting the hospital on behalf of the Sanitary Commission. He described her efforts in a letter dated March 20, 1863:

“Mrs. Livermore said she was bound to take me home with her. She knew she could get me discharged from the service and she should do it. I got certificates of disability and got the papers properly started and gave them to her and she will do what she can about getting them through headquarters. The disability consisted (so the certificate says) of “chronic pleurisy & chronic enlargement of the spleen.” The examination I went through to get the papers was—really—none at all, and the certificates were given as a favor to one of our boys—Charles H. Haight, who is very intimate with the Drs. and has a good deal of influence with them. So you see that really, I am not entitled to them, so you need not borrow trouble and think I am so very bad off.”

After the war, Richard Ransom lived for a time in Denver before later moving to Milwaukee where he lived at the Northwest Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. He died on April 3, 1917.

We’d like to extend a special thanks to William Griffing of Spared & Shared for his work in sharing and transcribing these letters.

If you’d like to read more of Richard Ransom’s letters, or see thousands of other Civil War letters and documents, sign up for a Research Arsenal membership.

You can also check out some of our other Spotlight collections like Biddle Boggs of the 80th USCT Infantry and associate of General Frémont and Varnum Valentine Vaughan of the 53rd Massachusetts Infantry.