Research Arsenal Spotlight 24: Silas Leach 52nd Pennsylvania Infantry Regimental Band

Silas Leach was born in Pennsylvania in 1836 to Isaiah Leach and Eliza (Kelly) Leach. Isaiah Leach worked as a school teacher and music teacher but passed away when Silas was only a year old. Silas, his siblings, and his mother then moved to Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania where his mother continued to live until her death in 1878. Silas was partially raised by his older brother, George W. Leach, who many of these letters were likely addressed to.

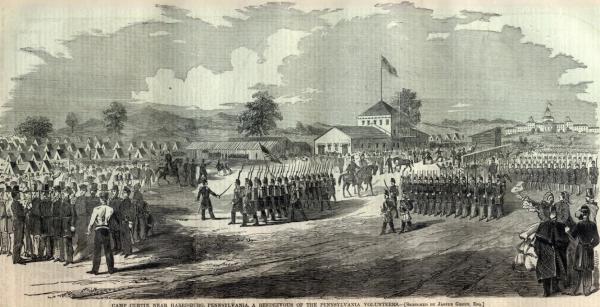

At the start of the war, Silas was a member of the Wyoming Coronet Band, which became part of the 52nd Pennsylvania Infantry. The 52nd Pennsylvania was organized at Harrisburg, Pennsylvania on November 5, 1861. Silas Leach’s first letter was written on October 29, 1861, from Camp Curtin, shortly before the regiment was formally mustered into service.

As a member of the regimental band, Silas Leach was not expected to do any fighting, but traveled with the regiment to provide music and do other duties.

Silas Leach at Camp Curtin

Camp Curtin, located in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, was one of the major hubs for mustering in new regiments and training soldiers throughout the Civil War. It is estimated that by the end of the war over 300,000 Union soldiers had passed through it.

In Silas Leach’s first letter home to his brother, written October 29, 1861, he spoke some of the difficulties of camp life which for the moment were confined to the chilly weather:

“The only serious inconvenience I have experienced since I have been here has been from the cold nights. We have had some very cold nights. I take off nothing but my blouse and shoes when I go to bed and then throw my overcoat on top the bed clothes. Last night I slept very comfortably.”

Silas Leach also recounted an incident about a fire taking place near Camp Curtin and the soldiers rushing to put it out:

“I suppose we will get away from here in the course of a week. Quite a little incident occurred the other day in camp. A barn just north of the camp took fire and about three thousand soldiers made a break right through the guard, went over and put it out. Quite a number of our band were prominent in putting out the fire and I attribute one invitation to dinner tomorrow to that fact. John Rohn, Bob Campbell, and myself being out on a prospecting tour after chestnuts did not have a chance to distinguish ourselves on that occasion.”

Silas Leach was very close on his prediction of when the 52nd Pennsylvania Infantry would move out. They left for Washington, D.C. on November 8, 1861.

52nd Pennsylvania Infantry in Washington, D.C.

In the winter of 1861 the 52nd Pennsylvania Infantry served as part of the defenses of Washington, D.C. On December 16, 1861, Silas Leach wrote to his brother about a rather humorous review of the troops in front of General McClellan:

“About half a mile from here is a large parade ground where most of the reviews on this side of the river take place. A few days ago I witnessed a review of Gen’l Keyes’ Division. It consisted of four brigades and was reviewed by Gen’l McClellan and staff. It was a very favorable day for the purpose and quite a large number of the beauty and fashion of Washington was there to witness the scene. I stood quite near McClellan and had a good chance to see what he looked like. He is quite robust and appears as if he gets enough to eat. Wears a mustache and quite firm expression of countenance generally. Gov. Morgan of New York was there [and] also Mrs. McClellan. Mrs. McClellan is quite young and quite good looking. She attracted great attention from its being her first appearance in public since her arrival from the West.

The only laughable incident that occurred was when the regiments were passing in review before the general, a drum major of one of the regiments was dressed up very finely and appeared as if he had a due sense of his own importance. When he got in front of McClellan, he gave his staff a pitch into the air intending to catch it when it came down. But unfortunately it fell in the mud and caused great laughter. And even McClellan relaxed his countenance enough to smile. The whole affair passed off in very good style.”

After receiving his pay, Silas Leach and a fellow member of the 52nd Pennsylvania Infantry Regimental Band, Charles Sutton, snuck off to Washington to do some sightseeing.

“While in the city, [Charley] Sutton and I went to the Capitol expecting to see Congress in session. But as usual they had adjourned until Monday. We went into the President and Vice President’s rooms. They were splendid rooms. I recognized the Vice President Mr. Hamlin having seen him in 1856. Charley and I had no pass and had to do some pretty tall dodging to keep out of the way of the patrol. We finally returned to camp. Very glad to get back. We have become so accustomed to walking on the ground that walking on pavements tires us out very quick.”

The End of Regimental Bands

By early 1862 it was clear that major reforms of the regimental bands were going to take place. While they had been initially seen as a powerful recruitment tool and morale booster, the sheer number of bands and band members proved costly to the war effort.

In a letter written on February 15, 1862, Silas Leach provided the first clue that regimental bands like those of the 52nd Pennsylvania Infantry might not be around for much longer, and that the uncertainty was causing a great deal of confusion among the men:

“The idea of putting us in the ranks is perfectly ridiculous. I have no doubt that some of them would like to have the power to do it. But they can’t come it. I have no doubt that we could get our discharge at almost any time by applying to the Secretary of War. But the boys would rather await the action of Congress.

You would laugh if you was here to hear the conversation that takes place. Sometimes the boys are very much down in the mouth. Talk about going home. At other times they feel very patriotic and wouldn’t go hence under any circumstance.”

On March 18, 1862, Silas wrote again to his brother after his regiment had spent some time in the field near Manassas, Virginia:

“I suppose you read of the advance made on Manassas and of finding the enemy ‘no whar.’ Most of the men that went from this side returned. They made a pretty hard appearance, having camped out in the rain and mud without any covering. They all expect to embark in the present expedition. I suppose we must now expect to soldier in real earnest. Thus far we have had very fine times.”

The final letter in our Research Arsenal collection was written on June 24, 1862. This was about one month before the issuance of General Orders No. 91 from the War Department, which ended the practice of regimental bands except for the regular drummers, fifers and buglers for each company. In this letter, Silas Leach advises against having a friend enlist:

“I see by the Record that the Ross Rifles were anxious to go into the tented field. Also noticed Oliver’s name amongst the list. Just tell Oliver if he has any regard for my advices, he will stay at home. I don’t say this because I am particularly sick of the business myself, but because I know he would be situated entirely differently from myself. We are exempt, in fact, from about all duties of a soldier, doing absolutely nothing. And I know Oliver well enough to know that after being a month in the service, he will feel like shooting himself to get out of it. It is far different here to what it was in Washington. There we could keep ourselves tolerably clean. But here it is almost impossible for a private to do so. If Oliver was here a day, I could show him enough to banish and scatter all his patriotism to the four winds.

You say there was a circus in town. They boys here all say that “This is the biggest traveling circus they ever saw.” In regard to the disposition of the band, nothing will be known or done until after Richmond is taken and the Lord only knows how long that will be.”

Silas Leach was discharged with the rest of the band on August 16, 1862. He died in 1902.

To learn more about regimental bands in the Civil War, read this article by the Library of Congress.

You can read more of Silas Leach’s letters, as well as view thousands of other Civil War letters, photos, and documents with a Research Arsenal membership.

We’d like to extend a special thanks to William Griffing of Spared & Shared for his work in transcribing and sharing these letters.

Check out some of our other Research Arsenal Spotlights like Tip Wilson of the 5th Tennessee Infantry and William Lewis Savage of the 10th Connecticut Infantry.