Research Arsenal Spotlight 39: Samuel Huntingdon 100th New York Infantry

Samuel Huntingdon was born in 1829 and lived in Carrollton, New York. He was married to Elizabeth “Libby” Desire (Fuller) Huntingdon and the couple had three children: Adele, Milford, and Ruba. In 1863 Samuel Huntingdon was drafted into company A of the 100th New York Infantry.

Drafted Men vs. Substitutes

When Samuel Huntingdon was first drafted in the fall of 1863, he spent some time waiting to be assigned to a regiment. While getting equipped at the barracks in Dunkirk, New York, Samuel Hunting observed some of the differences in how drafted men and substitutes were treated, which he shared in a letter written on October 9, 1863.

“I have got my clothing. I have got my boots taped and going to wear them. The provost marshal thought it best they let drafted men go where they are a mind to go but the substitute cannot wink without they watch him. I have got a letter of recommend[ation] from the provost marshal to go into any regiment I may choose at Elmira. We start for there tomorrow morning. The provost said I might act as one of the guard to take care of the substitutes. Mr. Beardsley told him that I could be trusted in any spot or place.”

By October 11, 1863, Samuel Huntingdon had been sent on to Elmira with many of the other drafted men and substitutes. Once there, he hoped that his rheumatism would allow him to be sent home without having to serve. Much like in Dunkirk, men serving as substitutes were not trusted.

“I [have] been well since I left home. I think that I shall have the rheumatism so I cannot do duty for my right shoulder feels some sore this morning. When we left Dunkirk, the drafted me had all the liberty that anyone could ask. There is no examination to be had here. I understand there to be one at Alexandria and I may be sent home but do not expect too much…

…Tell George I am glad I did not let him go as substitute for they show them no mercy at all.”

Samuel Huntingdon’s hope for an early discharge continued as evidenced in a letter written on October 16, 1863.

“They are sending back so many of the drafted men from Washington that they will have a board of examination here, so the head doctor told Brown that they would be here in a few days—I think next week. I think that was the reason why we did not go. My back troubles so I think I shall get clear but do not think too much of it, but hope for the best.”

Despite his hopes of going home, Samuel Huntingdon found himself assigned to the 100th New York Infantry and at Morris Island, South Carolina by the end of the month.

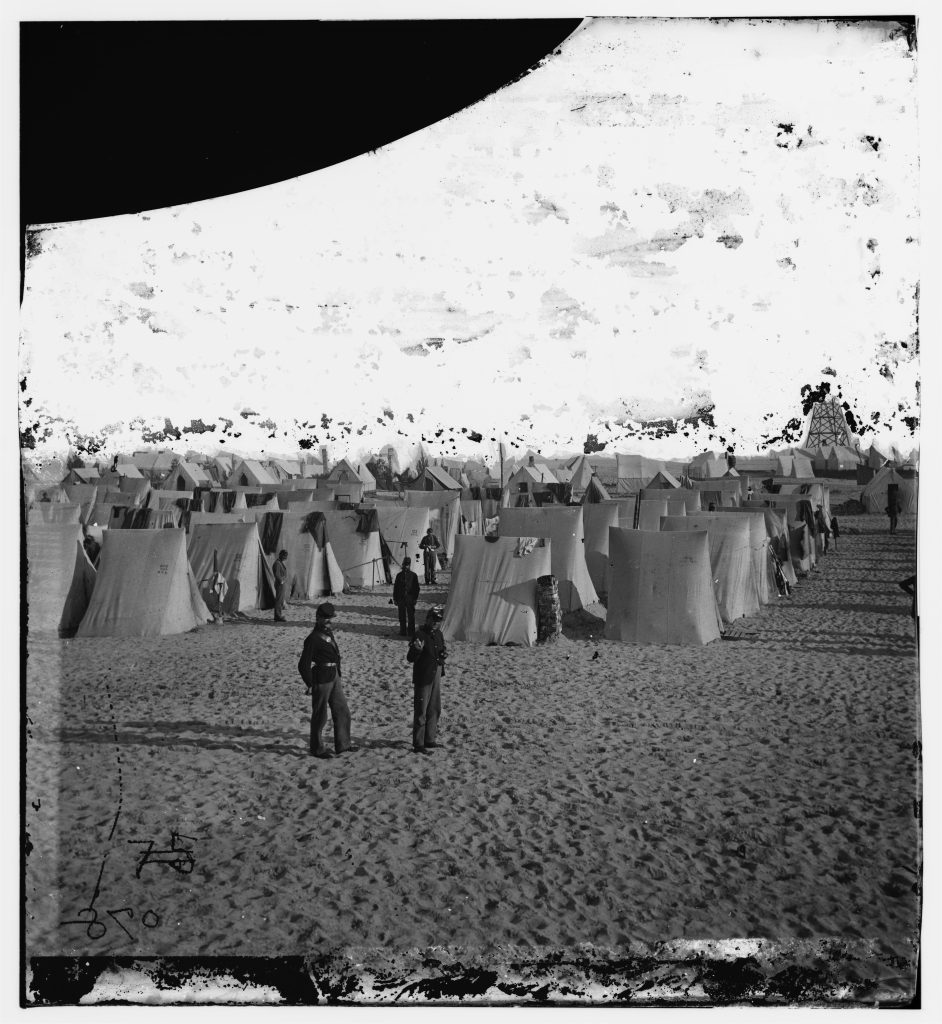

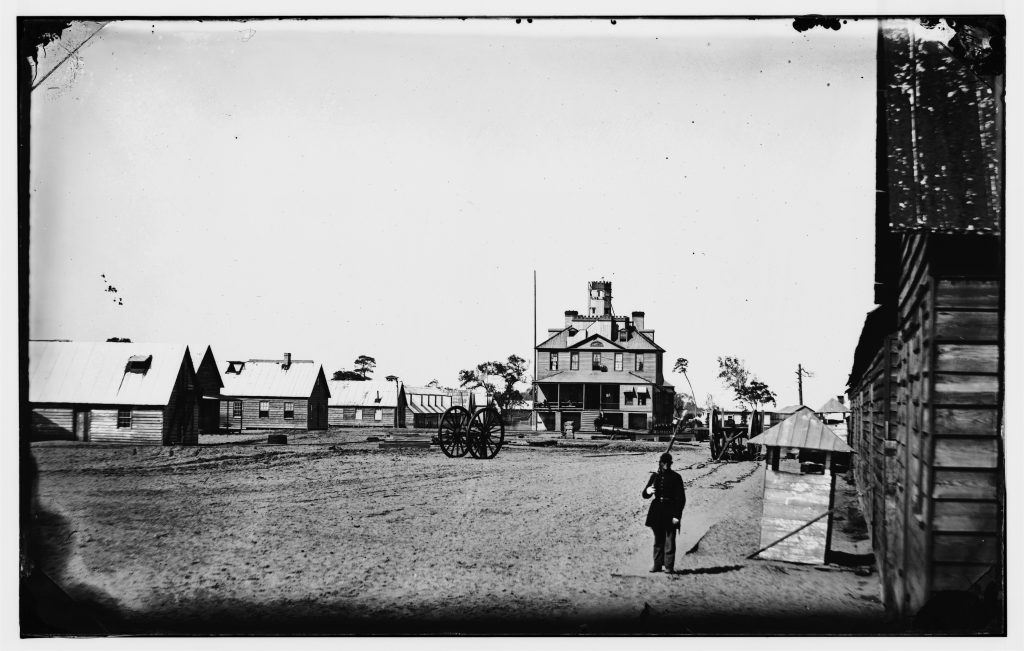

The 100th New York Infantry at Morris Island

On October 29, 1863 Samuel Huntingdon wrote to his wife about his current location and the regiment to which he had been assigned.

“We are assigned to the 100th Regiment New York. I think we shall stay here until Charleston is taken. I think it is very healthy here. This regiment has not lost but a very few men by sickness since it came here last spring. We had a very good time in coming here. The vessel rolled some but it did not make [me] sick. We was five days on the water. We are in hearing of the guns at Fort Wagner and they are firing on Sumter night and day all the time.

This island [is] nothing but sand and my feet sink into the sand as it would into snow. The weather is fine here now—like the last of September at home. We went to Hilton Head first and then back here. I can hear the cannon as I write up to the head of the island. Their second examination to be had. If I was a single man, I think I would like the service first rate. But I have a home, wife, and children that [I] cannot forget and would not if I could for they are all in all to me.”

Most of the time Samuel Huntingdon and the 100th New York Infantry faced routine duty on the island, with occasional clashes with Confederate forces, as he described in a letter written on November 22, 1863.

“Our folks keep firing at the rebs and they fire back sometimes but do not hurt. We was all called out one night and went up to the front but there was no one to hurt us when we got there for the rebs did not come over. I saw the rebs fire a number of shells but they done no hurt. They looked splendid in the night. In the morning we came back to our quarters. We was in Fort Wagner.”

Samuel Huntingdon Misses Home

A common thread through all of Samuel Huntingdon’s letters is how much he wants to return home to his wife and family. Though he did his duty and never entertained any thoughts about running away, he nevertheless wished to return home as soon as he could. He also turned to religion to comfort him that he might soon be reunited with his family.

On February 7, 1864 Samuel Huntingdon shared with his wife that he often dreamed about going home to be with them.

“I dreamed of being at home and seeing you, It was not on a furlough either. I often dream of being North and seeing you. I dreamed of getting my box last night but it was a dream. But do not worry about it, dear one. It will come in a good time for I only had two left. I sent one letter to you without a stamp. I send all of them to George without stamps. I shall keep them for you for they can pay the postage, I think, on without whining. I know them well enough for that. I shan’t pay them out for anything if I can help it. I don’t think we shall get our pay till the last of March but can’t tell. We can’t tell anything as we hear it from the North or from our homes. Let us take all things for the best and trust in God for He alone can deliver us from this trouble.

Dear one, then let us not give up never, but try to serve Him in all things though the times may seem dark, yet there is a fair day after a storm.”

Samuel Huntingdon also spent some of his free time making gifts for his wife and children. He wrote that he made each of them rings out of coconut shells and would be sending them along.

“I have made each of you a ring out of coconut shell and I will send them to you in this letter. You can divide them to suit your fingers if you can. I don’t know as you can wear them. If you can’t, you can keep them till you can, They are pretty tuff stuff and hard. I may send you something else some time but could not think of anything else now. The largest one I made for you, dear Libby, & I have worn it some on my little finger on my right hand. I thought it would be right for one of your fingers.”

In Samuel Huntingdon’s final letter in our collection, written on March 3, 1864, he lamented that he didn’t realized how blessed his life was before he was drafted into service.

“When I was at home, I did not realize the blessings that I enjoyed. There is no children here to while away an hour with or a dear companion to talk to, but all is for war—for one man to kill his fellow man in order to gratify a few. But it seems as though it was most played out and I hope it is from the bottom of my heart.”

Sadly, Samuel Huntingdon was never able to return home. He was captured at the Battle of Drewry’s Bluff, Virginia on May 16, 1864. He died of chronic diarrhea at the parole camp in Annapolis, Maryland on December 21, 1864.

We’d like to thank William Griffing of Spared & Shared for transcribing and sharing these letters.

To read more of Samuel Huntingdon’s letters as well as access thousands of other Civil War letters and documents, sign up for a Research Arsenal membership.

If you enjoyed this article, check out some of our other featured collections like Amasa Hammond of the 3rd Rhode Island Heavy Artillery and Richard Weld of the 44th Massachusetts Infantry.