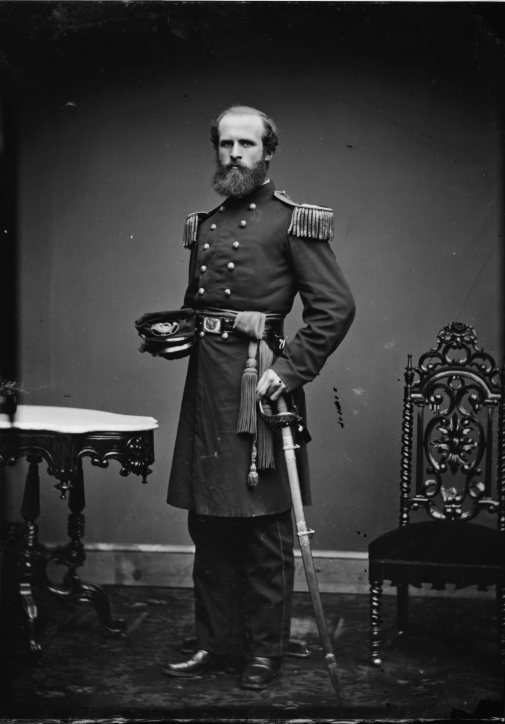

Research Arsenal Spotlight 5: Albert Henry Bancroft of the 85th New York Infantry

Albert Henry Bancroft was one of five children born to shoemaker Jenson Bancroft and his wife Esther Susannah Batchelor in Ontario County, New York. Bancroft enlisted in the 85th New York Infantry on September 26, 1861, as a private in company B. He would later receive a promotion to corporal.

Our collection contains 62 letters, mostly written by Albert Henry Bancroft to his family, with a few other letters being written by his brother, William, who served in the 24th New York Cavalry, and a few by sister, Almira “Myra” Bancroft. The letters span from 1861 until his capture in 1864.

85th New York Infantry duty in Washington, D.C.

After its formation, the 85th New York Infantry was sent to do duty as part of the defenses of Washington, D.C. In a letter from January 14, 1862, Albert Henry Bancroft related an amusing story about his company’s somewhat unusual taste for meat:

“There was one or two companies out practicing with blanks and the train of mule teams — 6 mules in each team — come along and not liking the noise, they pricked up their ears and took French leave as though they were sent for and the way they went was not slow. One mule capsized and went under the wagon and all stopped and we thought we were going to have some fresh mule for supper but we were doomed to be disappointed for when the wagon was raised off from him, he was as good as new and the last I saw of him he was going along in his mule way rejoicing. But we all hoped him dead. We have eat so much mule beef that our ears are about 3 inches long and thrifty indeed. I am almost ashamed to look a mule in the face, and some of the boys are braying quite lustily, and all are tough and so am I.”

In a letter to his aunt on March 2, 1862, Albert Henry Bancroft conveyed his rather unflattering opinion of the city of Washington:

“ The inside of the building is mostly marble and of all kinds and colors and it does not seem as though the hand of man were capable of working out such wonders. One may travel all day and yet see something new at every turn, and here inside the walls of marble, it seems we are keeping our drones or fast men. We had better take the bees way of ridding the hive of its worthless members and hang them and then they would not be picking quarrels and the stand behind the fence ready to join the biggest heap and share their profits and cry, “didn’t we give it to ’em.” But the Capitol is all that makes Washington for there are more poor, rickety old houses and three-cent grog shops here than there ought to be in seven cities and anyone that visits the city must have a keen eye to get his money’s worth.”

Shortly after this letter was written, the 85th New York Infantry left Washington D.C.

Albert Henry Bancroft and the Battle of Seven Pines

The Battle of Seven Pines occurred on May 31 and June 1, 1862. At the time, it was one of the the biggest battles of the Civil War to date and resulted in large casualties to both the Union and Confederate armies with neither side winning a decisive victory. In a letter to his sister written a few days after the battle on June 6, 1862, Albert Henry Bancroft wrote in great detail about his regiment’s role in the battle:

“The first indication we had of the enemy was a cannon ball—and then another, sounding more like a swarm of bees in a great hurry but doing no harm. This was about 11 in the forenoon. And then the order was to fall into line for the Rebs were driving in our pickets (which they had done the day before) and in five minutes our Brigade was in line and the 81st New York and 98th were sent out to support the pickets. They marched into a piece of woods which our men have been felling to prevent them from coming on to us and we were put in to the half-finished rifle pits for them to fall back on in case they were driven back. The 92nd [New York] was to the right of us and between us was a small fort with three small cannons inside and three out. We were in the pits nearly an hour before we saw anything of the enemy. In the meantime, those in front of us were hammering away at them and the little Brass Boys were speaking to them once in awhile but their balls had been kept too long and broke all to pieces when they got over into the woods. But soon we saw what was to pay. Those in front came running back beyond us and the obnoxious Rebel flag was seen bearing down upon us through the slashing when the Colonel said, “Take good aim boys, and let them have it,” and for the first time we drawed a bead on the Rebs and then they were more than 50 rods [275 yards] off, but they felt it. We loaded and fired as fast as possible and the canister shot was poured into them from the cannon but they still bore down upon us until within about 20 rods [100 yards] when what there was left of them turned and went back. But there was not one-fifth of them able to get back out of the two regiments that started out.

But there was fresh troops ready to take their places and we saw that they were coming down on us on both sides and in the center and that the cannons were deserted and the horses nearly all killed and wounded and floundering in their harness. Our Lieutenant Colonel [Abijah J. Wellman] was wounded and the Colonel [Jonathan S. Belknap] no where to be seen and the Major [Reuben V. King] also had got out of the way or somewhere else and the regiment gave away for a moment. When remembering that we had no orders for doing so, we rallied into the pits again and with a shout of defiance we poured in the leaden storm, doing fearful execution, but they swarmed on all sides and we had to run or be taken prisoners. We fell back across our camps and there met reinforcements and from that time until dark, we were fighting anywhere we could see Rebs. But there was a fault somewhere. If Couch’s Division had supported our left as he should, we never need to have been driven from our camp and lost everything. But the battle is over. Our dead are buried. Our wounded are cared for. The enemy are driven beyond our camps and we can draw any signal from it we see fit. But it was a bloody field.”

Albert Henry Bancroft gave an additional account of the battle in another letter written on June 25 presenting many of the same details.

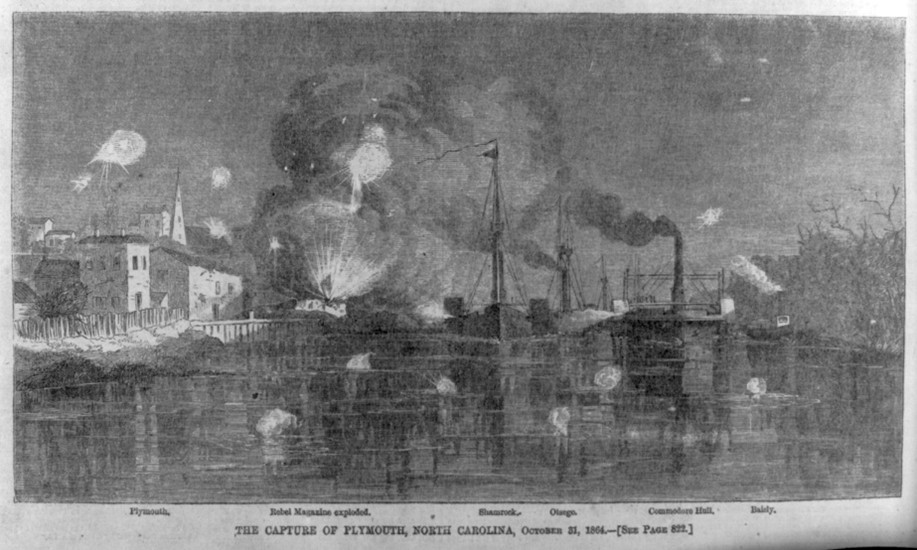

The 85th New York Infantry at Plymouth, N.C.

In May 1863, Albert Henry Bancroft and the 85th New York Infantry moved to Plymouth, North Carolina where they would serve for a large portion of the war. Writing to his sister, Albert Henry Bancroft described their new location:

“We are all well and over head and ears in work digging, chopping, and picket duty. Our brigade is all the troops that are here and the duty will be heavy for awhile until the place is fortified. Plymouth has been a nice place for a small one but the best buildings are burned and some of the brick buildings pierced for rifles which makes the place look military. The streets are all lined with shade trees and soldiers quarters where the elite once lived. We are outside of the town in new tents raised with boards 4 feet high—4 in each tent. We have brick walks in front of the tents, one walk right in front and one the whole length so [sketch of parallel lines I I I I I I] and the corners are sodded over and all say they look nice. So you see we are comfortable.”

In April, 1864, Confederate forces led a successful attack on Plymouth, driving back the Union forces and leading to the surrender of the garrison at Fort Williams. Albert Henry Bancroft was among the soldiers captured on April 20, 1864 and was held at Andersonville Prison until his death in August 1864.

We’d like to extend a special thanks to William Griffing of Spared & Shared for his tireless work in transcribing and sharing these documents. You can read the full collection of letters and thousands more with a Research Arsenal membership.

Check out more of our spotlights like this one on Colonel Clark Swett Edwards of the 5th Maine Infantry and John L. Hebron of the 2nd Ohio Infantry.