Research Arsenal Spotlight 38: Amasa Hammond 3rd Rhode Island Heavy Artillery

Amasa Hammond was born in Rhode Island in 1846. At the age of 16, he enlisted in the 3rd Rhode Island Heavy Artillery as private in Company K. Because of his youth, Amasa Hammond wrote letters with a more forthright and plainspoken nature than many of the other letters we’ve previously featured in our spotlights. The letters in this collection were all written to Amasa Hammond’s friend, James Coman, which is another reason for the tone of the letters. Amasa Hammond’s letters also illustrate the sometimes difficult relations between soldiers fighting in the war and those left at home hundreds of miles away.

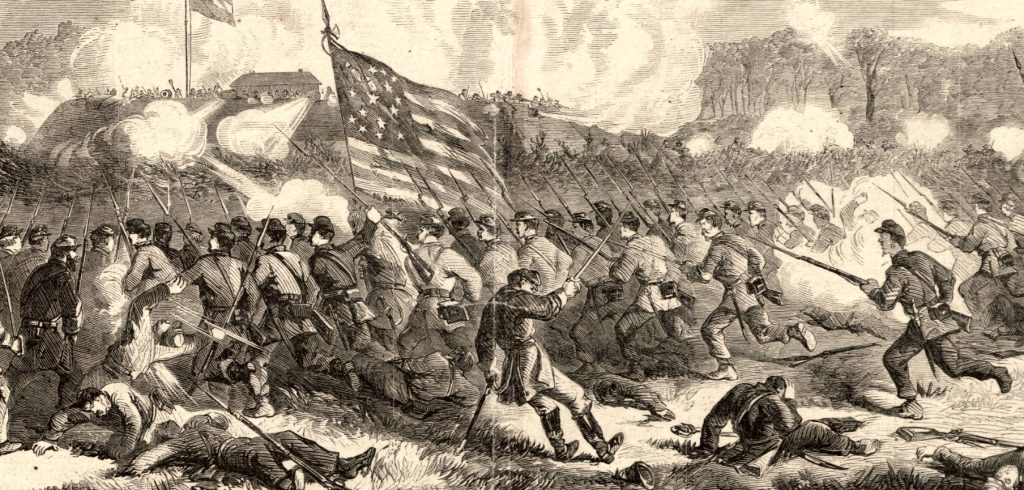

The Battle of Secessionville

Amasa Hammond wrote his first letter in this collection on June 18, 1862, shortly after the Battle of Secessionville (also sometimes called the first battle of James Island). At the time Amasa Hammond was sharing a tent with Edward Steere, Henry M. Smith, and some others. Partway through his letter, Amasa was interrupted by Edward Steere who wanted to add some of his own words as well. The second sentence in the quote below was started by Amasa Hammond and then finished by Edward Steere (italics). Some of Edward Steere’s additional comments unrelated to the battle have been removed and the description concludes with Amasa Hammond’s words again.

“I now take my pen to let you know that I am well after returning from the battlefield [of Secessionville] and so did all the rest of the boys. […] It was a horrible sight to see so many young fellows with their legs mangled in every form….

…So now I will finish. Edward came in just as I was writing about the wounded. Some had their hands off, some had their arms off, some with their head shot half off. Lieutenant [Isaac M.] Potter was wounded in the hand. We could not take the place because we didn’t have men enough but we have sent for twenty-five thousand men and a siege train and then we are going to try them again.”

In fact, there was no second attempt at taking Charleston by land, but there was still fighting ahead for the 3rd Rhode Island Heavy Artillery. In August, 1862, Amasa Hammond’s thoughts on the war had already turned grim though he still believed the Union would prevail.

“There ain’t much sight of settling this rebellion. The secesh is tough and hang like bulldogs but General Burnside will come at them when they don’t think of it and [k]nock them in a cock[ed] hat.”

Trouble at Home for Amasa Hammond

A frequent topic in the letters Amasa Hammond wrote is the strained relationship between him and his father. He was especially leery of a woman named “Paige” whom his father was spending a great deal of time with. It seems likely that his parents were either divorced or separated, because he also mentioned writing to his mother once. Paige never appears in a census living with Amasa’s father, William Hammond, so the relationship seems to have ended sometime before 1870.

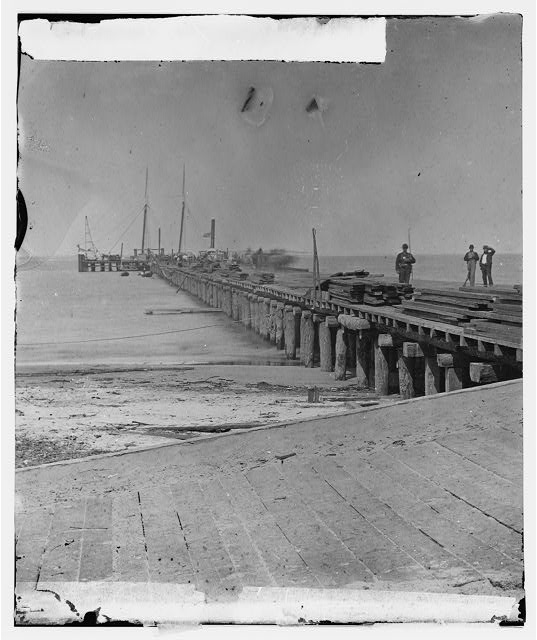

In a letter written from Hilton Head, South Carolina on October 3, 1862, Amasa Hammond made his feelings about Paige very clear.

“I now take my pen to let you know how I get along. I am well as usual. I have written several times to you and my other friends but I ain’t had a letter from home but once since I received my box. But I don’t care a damn whether they write or not. I have got a place to send my money and it will be safe. But when folks can’t send me so much as a paper or a box, I don’t care a damn. I know what makes the things so unpleasant — ’tis that long legged Paige. James, I am plain-hearted. I just as like you you would read this letter to her as not and rather you would…

…James I want you to write soon and tell me what that damn gap mouth Paige said to this letter. I want my father to take that money that I sent home and get as drunk as he can before he lets her have any of it.”

A few days later, Amasa Hammond wrote again, revealing that he knew his father was trying to keep his relationship with Paige a secret from him.

“James, I want you to tell me what the reason why my father don’t write. Does he think because I am ten or twelve hundred miles off he thinks that I don’t hear what he is doing. I hear from Rhode Island.”

The Second Battle of Pocotaligo

In October, 1862, Amasa Hammond and the 3rd Rhode Island Heavy Artillery encountered another hard fight at the Second Battle of Pocotaligo. The Union army had hoped to further isolate Charleston, South Carolina by cutting off Charleston and Savannah Railroad, but Confederate forces managed to hold them off and they were forced to withdraw. Amasa Hammond described it as the second fight his company (K) took part in.

“It seems that you heard that we had a fight and you didn’t hear no lie. I saw the fighting but didn’t get in to it. Just as we got on the battlefield, the rebels got reinforced so fast that we had to retreat under the fire of the gunboats. It was the hardest sight that ever I saw except [at] James Island. The dead and wounded laid along for eight miles. We gathered up what we could of the wounded and carried them on board the boats and sent them to Hilton Head Hospital. That was the second fight for Co. K to be at.”

One of Amasa Hammond’s tentmates, Henry M. Smith wrote a letter at about the same time as Amasa. In it he asked their mutual friend, Jim, “What do the folks think about this damn shittin’ war around there? I think it is about played out. I wish I was at home.”

Amasa Hammond served in the 3rd Rhode Island Heavy Artillery until he mustered out at the end of the war on July 20, 1865. Several letters written by Edward N. Steere are also available at the Research Arsenal. You can read all of these letters and access thousands of other Civil War letters and documents with a Research Arsenal membership.

We’d like to give a special thanks to William Griffing of Spared & Shared for transcribing and sharing these letters.

If you enjoyed this article, check out some of our other featured collections like Richard Weld of the 44th Massachusetts Infantry and David McGowan of the 47th Illinois Infantry.