Research Arsenal Spotlight 16: Andrew Jackson Clark of the 23rd Massachusetts Infantry

Andrew Jackson Clark was born in 1837 to Melzar Wentworth Clark and Sabina Hobart (Lincoln) Clark of Hingham, Massachusetts. Before the Civil War, Andrew Jackson Clark worked as a painter and was a volunteer fireman. He first served in the Lincoln Light Infantry (also known as Company I of the 14th Massachusetts) at the outbreak of the war for three months. He then served in Company H of the 23rd Massachusetts Infantry and during that service composed the twenty-eight letters in our Research Arsenal collection.

Andrew Jackson Clark first enrolled in the 23rd Massachusetts Infantry on October 9, 1861. His letters in this collection begin on December 13, 1861 while in Annapolis, Maryland and mostly pertain to matters at home as he waits for his regiment to be sent out. In a letter from December 14, 1861, he gave a brief account of his camp and the vicinity:

“On our extreme is the camp of the D’Epineuil Zouaves. Nearly opposite is the 51st Pennsylvania which is trimmed up with arches and festoons of evergreens & flags, & looks like a vast amphitheater arranged for some great holiday. On the left are the camps of the 25th & 27th Mass., & the 8th & 16th Conn., all trimmed in truly [royal] style. Then while guard mounting or on dress parade on their numerous parade grounds with the bands a playing, the scene is truly beautiful—especially in the eyes of a soldier.”

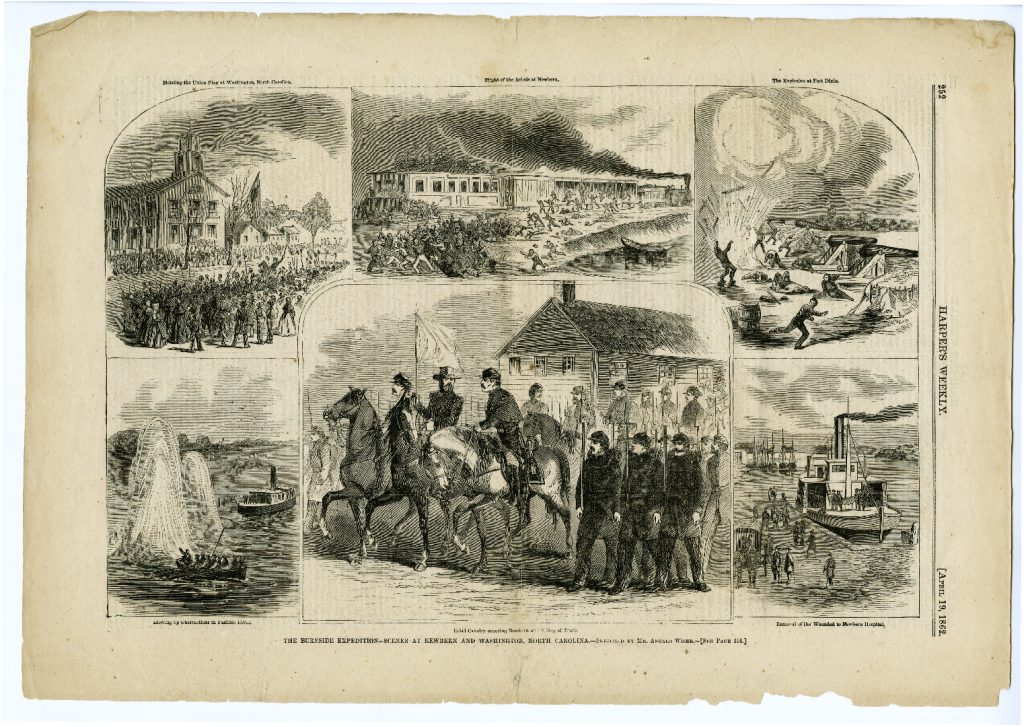

The 23rd Massachusetts Infantry and New Bern, North Carolina

By June, 1862, the 23rd Massachusetts had been assigned to provost duty in the city of New Bern, North Carolina. On July 27, 1862, Andrew Jackson Clark wrote home to his sister Ada about an incident of their regiment being fired on while acting as guards in the city and their manner of revenge:

“The monotony of the past few weeks has been somewhat disturbed within the past few days. Some fiends in human flesh have under cover of dark & stormy nights taken the advantage & fired upon several of our sentries which are stationed on the corners of the streets in different parts of the city. Double guards were posted & every attempt was made to ferret out the villains who perpetrated these diabolical acts. On Thursday night the guard on post [ ] of the 3rd District was fired upon & an arrest was made in the following manner. The guard was posted as usual while a second sentry [hid] himself and his arms in the vicinity. In this way he surprised & arrested a person who was prowling around there. A pistol & a large dirk knife was found upon his person. On Friday night the guard [Michael A. Galvin] on Post 5, 3rd District, was fired upon and shot through the fleshy part of his thigh (he belongs to Co. C of Glocester). Col. Kurtz instantly turned out the whole guard and went up there & arrested seven persons that night. A negro who was secreted nearby saw the flash of the gun which proceeded from the door of a large two-story house opposite.

The next morning without giving them any previous warning, the whole regiment armed with arms, axes, ropes, &c. marched up there & surrounded the house, placed everything in it out in the street, turned out the women & children & then commenced the work of destruction of all the property on the place. They leveled the house with several others which were connected with it, tore down the fences and out buildings, cut down the fruit trees, destroyed the products of a nice kitchen garden, leveled a splendid field of corn, and in fact, destroyed everything of value belonging to the estate. It was some fun for the boys maddened by the numerous attempts at their lives. The regiment went in with a will and worked like tigers until everything lay in ruins. A large crowd of citizens & soldiers were present & saw the just chastisement administered. It was not severe enough for the men—or fiends, for they do not deserve the name of men who will thus attempt to murder & assassinate the guards who are stationed about this city for the sole protection of the citizens & their property. They deserve to be hung at the nearest lamp post & should they be caught in the act, they will not meet with a much better fall to further their infernal designs. The street gas lights have several times been extinguished. A small field piece now sits half loaded in front of the guard house & should they attempt it again, they will get blowed to where they belong with little warning.”

In the same letter, Andrew Jackson Clark provided an update of the incident written on July 29:

“Since writing the above, I learn that the fiend who fired upon & shot the sentry was arrested Sunday morning & thrown into jail. He will have a trial & probably he may be hung. A thorough search has been made & arms of all description have been found secreted in different parts of the town consisting mostly of rifles, double & single barreled muskets, &c., besides powder & balls. Most of them were loaded. A splendid rifle & a double-barreled gun was found in the house from where the shot was fired Friday night. Both were loaded. There has been no more firing since then.”

Andrew Jackson Clark reflects on recruitment and the treatment of soldiers

In a letter from September 14, 1862, Andrew Jackson Clark wrote to his brother, George Clark, some of his thoughts about the government’s various bounties and incentives to get more men to enlist in the army. While he understood the need for more soldiers quite clearly, the poor treatment of soldiers whenever they returned home during furloughs, and the government’s methods to prevent desertion during that time, left a sour taste in his mouth:

“I don’t know what to make of this government & the people at this time. They offer every inducement to men to enlist, paying them exorbitant prices as bounty money & getting a better class (as the paper says) for their money. Yet they treat the men who have stood the brunt of a year & a half’s campaign like criminals or worse. Should a soldier from the hardships he has had to endure get sick, broken down and perhaps discouraged, get a furlough from his surgeon and goes home to recruit his exhausted strength, the minute he steps his foot in Northern soil a price is set upon his head, hunt him down [and is told] he has no business here—send him back to face the rebel bullets without one word of consolation from his friends. Should they live in a neighboring town & he should attempt to visit them, the police will be put upon his back & he will be arrested like a common felon. Some sneaking coward will give them the wink & get five dollars for his trouble should he be taken prisoner & let off on his parole. He must be confined—yes, held a prisoner by our own government far from the friends he has earned a right to see, whose benignant smiles & tender care he needs to refit him for active service. Oh, consistency, thou art a jewel. I have long wished to speak of these things & call them to the mind of the people in their true light but I find I am inadequate to the task.

It would break the patriotism of a man whose love of country was as strong & unbending as steel itself to see the harm of all the things heaped upon the poor soldiers of the army of the Union. Did I not know I was doing my duty, not to individuals but to my country so far as lies in m power, humble though it may be. Did I not believe that we are right & through the mercy of God will triumph over our enemies who seek to tear down as fair a government as ever existed (& if it is right conducted can do a great deal of good to suffering humanity), I should grow sick at heart & despair of any good coming out of this sinful world. I should wish myself dead before I had enlisted in the U. S. service. But I will say no more. I do not dare to write the truth as it exists. Suffice it that as long as I retain my health & strength, I shall struggle against the enemies of my country wherever they exist until this rebellion is ended. Should I be called upon to sacrifice my life in her defense, I shall die knowing that I have done my whole duty.”

Return of Andrew Jackson Clark and the 23rd Massachusetts Infantry

Though he battled some sickness throughout his service and toward the end of his term was working at a nurse at the US General Hospital in Hampton, Virginia, Andrew Jackson Clark remained healthy enough to serve out his original three year term and be discharged with the rest of the members of the 23rd Massachusetts Infantry that did not reenlist. On their way home, they faced a delay due to an outbreak of yellow fever in New Bern which forced their ship to be quarantined off of Fortress Monroe. In a letter dated September 30, 1864, Andrew Jackson Clark wrote to his brother about the delay:

“I expected to answer your letter in person but am prevented from doing so by an unforeseen delay. Here we are on our way home after an absence of three years delayed for ten days why what, you will ask. Why we are in quarantine. Have we got the yellow fever on board? Not a bit of it but it is in Newbern, therefore every vessel hailing from the woebegone place is ordered in quarantine.

The regiment has not been in Newbern and most of it not within ten miles of there. Had we come five days sooner (which but for the want of a little spunk in our officers we might have done) or had we come by the way of Beaufort, North Carolina, or had not taken any citizens aboard, we might have passed all right. But as it is, I don’t see but we have got to stop here on a crowded transport with constant exposure of the men to bad air, wet dampness, &c. which is enough to bring on the fever if nothing more. Here we have to get to lie for 8 days longer. Possibly we may get off before that time as every exertion is being made to that effect. At any rate to be put ashore somewhere where we will be alright. To make the matter worse, a man belonging to Co. F died last night of consumption and his body still lays in the long boat alongside because no one can go ashore until someone comes out to us.”

When the quarantine ended, Andrew Jackson Clark mustered out of the 23rd Massachusetts Infantry on October 13, 1864. He returned to civilian life in Massachusetts and in 1869 married Evelina M. Caine. He passed away in 1927.

We’d like to give a special thanks to William Griffing of Spared & Shared for his work in sharing and transcribing these letters.

If you’d like to read more of Andrew Jackson Clark’s letters, as well as thousands of other Civil War letters, sign up for a Research Arsenal membership.

You can also check out some of our other recently featured collections, like David Walker Beatty of the 63rd Pennsylvania Infantry and Alfred Homer Johnson of the 30th Georgia Infantry.