Research Arsenal Spotlight 37: Richard Weld 44th Massachusetts Infantry

Richard Weld was born in 1835 to Aaron Davis Weld and Abbie (Harding) Weld of West Roxbury, Massachusetts. He attended Harvard University and graduated in 1856. After a short stint in the Boston Infantry Cadets in the summer of 1862, Richard Weld enlisted in the 44th Massachusetts Infantry on September 12, 1862 and was commissioned as first lieutenant of company K.

The five letters in this collection were written by Richard Weld to his sister-in-law, Anna T. Reynolds. Serving alongside Richard Weld in the 44th Massachusetts Infantry, was Frank Reynolds who was Anna’s brother and the husband of Richard’s sister, Cordelia.

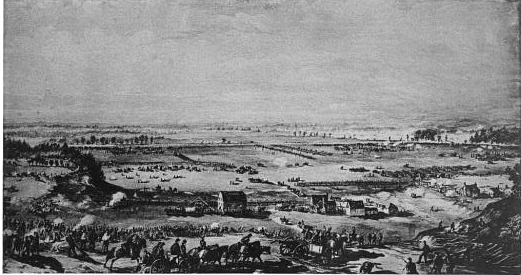

Meeting of the 45th and the 44th Massachusetts Infantry

In Richard Weld’s first letter to Anna, written one November 15, 1862, he described a meeting between the 45th and 44th Massachusetts Infantry regiments. Both were nine months regiments, but the 44th Massachusetts Infantry had already seen some fighting by the time they met up with the 45th Massachusetts Infantry in North Carolina, though Richard Weld admitted that their tales may have been a bit embellished.

“The 45th Regiment got here last night and our regiment took care of them. [John] Frank Emmons and Alpheus [H.] Hardy slept in Frank and Fred’s bed, and Fred went into the barracks to sleep. I have seen almost all the officers. They have almost all been in to call on me and it seemed very jolly to see them all again. They are going into Emery’s Brigade and will be about 3 miles from us on the other side of the river so that we shall hardly ever see any of them unless we meet by chance in the city. I tell you, we rather astonished them by our tales of marches and battles, which of course we made as glowing as possible. I was perfectly astonished with what indifference I stood there when the firing was going on on the evening of the skirmish. I had a perfectly resigned feeling if I was going to be hit, it was alright. It didn’t seem to trouble me at all.”

Campaign in North Carolina

In December, 1862, the 44th Massachusetts Infantry fought in a series of engagements as part of General Foster’s expedition to Goldsboro. In a letter written on Christmas eve, 1862, Richard Weld summarized their recent fighting, which included battles at Kinston, Whitehall, and Goldsboro Bridge.

“Saturday we did not march far as our advance was skirmishing and fighting with the enemy’s skirmishers. Sunday we had the fight at Kinston and though we did not fire again, we were where the balls were pretty thick and had to march through all the wounded and dying. They were as cheerful as if they were on a pleasure excursion, telling us to go in and whip the devils and not minding their own wounds in the slightest.

The enemy broke and ran just as we got onto the field, retreating across the Neuse river and setting fire to the bridge which they had previously tarred. Our troops were too quick for them, however. We saved the bridge and took about 400 prisoners. We crossed over the river and slept that night in Kinston, which is a very pretty village. It is hardly large enough to call it anything else.

Monday we had a long march of 17 miles and were pretty well tired out. My feet were wet through all day and in fact for most of the ten days I hardly ever had dry feet in the daytime. Tuesday was the fight at Whitehall. We were drawn up on one side of the river behind a fence and the enemy were in the woods on the other side in the trees and out of sight so that we could only fire at random, without certainty of hitting them. They were mostly sharpshooters and it was wonderful that there were not more killed. We lost 21 killed and wounded in the regiment. I lost one man killed. The enemy soon discovered our Colors and the bullets flew around and over our heads in a most unpleasant proximity. [Capt.] George Lombard [of Co. C] and myself, being the nearest officers to the Colors, were particularly favored. We stayed there about two hours and it gave our men an excellent opportunity to use their guns and get used to firing which they had never done before. We marched a few miles further that night and halted.

The next day went to the Neuse river bridge which we burnt and tore up the railroad & this cut off the communication with the South for the present. Started on our return at ½ past 5 o’clock. We heard firing again in our rear and orders came to countermarch. You can not imagine the perfect feeling of despondency which came over all of us, tired as we were, at the thought of having to march all the way back again and perhaps have another fight. We marched back about 2 miles and then were drawn up by division in the woods at some crossroads. I almost wish we could have had a fight then. We were so cold and tired and mad that we should have fought like tigers. We stayed there about ½ an hour and once more resumed our homeward way and reached the campground of the previous night about 11 o’clock. The next three days we marched back about 65 miles and reached Newbern perfectly used up. I hope I should never see such marching again.”

Leisure in Camp Life

In January 27, 1863 the 44th Massachusetts found themselves in camp without much active fighting. To fight the tedium, they turned to throwing a dance, with some of the soldiers standing in as women in a rather elaborate fashion. Richard Weld described the dance in a letter to his sister-in-law.

“The idea of dancing—how could you know my feelings so, Annie, by mentioning such a subject? I suspect that the Marching Cotillion will be the fashionable dance when we get back as we shall have unwisely forgotten all the other dances. However, I will try not to forget the gallop, for my “cousin.” The other night they had a ball in Co. E barracks—a master and fancy ball combined. Some of the men made very handsome ladies. The dresses were got up capitally considering the means at hand. Shelter tents were the chief material and being of a party color (white), they made a very pretty show. Some three or four were really artistic in their performance, putting on the airs and ways of female loveliness to perfection and causing shouts of laughter. All the officers were there as lookers on, from Colonel down and quite a number from other regiments. One female of color was a feature of the occasion and he acted his part capitally. Then men’s dresses were good also—clowns and Spanish Hidalgos being prominent. The whole affair went off in the best spirits and was a perfect success. One of the 10th Connecticut officers said they had to come over to our regiment to see any life. Some of the ladies wore very pretty headdresses and one had very luxuriant flowing hair made of long grey moss of the country.”

In February, 1863, Richard Weld wrote to Anna about a recent bill that might have seen the nine months men being forced to serve a longer term of enlistment. Needless to say, he and the rest of the 44th Massachusetts Infantry were quite opposed to it.

“It is reported here today that Wilson has introduced a Bill to keep us out here for two years. Is it so? And if so, how does it strike you all? Instead of four months more, it will be nineteen months more—some difference I must confess. I suppose it will meet with hearty approval at home as it will save some of the lazy and indifferent ones from any fear of a new draft, but won’t there be some growling out here. I believe it will make a general row (a new general) in the army if they try it on 19 months. I shudder at the thought. We should all be perfectly demoralized by that time. I shall get sick right off and have to resign.”

Despite his fears, Richard Weld and the rest of the 44th Massachusetts Infantry mustered out at the end of their original nine months term on June 18, 1863. Richard Weld married Laura Townsend on Winsor on July 3, 1866. He died at the age of 75 in 1908.

We’d like to give a special thanks to William Griffing of Spared & Shared for transcribing and sharing these letters.

To read more of Richard Weld’s letters as well as thousands of other Civil War letters and documents, sign up for a Research Arsenal membership.

If you enjoyed this article, check out some of our other featured collections like David McGowan of the 47th Illinois Infantry and Aaron Wheeler of the 50th Illinois Infantry.