Research Arsenal Spotlight 29: Albert Jenkins Barnard 116th New York Infantry

Albert Jenkins Barnard was born in 1841 to Albert Barnard and Elizabeth Atwater (Jenkins) Barnard of Buffalo, New York. His father died in 1849, and he had one brother, Lewis, who he mentions frequently in his letters.

On August 13, 1862, Albert Jenkins Barnard enlisted in the 116th New York Infantry as was mustered in as captain of company B.

Albert Jenkins Barnard and the Lieutenants of Company B

After taking command of his company, Albert Jenkins Barnard found himself dissatisfied with both lieutenants under his command. The first hint of trouble showed in a letter he wrote to his brother, Lewis, advising him not to enlist unless he could be an officer.

“I don’t think much of my lieutenants and think they will soon be ousted. Let me say here, don’t enlist as a private on any account. Do not accept any position lower than Orderly [Sergeant]. Camp duty is mighty hard, although we have some nice times. You ought not to accept a position lower than 2nd Lieutenant.”

On September 22, 1862, Albert Jenkins Barnard wrote to his mother about the situation, including some positive words about their Colonel, Edward Payson Chapin.

“We all like Col. Chapin very much. He is a much better officer than we supposed. He gives his orders splendidly and handles his men like a veteran. Major Love—he too is a bully officer. We have got a fine regiment and very few poor officers. But they won’t be permitted to stay long. Two of them, I regret to say, are in Co. B. I guess they will both have to leave this week. Willis, the 1st Lt. is a disagreeable fellow. The men don’t like him at all and he can’t learn military. When I returned from Baltimore Saturday, he was drilling the company. As soon as they saw me, they gave me three cheers. Corbett (the 2nd Lt.) is a very clever, good sort of a countryman, but he can’t drill and never can learn. I feel very sorry for him. The Colonel says I shall have John Dobbins just as soon as he can arrange matters.”

In October, 1862, things came to a head and both First Lieutenant Leander Willis and Second Lieutenant Daniel Corbett were replaced. In the case of Leander Willis, he faced rather serious accusations which forced his resignation, as Albert Jenkins Barnard detailed in a letter written on October 4, 1862.

“I have really been very busy of late; more so the last week on account of having no Lieutenants. Yes, Corbitt (my 2nd) resigned last Monday. Col. Chapin advised it as it was clear enough to us all that he could never make an officer, that the men wouldn’t have any confidence in. Willis is a scamp, and had his choice to resign or be disgraced. About three weeks ago he borrowed my muster roll and carried it to Washington where, through a sharper, he laid claims against the government for about one thousand dollars. He claimed that he had spent about that much for board for the men, from the time they went to Camp Morgan to live; which is all a humbug. The boys are all from the country and lived at home till they went to camp. When Mr. Willis returned from Washington the Colonel sent for him and told him that he knew all about his performances, and that his resignation would be accepted, and the soon he sent it in the better. So in it went and out he went. They, the Lieutenants, are still in camp. Corbitt will probably be appointed postmaster or something else but Willis will have to skedaddle.”

The “Little Captain”

After sorting out his junior officers, the next task that consumed Albert Jenkins Barnard was making sense of the expenses that occurred while the company was first being formed. On the first muster roll of the 116th New York Infantry, the captain of company B was given as Joseph E. Ewell, however he seems to have left shortly after the regiment was formed and Albert Jenkins Barnard had his suspicions that Ewell never seriously intended to stay on as captain.

“A captain is responsible for all company property; we all have to take receipts from the men for everything that they draw. The receipts for this company were given to the Quarter Master so all I have to go by is the word of the men. However, I have got the men to sign the clothing book as I am all sound there. I expect to be out something but cannot tell how much. Most of the captains are out from forty to sixty dollars worth but mine won’t be near that. I think if Capt. Ewell had really intended going with his company, he would not have let things run at odds and ends as they did. This I found out after I got here and have had to straighten out myself. He did not take a single receipt that he delivered. Now don’t let this bother you for I am all right now and am much better off than most of the captains.”

Albert Jenkins Barnard was also concerned with making sure his men drilled well and maintained a clean appearance. Despite his strict nature when it came to discipline, he also managed to acquire the nickname “the little captain,” which the men all found very amusing. He detailed the story as well as his duties to his mother in a letter written October 26, 1862.

“John Dobbins and I still run the company alone as my first lieutenant has not arrived yet though I expect him every day now and we run it “bull,” as you may know from what the Colonel told Dr. [C. B.] Hutchins the other day after dress parade. He said, “Co. B is the best in my regiment” and the “little captain is a brick.” I am known here as the little captain and now I will tell you why. While I was messing with Lt. Jones and others one day, I was late to dinner and Jones told his servant—a little Dutch boy—to run and tell Capt. Barnard that dinner was getting cold. He stopped a minute and then said, “de cline capting?” which is, if pronounced as spelled here, the little captain. The boys all think it is a good joke and so that is my name. But nevertheless, my company can beat all others in the regiment in drill and appearance; on drill and dress parade. I punish all who appear without clean brasses and bright shoes by putting them on guard. At first I had a great many, but now scarcely ever have one.”

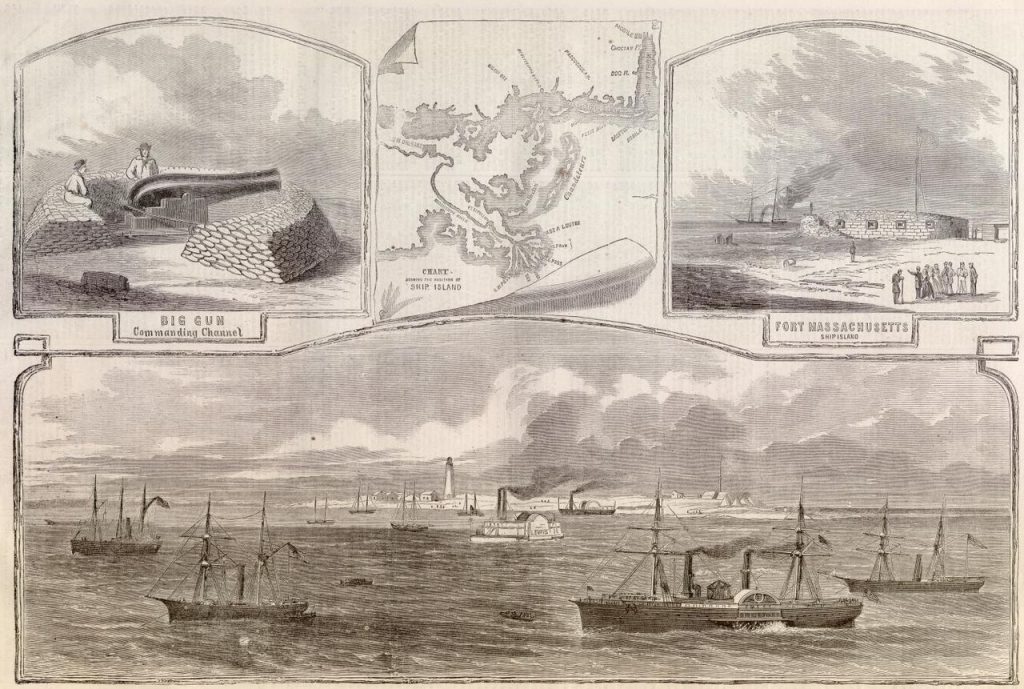

The 116th New York Infantry at Ship Island

In December, 1862, the 116th New York Infantry set out for Ship Island, Mississippi. The voyage was long and stormy, and Albert Jenkins Barnard wrote a detailed account of it in a letter to his mother on December 14, 1862.

“After ten days sail, we find ourselves at Ship Island and ordered to New Orleans. On Thursday the 4th, we pulled up our anchor and started out to sea. When off Cape Henry (1 p.m.), we stopped till the rest of the fleet came out which was about 9 in the evening. We then all started together in two lines, seven ships in each line—the Baltic leading one, and we the other.

We kept together till the following noon when the wind commenced blowing and three dropped out and ran close to shore. About this time there were a great many sick aboard the ship. The wind kept increasing till midnight and I tell you what, it was a grand sight. The moon shone bright and the waves somewhat high. It was impossible to stand anywhere without holding on to something. From the deck, it looked as if ever time our bow went down that it was going under, but when the wave came she would rise again and part it and send the spray all over the ship. And once in awhile, a wave would roll clear over the paddle boxes. Perhaps you will have some idea of the force of the wind when I saw that it would take the tops off the waves and blow the water as it does the dust from the dirt piles in our streets.”

On December 21, 1862, Albert Jenkins Barnard wrote another letter, this time detailing the island itself.

“We get along very nicely although this is such a sandy, wild place. There is nothing but sand for four miles. Then there is a swamp that reaches nearly from shore to shore and in the swamp Alligators and a species of palm tree. Further on is a sort of prairie covered with tall rushes which are so long that they will reach a man’s knees when riding on horseback. About six miles from here is a beautiful little lake in which are plenty of fish and lots of ducks. We are having a better time here than I supposed we would. We have been living on oranges and oysters since we came here.”

While on Ship Island, the 116th New York Infantry celebrated Christmas in a rather unique way by having senior officers and the non-commissioned officers and privates change roles for the day. Albert Jenkins wrote about the day in a letter written on January 2, 1863 after the regiment had moved to Greenville, Louisiana.

“Christmas Day the command was turned over the non-commissioned officers and privates. Christmas Eve the companies held their elections for Captain &c. and then the officers so chosen deleted the field officers. Sergt. John Rohan of Co. D was the Colonel, a boy from Co. A the Lt. Colonel, and one of the color corporals was Major. These officers were to do the best they could and they did first rate. Went through with guard mounting and dress parade without making a mistake.

John Higgins was detailed as corporal of the first relief and I corporal of the 3rd. Most of the others had to stand guard. Some of the men would run the guard and then the officer in command would send me with a guard to arrest them. They kept us running, I tell you. They had most of the officers in the guard house. It was a very warm day. Those not on duty were around without their coats.”

Albert Jenkins Barnard was discharged on July 29, 1863 after being promoted to lieutenant colonel but never being mustered as such. After the war he married Clara Sizer, who was the sister of William Sizer who was frequently mentioned in his letters. Albert Jenkins Barnard died on January 10, 1916 at the age of 74.

To read the full collection of letters by Albert Jenkins Barnard and access thousands of other Civil War letters and documents, sign up for a Research Arsenal membership.

We’d like to give a special thanks to William Griffing of Spared & Shared for his work in transcribing and sharing these letters.

If you enjoyed this article, check out some of our other featured collections like Jacob Claar of the 138th Pennsylvania Infantry and William Fish of the 11th New Hampshire Infantry.