Research Arsenal Spotlight 15: David Walker Beatty of the 63rd Pennsylvania Infantry

This week we’re going to focus on a collection of 48 letters written by Private David Walker Beatty of Company K, 63rd Pennsylvania Infantry. David Walker Beatty was born 1844 to parents Samuel Brown Beatty and Susan M. (Walker) Beatty. He had at least seven siblings.

David Walker Beatty mustered into the 63rd Pennsylvania Infantry on August 1, 1861. In October, 1861, his father, Samuel, enlisted in Company E of the 57th Pennsylvania Infantry. While beyond the scope of this spotlight, the Research Arsenal also contains an archive of over 40 letters written by Samuel Brown Beatty to his wife, Susan. In Samuel’s letters, David Walker Beatty was frequently referred to as “Walker.”

The 63rd Pennsylvania Infantry at Washington

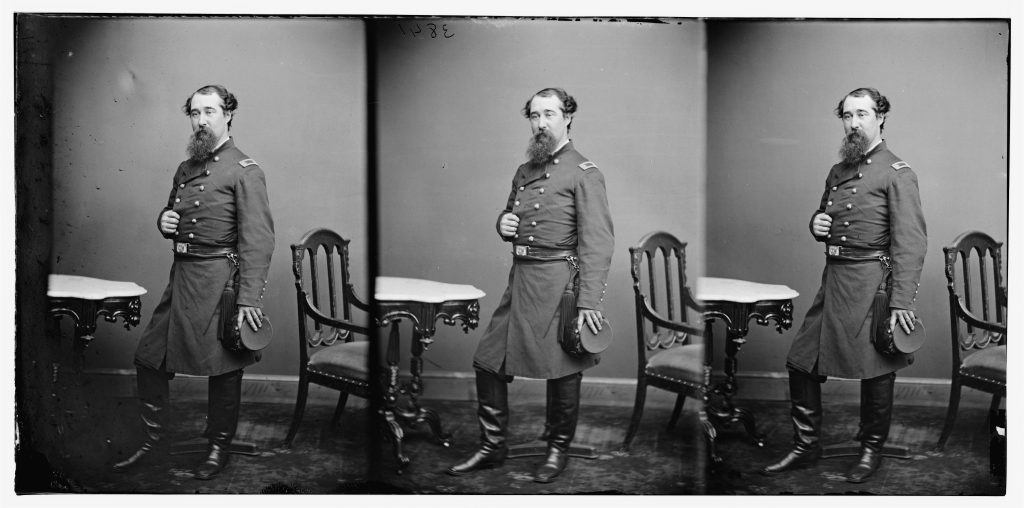

David Walker Beatty’s letters begin in September, 1861 while still in Pennsylvania. By October, 1861, the regiment was full and had been sent down to Washington. The 63rd Pennsylvania Infantry was under the command of Colonel Alexander Hays and the captain of David Walker Beatty’s company was Charles W. Chapman.

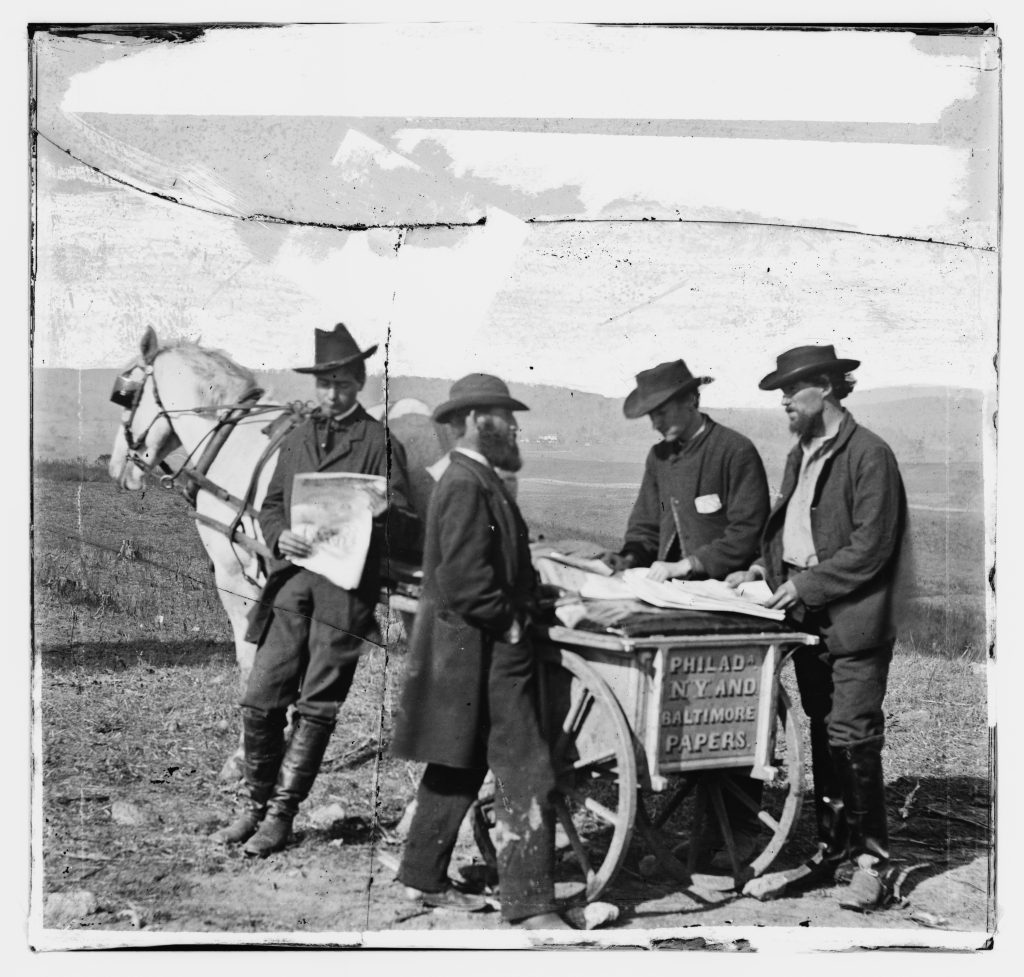

In a humorous letter to his mother written on October 12, 1861, David Walker Beatty addressed the newspaper’s propensity for exaggeration:

“I see it stated in the Pittsburgh papers that Col. Hays’ Regiment has all been killed and taken prisoners. We knew nothing of it until yesterday [when] we happened to see the Pittsburgh papers with an account of it. The paper stated that on the 5th we went down to the river to take a wash and the Rebels came on us and killed and took us all prisoners—what they did not kill, they took prisoners. That is a great story and no doubt many will believe it but it is too big a story to be true. On last Saturday the Colonel marched us all down to the river to take a wash but we seen no rebels. If we did, they were disguised for we did not know anything of the great defeat until we heard of it in the paper. You need not be scared about any such reports as that because we will not be killed without making some effort to save your lives. If the rebels get that close to us, we will know something about it and if they come in force, you may expect to hear of a battle.”

A couple weeks later David Walker Beatty learned his father had enlisted in the army and was quite upset and worried about it. He wrote about his fears to his mother in a letter dated October 27, 1861:

“I received a letter yesterday from Father dated Camp Curtin, October 24th, and was much surprised to hear of his being in the army and I felt very sorry for you. I do not see how you are to get along with such a large family to support. You never can get along without there is some better fix than when I was at home.

Mother, why did you let him go? You ought to have used all means in your power to have kept him at home. He had no business to go when there is so many that have no family to support and could leave home far better than he could. I think he will rue it yet. He said in his letter he has no cause for complaint yet but after he has been in the service about two months, he will find out a thing or two that he does not yet know. But he may stand it better than I think he will. Still, a man like him has no business in such a place as this.”

David Walker Beatty and the Battle of Seven Pines

The Battle of Seven Pines, also called the Battle of Fair Oaks, took place between May 31 and June 1, 1862. During the battle, both David Walker Beatty and his father Samuel Brown Beatty were part of the First Brigade of General Philip Kearny’s Third Division of the Third Corps.

David Walker Beatty gave a brief account of the battle to his mother in a letter dated June 2, 1862:

“We have had a big fight [Battle of Fair Oaks] and I suppose you will be a little uneasy about me but the most of us are safe. The battle came off on the 31st of May and the 1st of June. We gained nothing the first day but the second day we drove them back.

Our regiment was not in the fight the second day. Our regiment lost one hundred and forty men in killed, wounded, and missing. There was none killed in our company that we know of. There was three wounded and there is five missing yet. We suppose they are taken prisoners.”

A couple weeks later, David Walker Beatty wrote about the present duty his regiment was doing as pickets, and his belief another battle was near:

“We are now acting as a reserve for the pickets. We have been out since yesterday morning and will be here till tomorrow morning. It is pretty hard business as we do not get sleeping very much on account of the firing among the pickets. They are firing nearly all the time. We thought last night that we was going to have another battle as there was an attack made on our pickets and it continued nearly all night but our boys held their ground and captured about two hundred prisoners.

We were in the rifle pits all night and what little sleep we did get we had to sleep with our guns beside us. We had to get up about a dozen times on account of the heavy firing on the picket lines and the whole of our Division was moved up to the front in expectation of a fight. We are today stationed about a hundred yards in front of the rifle pits among some fallen timber and are waiting patiently for the Rebs to attack us as Sunday is their fighting day. We never make any attacks on Sunday.”

As it turned out, David Walker Beatty only had to wait a few more days. On June 25, 1862 the Battle of Oak Grove commenced.

Death of Samuel Brown Beatty

In the winter of 1862, Both the 63rd Pennsylvania Infantry and the 57th Pennsylvania Infantry fought in the Battle of Fredericksburg. At the time, David Walker Beatty was already in the hospital suffering from chronic diarrhea and did not participate in the battle.

In a letter from December 23, 1862, David Walker Beatty informed his mother of the sad results of the battle:

“I came here just the day before the fight commenced at this place and was therefore not in the fight. Our regiment was engaged but did not suffer very much. The 57th [Pennsylvania] suffered a great deal. Father was wounded in the leg but I guess not very severely. I did not see him after he was wounded. He was sent away to Washington to the hospital. The doctor of the 57th tell me that his leg will soon be well.”

Despite the optimistic prognosis, Samuel Brown Beatty had trouble recovering from his wound. Additionally, David Walker Beatty’s own condition continued to deteriorate. On January 25, 1863, he wrote wishing he could visit his father:

“I was very sorry to hear that Father is so poorly. I wish I was where I could get to see him. I should like to see him get home. I hope Uncle David will get him home if he can. Mother, I do not think you had better try to go down to see him unless you think there is no possibility of his getting well.”

After hearing of his father’s passing in early February, David Walker Beatty wrote a letter to his mother about the loss and imploring her not to apprentice out any of his siblings regardless of circumstances:

“Again I seat myself to write a few lines to you in answer to a letter which I received from you yesterday evening giving me the sad news of Father’s death. I heard of it several days ago and I feel very sorry but I hope he is better off. I hope he has gone where pain and sorrow are no more. Mother, bear up under the great affliction as well as you can. Was he buried at Salem or at Coolspring? But Mother, what do you intend to do. Will you try and keep the family at home yet or not? But one thing I want to tell you—don’t you bind out any of the children, whatever you do. If you have to let any of them go, let them go free.”

Tragically, this was very likely the last letter David Walker Beatty ever wrote. He died three days after it was written, on February 7, 1863 and was buried at the Soldiers’ Home cemetery in Washington, D.C.

We’d like to extend a special thanks to William Griffing of Spared & Shared for transcribing and sharing these letters.

If you’d like to read more of David Walker Beatty’s letters, or any of the thousands of others in our collection, you can do so with a Research Arsenal membership.

You can check out some of our other spotlight collections like Alfred Homer Johnson of the 30th Georgia Infantry and a photo album of members of the 25th Ohio Infantry.