Research Arsenal Spotlight 43: Joseph Maitland 95th Ohio Infantry

Joseph Maitland was born in 1838 to James Madison Maitland and Anna (Mast) Maitland of Salem, Ohio. Joseph Maitland enlisted in Company G, 95th Ohio Infantry on August 8, 1862 and was appointed corporal on August 19, 1862. On December 5, 1862 he was promoted to sergeant.

In 1862 Joseph Maitland, along with much of his regiment, was taken prisoner at Richmond, Kentucky by Confederate forces under the command of General Kirby Smith. He was paroled and sent to Columbus Ohio for about three months until the end of 1862.

For this spotlight we’ll focus on the 13 letters he wrote in 1864 to his future wife, Arabella Wharton.

The 95th Ohio Infantry in Tennessee

In Joseph Maitland’s first letter in our collection, he wrote from a camp near Memphis, Tennessee on May 11, 1864 about the recent expedition the 95th Ohio Infantry had made in the area.

“After proceeding about 34 miles east of Memphis, it was found that the bridge over Wolf River had been destroyed so that we could go no further that way, so we abandoned the railroad and proceeded to take up our line of march on foot. Our course was in a southeasterly direction passing through the towns of Moscow (which is nearly all burned), Somerville & Bolivar. At the last named place, our cavalry — which was in the advance — overtook a part of Forrest’s command and had a small skirmish with him in which there was not much loss on either side. The Rebs retreated over the Hatch River in the direction of Jackson, Tennessee. They burnt the bridge over the river, thus stopping us from following them. It was the intention to rebuild the bridge & follow them, but on sending some scouts to Jackson, it was found that they had evacuated that place also…

… After going nearly to Ripley, Mississippi and seeing no signs of any Rebs, and getting very short of rations, it was finally concluded to give up the expedition and return to Memphis. We arrived here on night before last after an absence of ten days, during that time we marched 120 miles on foot and went 68 by railroad. I thought I had seen hard soldiering before this, but never in my life did I see as hard times as on this march. The weather was uncommonly hot, the roads dusty, and a good part of the time we were on very short rations. Many times we would not stop at night until near midnight & then be called up to match at 3 o’clock in the morning. We hardly ever had time to cook breakfast, and at night we would be too tired to get any supper. But notwithstanding all the hardships, we passed through. My health was good all the time, but my feet got very sore.”

In addition to the military presence in Memphis, there were also economic controls put in place in order to prevent union goods being used to aid Confederate forces. In a letter written on May 14, 1864, Joseph Maitland expressed his support for these measures.

“On day after tomorrow the lines close round the City of Memphis and no more goods or citizens will be allowed to pass out. Heretofore, citizens coming in from the country would take out goods to the amount of 800 & 1,000 dollars at a time and we have good reasons to believe that a good portion went to Forrest’s Army. But that game will be blocked for the next hundred days to come.”

Joseph Maitland Takes Ill

On August 7, 1864, Joseph Maitland wrote to Arabella with some unfortunate news about his health.

“Again I seat myself to pen you a line. I suppose you will think strange of my being in our old camp while our Regiment is out with the expedition. It certainly is strange, but if you give me time enough, I will give you the reasons. When I wrote you last we were at La Grange expecting orders to march every moment. In the afternoon of the day I wrote, we received orders to march and accordingly we took up our line of march to Davis’ Mills where we encamped for the night and over Sunday. On Monday we started again taking a southerly direction, marched about 15 miles to a creek by the name of Coldwater. During the night we were there, it rained & I got pretty thoroughly soaked. The next day I felt very badly with toothache & headache but managed to march with the regiment to Holly Springs where we went into camp.

Soon after stopping, I was taken with a chill & afterwards high fever and was unable to do anything. After remaining there two days & not getting any better, I was (with a number of others out of the Brigade) ordered to go back to Memphis to report to the Superintendent of Hospitals for treatment. On the evening of the 3rd, we started & arrived here on the 4th & reported. A good many were sent to hospitals but as I always had a peculiar dread for the institution, I persuaded the surgeon to let me come out to our old camp. I am not to say dangerously ill as I have got the fever about broken up. I still have very severe pain in my side & head, but hope to be better in a few days. I think the most I need is rest as we have had none scarcely tis summer.”

While recovering from his sickness, Joseph Maitland also wrote about the deteriorating economic situation in the area in a letter dated August 13, 1864.

“The only way we can hold our own with the women peddlers is to milk their cows that come round our camp. Yesterday I was having very good luck milking, when the owner of the cow—an old woman—came running out and you had better believe I caught it. She said, “Don’t you feel ashamed to milk other people’s cows?” I told her no, I didn’t feel at all bad when they sold us milk that was half water. She got very huffy & went to drive her cow off but as she was not at all afraid of soldiers, she ran up to our camp & I finished milking her right before the old woman’s eyes and you had better believe she cared. But I didn’t mind her & so got milk enough of our coffee for several meals (don’t think I am getting demoralized).

There has been an order issued stopping all goods except those sold by the sutlers & government stores from coming down the [Mississippi] River. The consequence is that the merchants in Memphis have raised on their prices more than double what they used to be. For instance, suspenders that used to sell for 50 cents are sold for $1.50. Very common woolen shirts sell at $10 & $12 per pair. But perhaps this is not interesting to you & so I will say no more on this subject.”

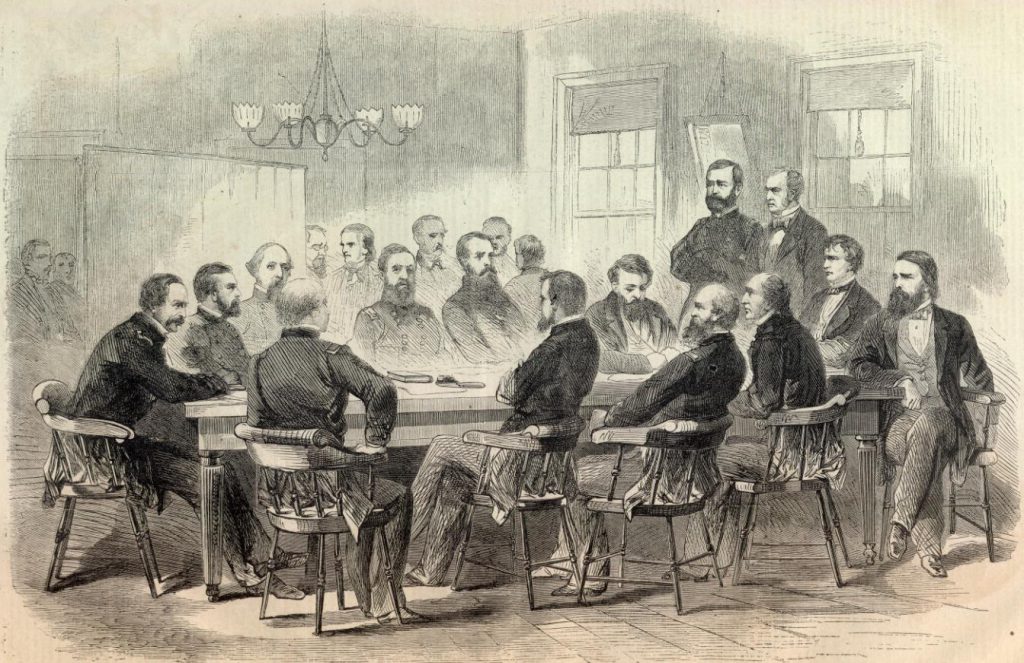

Joseph Maitland Court Martial Clerk

By October, 1864, Joseph Maitland had been detailed as a clerk for the General Courts Martial being held in Memphis, Tennessee. He seemed to enjoy the duty as he wrote to Arabella on October 23, 1864.

“I am still clerking for the Court Marshal and am having first rate times. I am enjoying very good health for which I feel durably thankful.”

He continued working as a clerk for at least another month before being ordered back to his regiment along with all the other detached men from his division. Joseph Maitland informed Arabella of the situation in a letter written on November 17.

“In my last I told you that Orders had been received here that all the detachments and detached men belonging to the 1st & 3rd Divisions, 16th Army Corps were ordered to Paducah, Kentucky. Yesterday the detachment of our brigade broke up camp and last evening started up the [Mississippi] River. The weather here for the past four or five days has been very wet and disagreeable — one of the very worst times to break up camp. But notwithstanding all the disadvantages, the Order had to be obeyed. I did not get started with the detachment as there was still considerable business of the Court on hand. There was an application signed by all the members of the Court sent to Head Quarters requesting to have me permanently detailed. Today the application came back disapproved so I am looking all the time to be relieved and ordered to Paducah. I may not get off for a few days yet — perhaps not till next week some time. I was in good hopes that I would get to remain here as I am so comfortably situated but it seems to be my lot to have to go & I will submit although it goes considerably against the grain.”

Despite Joseph Maitland believing he was soon to return to his regiment, the court martial to which he was serving was only dissolved in December, 1864, as he detailed in a letter written on December 16, 1864.

“Since Gen’l [Napoleon J. T.] Dana assumed command of this department, he has made a good many changes. Our Court Martial has been busted up. The Headquarters District of Memphis has been changed to Headquarters Post and Defenses of Memphis. Gen’l Buckland still in command. Gen’l [James Clifford] Veatch takes command of the District of West Tennessee. The whole including Paducah and the country to Vicksburg including Vicksburg under command of Gen’l Dana.”

Joseph Maitland was mustered out on May 31, 1865. He married Arabella Wharton in 1867 and died in 1918.

We’d like to give a special thank you to William Griffing of Spared & Shared for his work in transcribing and sharing these letters.

To read more of Joseph Maitland’s letters, numerous letters written to him by friends as family, as well as access thousands of other Civil War letters and documents, sign up for a Research Arsenal membership.

If you enjoyed this article, check out some of our other featured collections like Henry Cole Smith of the 8th Connecticut Infantry and William Prince of the Ordnance Department.