Research Arsenal Spotlight 15: David Walker Beatty of the 63rd Pennsylvania Infantry

This week we’re going to focus on a collection of 48 letters written by Private David Walker Beatty of Company K, 63rd Pennsylvania Infantry. David Walker Beatty was born 1…

Research Arsenal Spotlight 14: Alfred Homer Johnson of the 30th Georgia Infantry

This week our spotlight is on a collection of five letters related to Alfred Homer Johnson who served as a private in Company F of the 30th Georgia Infantry. Alfred Homer…

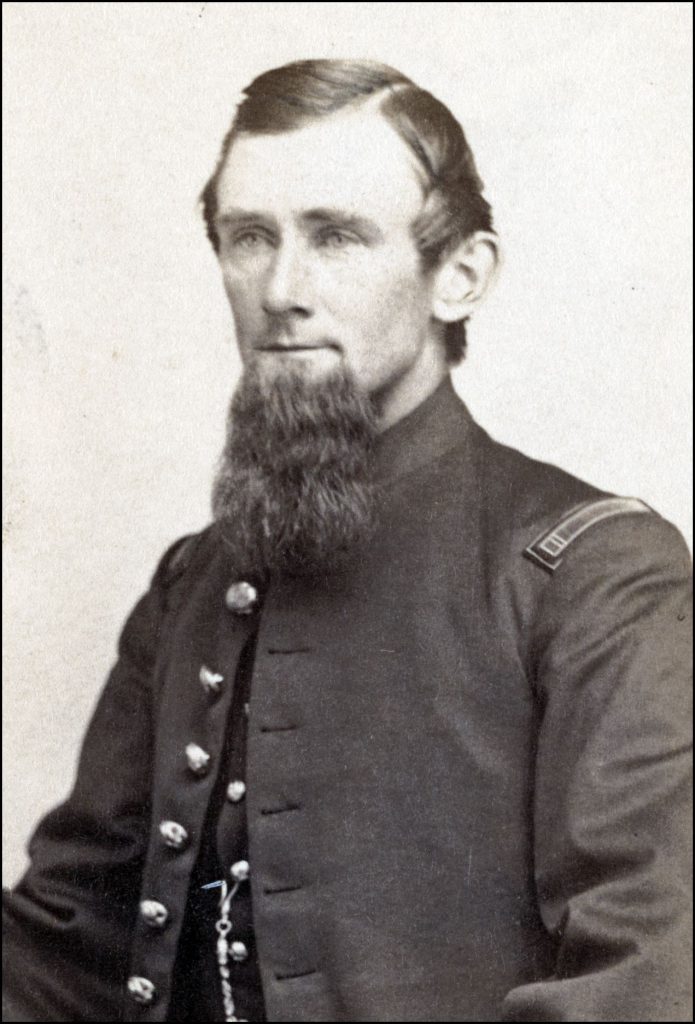

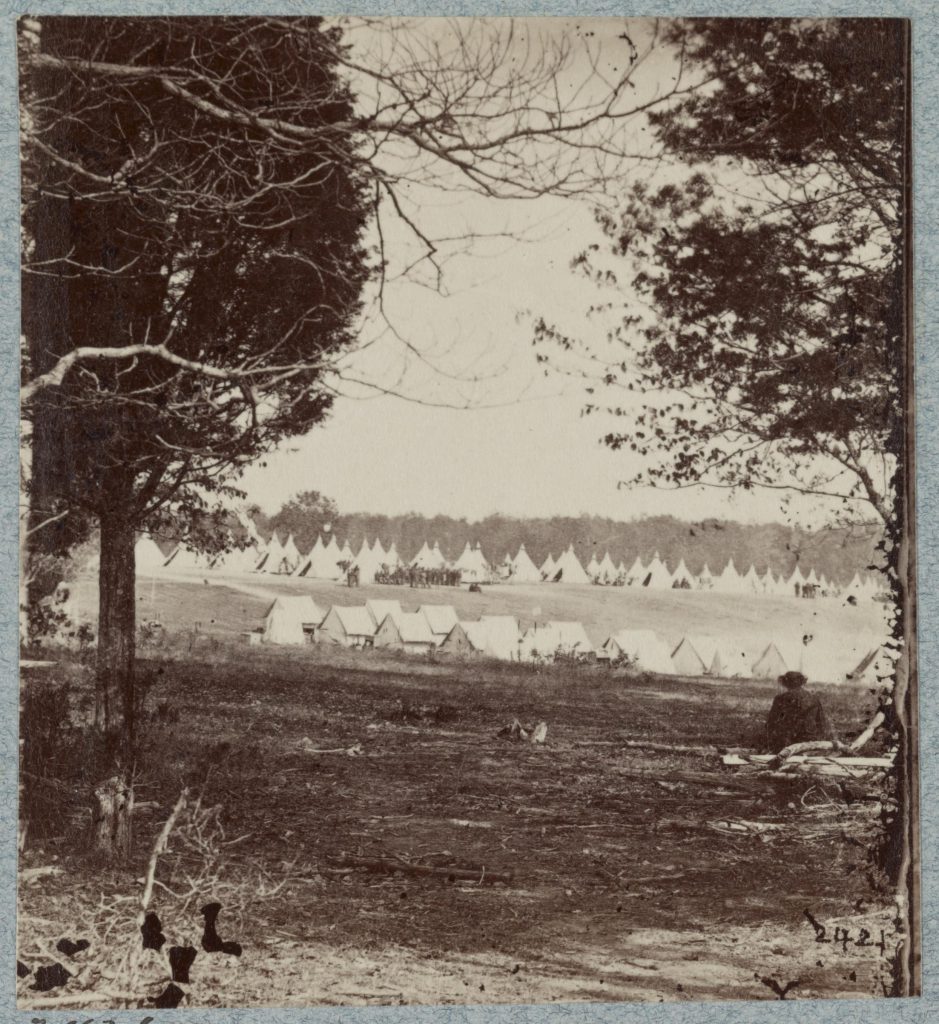

Research Arsenal Spotlight 13: 25th Ohio Infantry Photo Album

This week, we’re taking a look at a photo album of members of the 25th Ohio Infantry. The album contains fifteen cartes de visite (CDVs) of men in the regiment and most of t…

Research Arsenal Spotlight 12: Rufus P. Staniels 13th New Hampshire Infantry

Rufus Putnam Staniels was born in 1833 in Chichester, New Hampshire to Charles Herbert Staniels and Elizabeth N. (Johnson) Staniels. He enlisted in Co. C of the 13th New…

Research Arsenal Spotlight 11: US Cavalry Returns

The Research Arsenal is proud to announce that we recently uploaded all of the Civil War era cavalry returns for the 1st-6th US Cavalry. These returns encompass rolls 4, 5,…

Research Arsenal Spotlight 10: Edward Horatio Graves and the 10th Massachusetts Infantry

Edward Horatio Graves was born in Easthampton, Massachusetts in 1839, the son of Horatio Nelson Graves and Martha (Arms) Graves. His father died in 1852. The Research Arsenal…

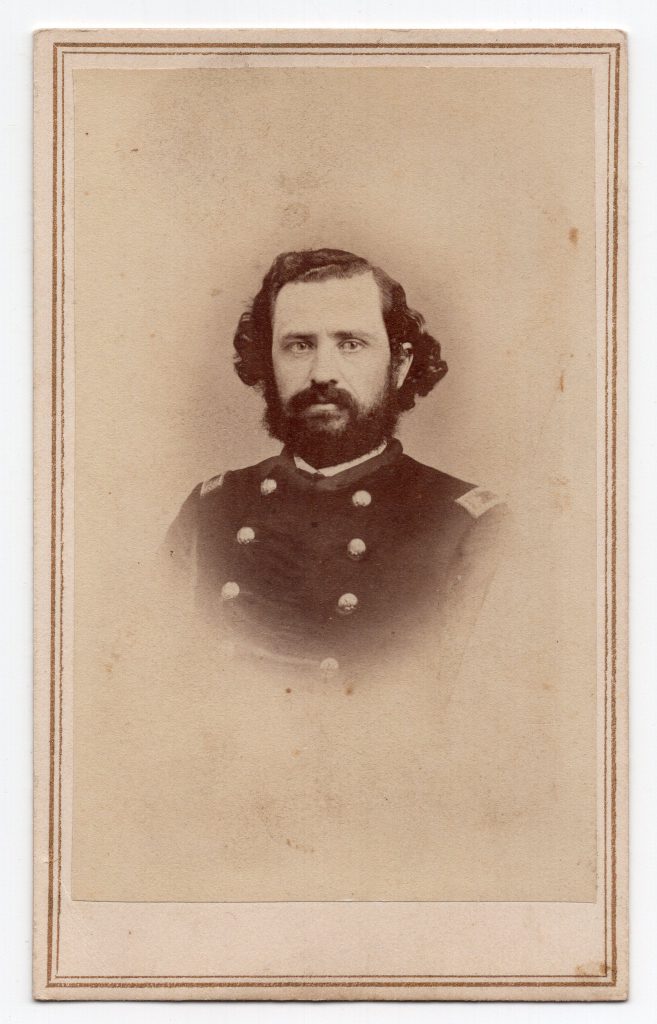

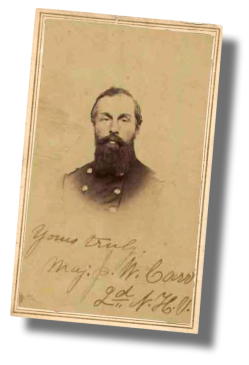

Research Arsenal Spotlight 9: James Webster Carr of the 2nd New Hampshire Infantry

James Webster Carr initially served as Captain of Company C, 2nd New Hampshire Infantry. By the end of his three-year term of service, he would be promoted to Lieutenant…

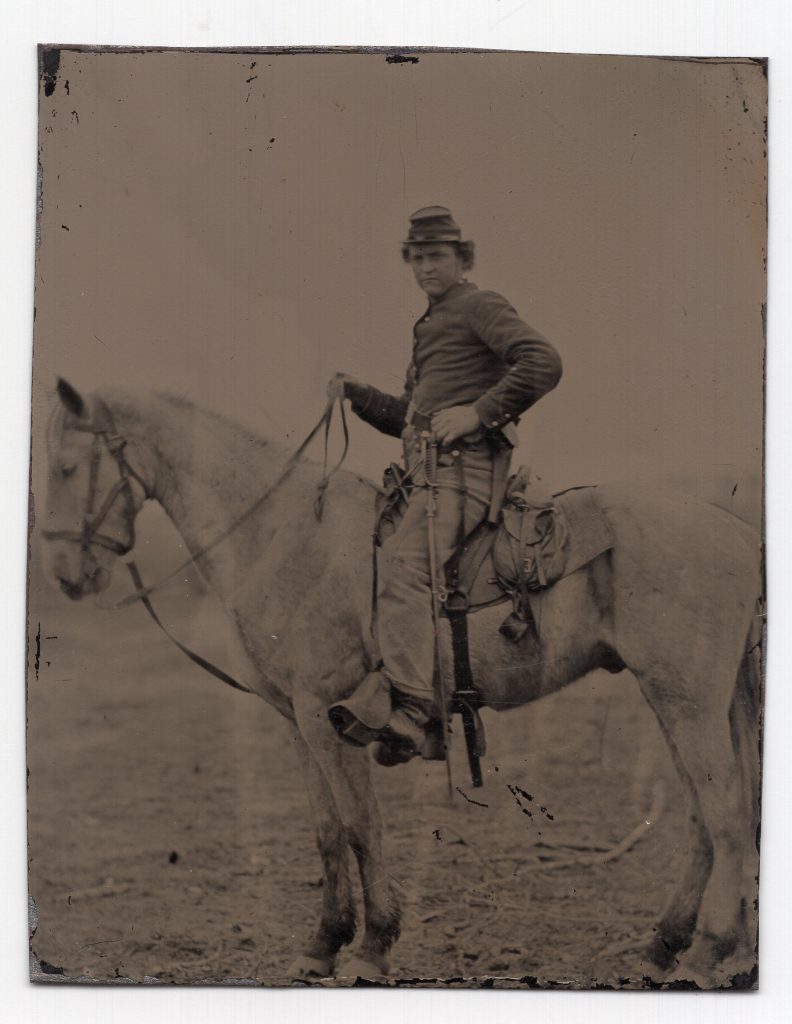

Research Arsenal Spotlight 8: Asa Frank Chester and the 20th Illinois Infantry

Asa Franklin “Frank” Chester enlisted as a private in Company G of the 20th Illinois Infantry in June, 1861. By the time he mustered out in July of 1865, he had become adj…

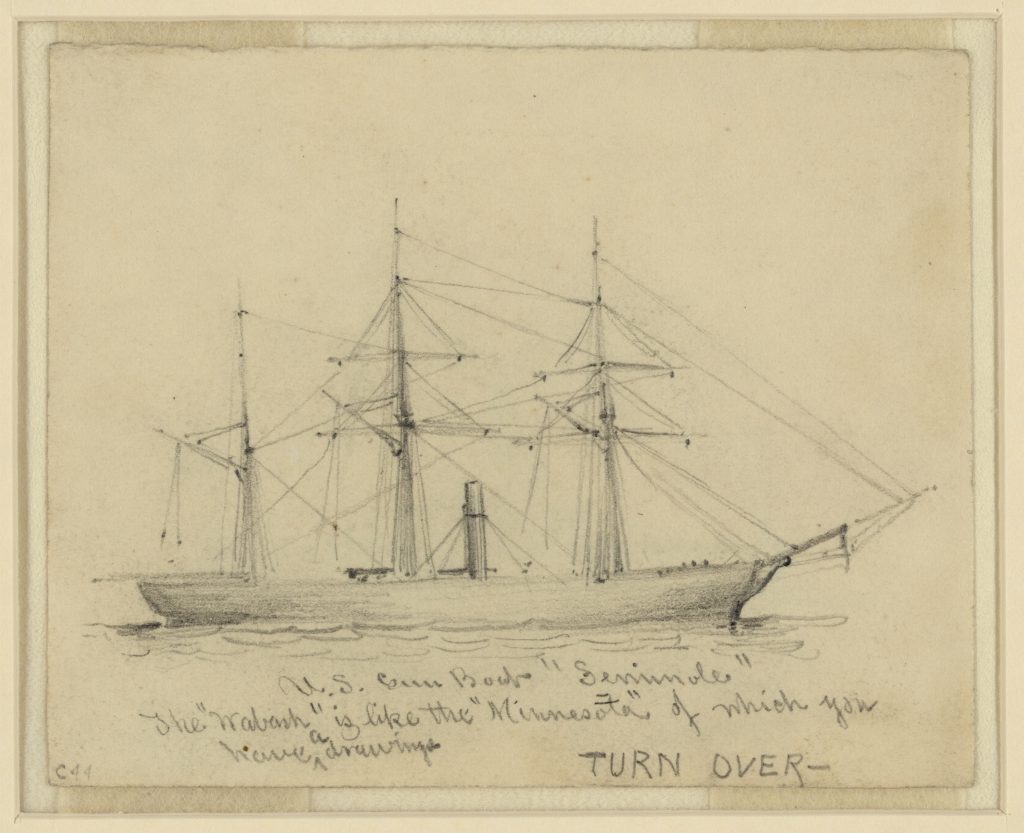

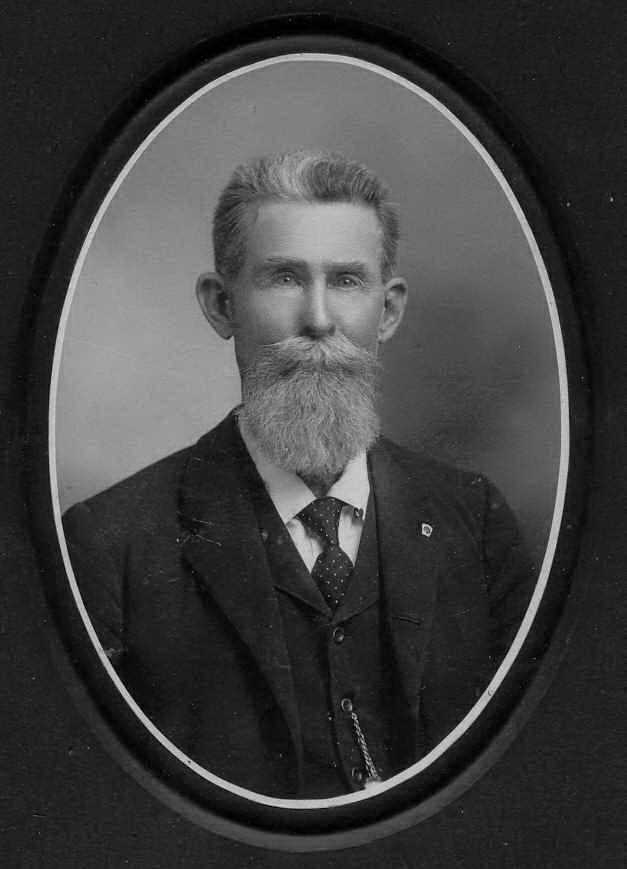

Research Arsenal Spotlight 7: David King Perkins of the USS Seminole

David King Perkins was born in 1843 to Clement T. Perkins and Lucinda (Fairfield) Perkins of Kennebunkport, Maine. On January 30, 1863, he enlisted in the US Navy as a…

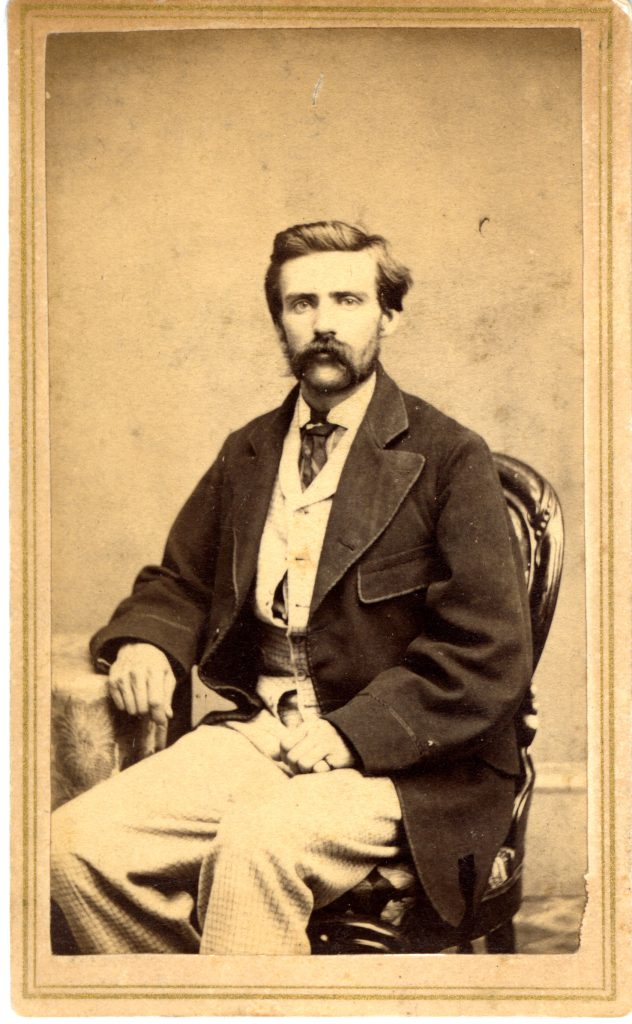

Research Arsenal Spotlight 6: James A. Durrett of the 18th Alabama Infantry

James A. Durrett was born around 1840 to John Andrew Jackson Durrett and Anne (Beauchamp) Durrett. James A. Durrett, along with his brother Thomas Jefferson Durrett…