Angry Archivist: Can I Just Glue It?

For this post blog post, I’m deviating a bit from the Civil War and shifting gears into archival madness that I sometimes run across on a personal level. I feel that although we’re not discussing Civil War archives, this is something that very much applies to them, or any personal family documents and art you may have framed. Specifically, today we’re talking about glue, and why it should never be anywhere in the same place as documents, photos or artwork. So, in answer to the question, “Can I just glue it?” No, please don’t.

First, a little backstory. As you may have guessed, I’m a bit of a history nerd, and that love of history extends beyond the Civil War to collecting ancient Egyptian artwork ever since I was a little kid. Imagine my excitement to find a whole slew of hand painted souvenir papyrus at a garage sale recently for $30! I snatched them all up and took them home to reframe them, and then I got angry.

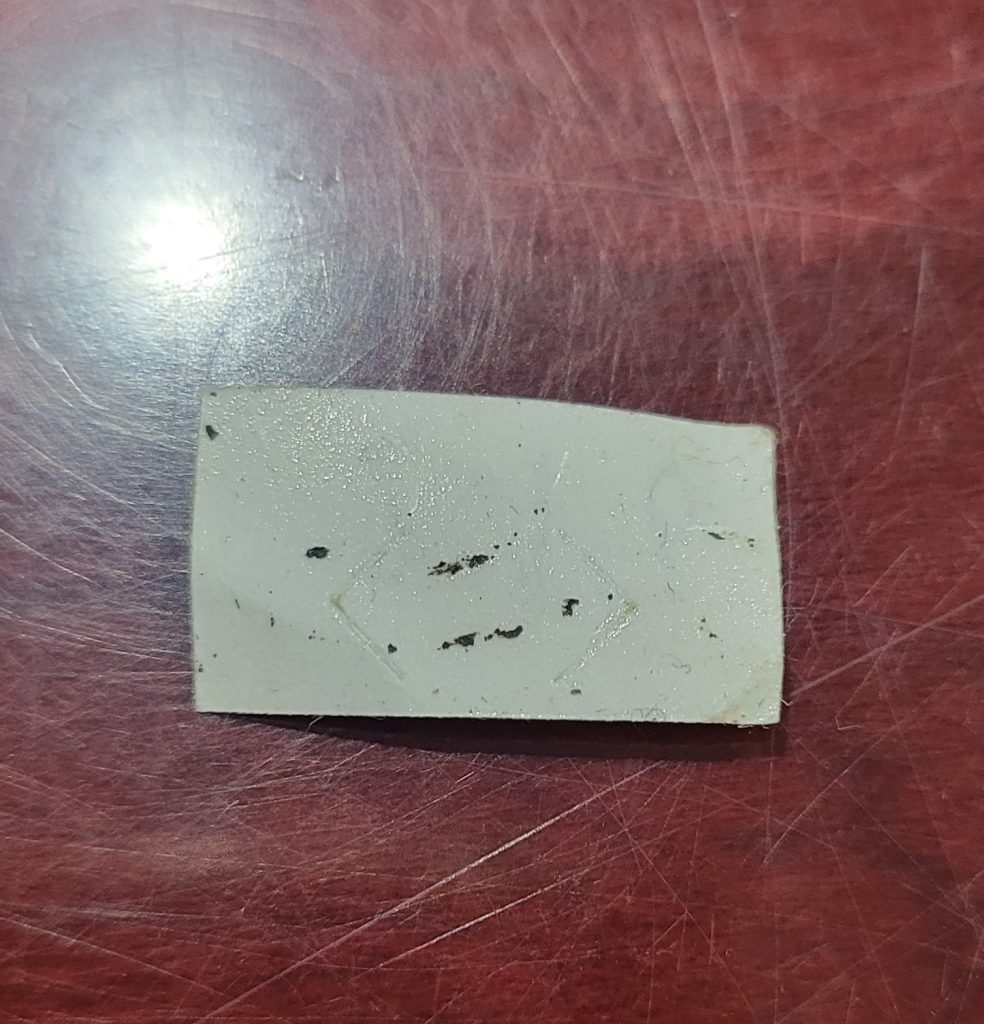

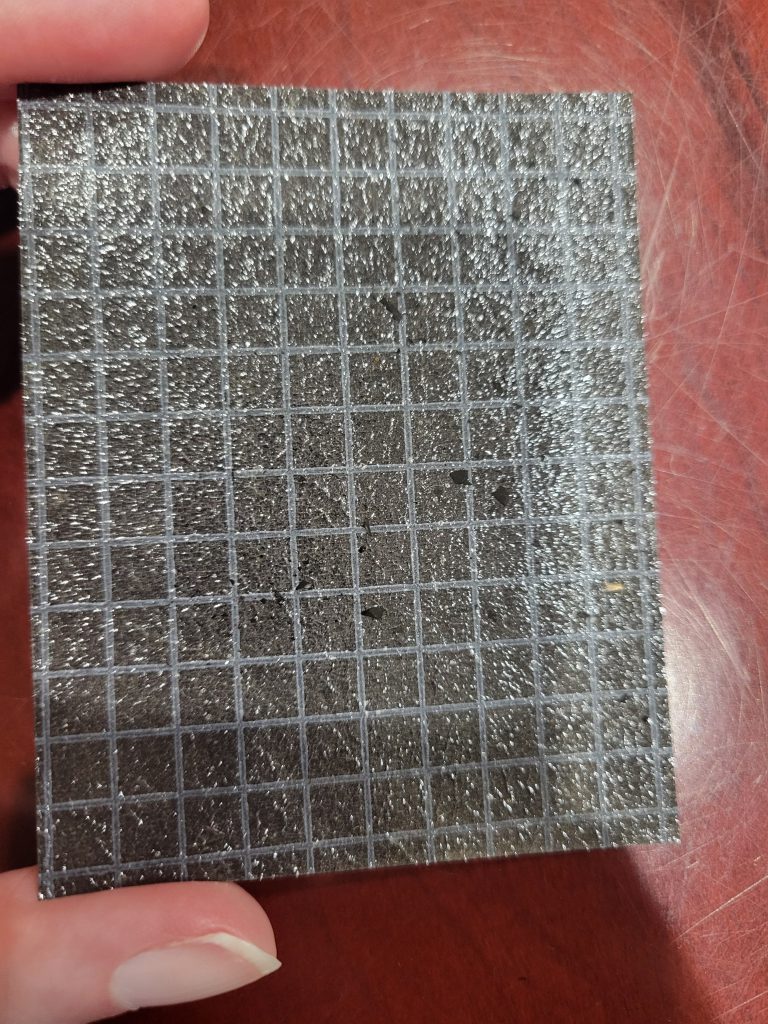

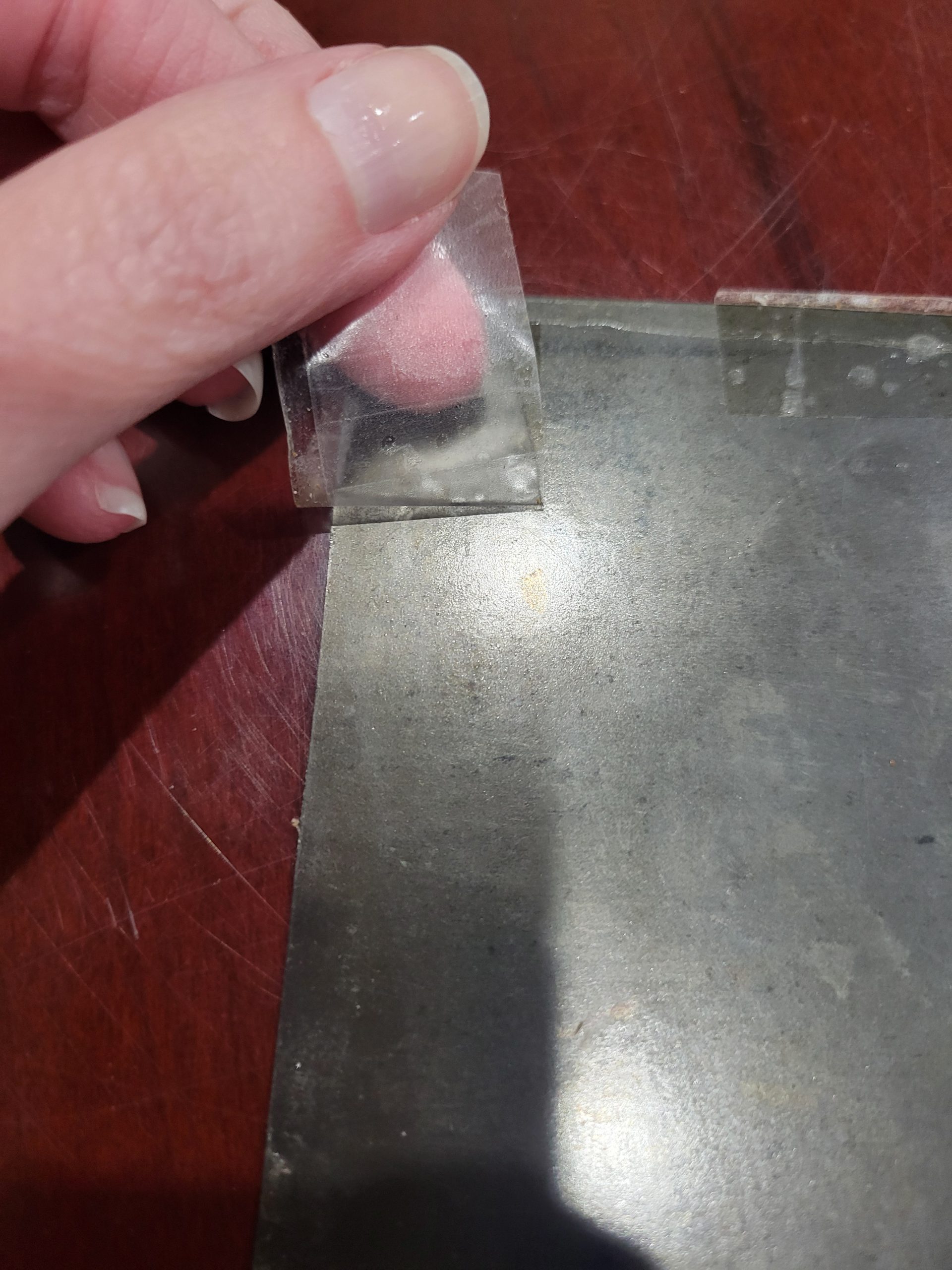

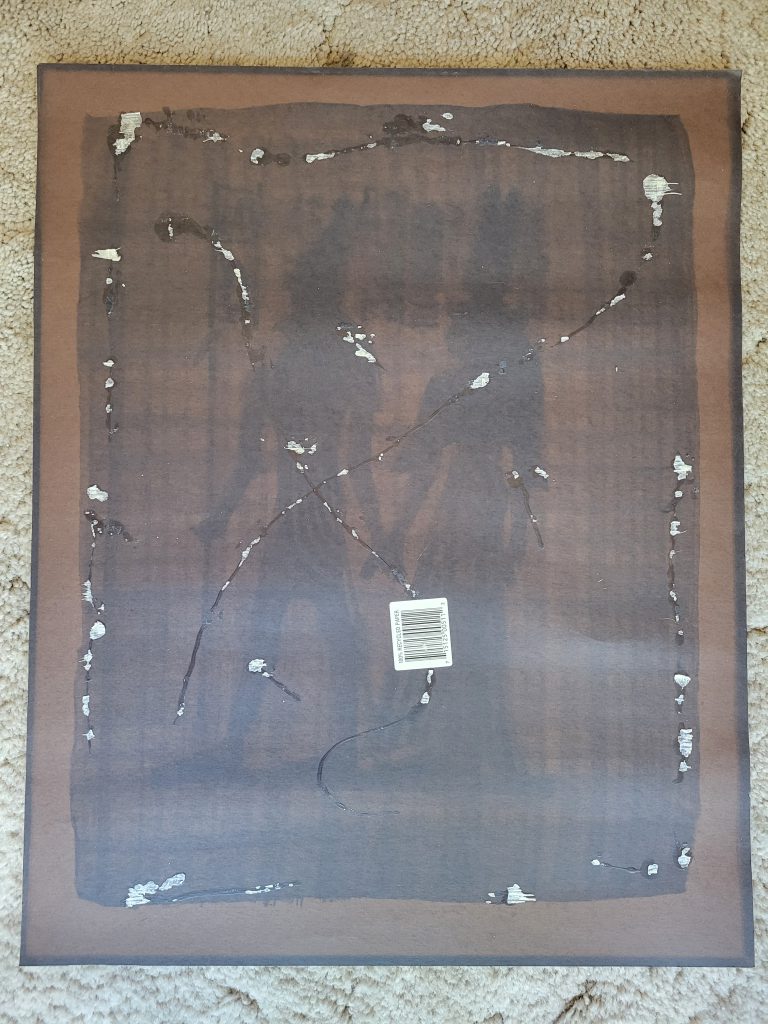

Once I dismantled the frame, I found this original papyrus illustration glued to a sheet of posterboard. And not small dabs of glue in each corner, GLUED. Swirls of glue all over that posterboard. I’d hoped that perhaps the glue was old enough that it would not have a good hold on the art anymore, and that the papyrus would just pop off from it. I was mistaken. In the immortal words of Elwood Blues, “this was glue. Strong stuff.”

I was able to slowly peel the papyrus off of the glue by working my hand between it and the posterboard very very slowly. It is important to note here that papyrus is stronger than old documents and paper in general. Because of the plant fibers it was tougher, but if you look at the photos, it still lost some pieces in the process. In addition, there are remnants of glue stuck to the back of the art that has essentially permanently bonded to it.

It is possible that this was some sort of water-soluble glue (ex. Elmer’s), but introducing water to try to remove it is extremely risky for any paper medium. As I’ve mentioned in previous archival posts, it is important that whatever you do with any historical document (or artwork) is reversible. Using a mountain of glue to stick it to non-archival posterboard is not reversible.

With Civil War-era documents you may even run across the infamous cheese glue (yes, that is a thing). And silly though it may sound, it is indeed strong stuff. When documents are glued together historically, I would refrain from attempting to separate them. However, this can be done in some cases by employing steam to attempt to release the glue. This is also very risky and damaging as it is introducing water vapor to a document which can wrinkle and warp it. However, if the document is unreadable or at risk by continuing to be glued to something, then it is generally worth the risk to mitigate that.

I am happy to report that this story has a happy ending as the hand painted souvenir trinket papyrus painting of the god Horus and Queen Nefertari was saved and is now hung up in a floating frame.

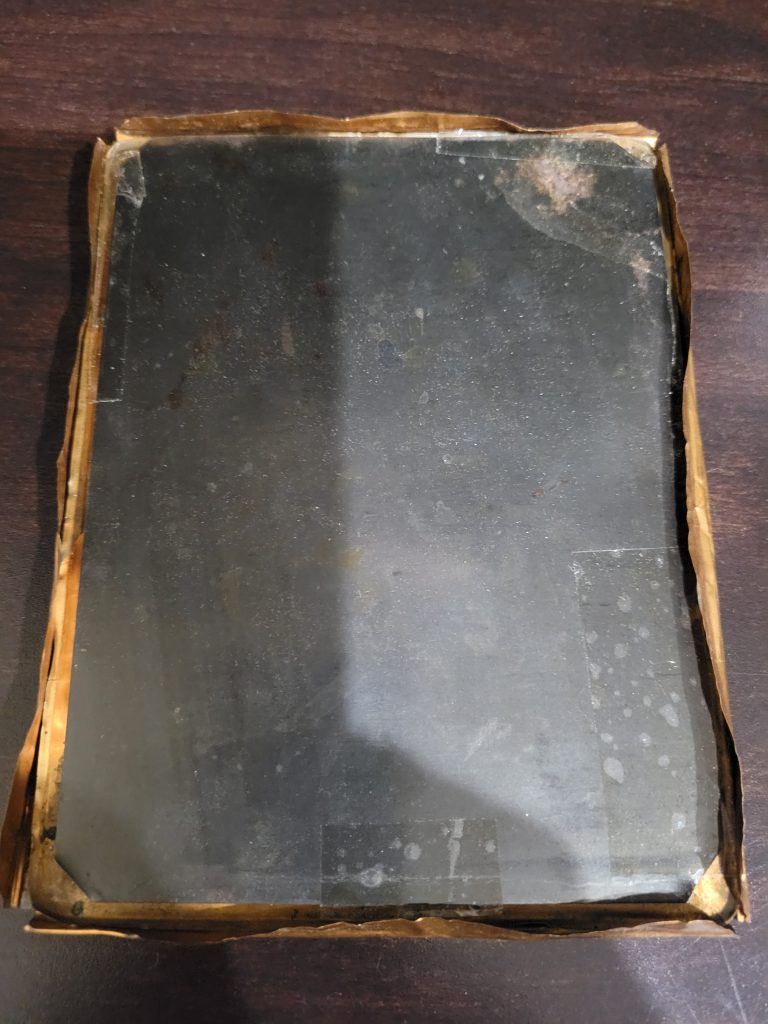

I would be remiss if I didn’t also mention that in the course of reframing about half a dozen of these pictures, I found a few where the artwork was mounted to posterboard using some kind of putty. This putty had the consistency of chewing gum and as you can imagine did not peel off well from a textured surface and also left stains behind. For future reference, please refrain from gluing or using chewing gum to mount any documents to posterboard. And please don’t use posterboard either as it’s non-archival and you can see how it faded in the pictures and even left a “ghost image” of the original artwork behind.

While this information may not apply to how you keep your Civil War documents, it is something to watch out for when framing beloved family photos or mementos—things that we often don’t consider historic. Because of that, we may not take the same considerations as we would with that hand-signed letter from Abraham Lincoln that is sitting in our collection. (Please don’t glue your Abraham Lincoln letters!) However, as time goes on and these family photos and souvenirs become older and intrinsic to family history, it is important that they are taken care of just as well.