4 Benefits of a Digitized Collection

Last week, we went over some tips for scanning your collection. So, you’ve gotten a scanner and digitized your Civil War era photographs, letters, and documents. Now what? There are multiple ways to make use of your digital collection, but how far you decide to take is entirely up to you. Here are 4 benefits of a digitized collection.

1. Insurance

This is something I would highly recommend for every collector, and I’ve already harped on it in past blog posts, but please consider insuring your collection with a special policy. Many, if not most, home insurance policies will require “collectibles” to be itemized and covered separately. Having your collection digitized makes it much easier to have it appraised and submitted to your insurance company. The scans also provide a record of what you specifically have in your collection should any claims arise—but hopefully they never do!

2. Originals Safely Stored

Having your collection digitized means that you can safely store fragile elements of your collection. I understand that this is not practical for many collectors as they like to see their collection on display, but for some pieces, that may not be advisable. For instance, I have a beautiful official U.S. Senate portrait with its original frame from about 1885 or so. I removed the image from the frame, scanned it, and have it stored safely in my archive. I ordered a copy of the photograph and placed that inside the frame with a new archival quality mat, as the original was acidic and crumbling. That framed photograph now hangs on my wall at home, but the original is safely tucked away with no fear of fading or other damage. And I get the pleasure of having the original frame on display without worrying about it damaging the period photograph.

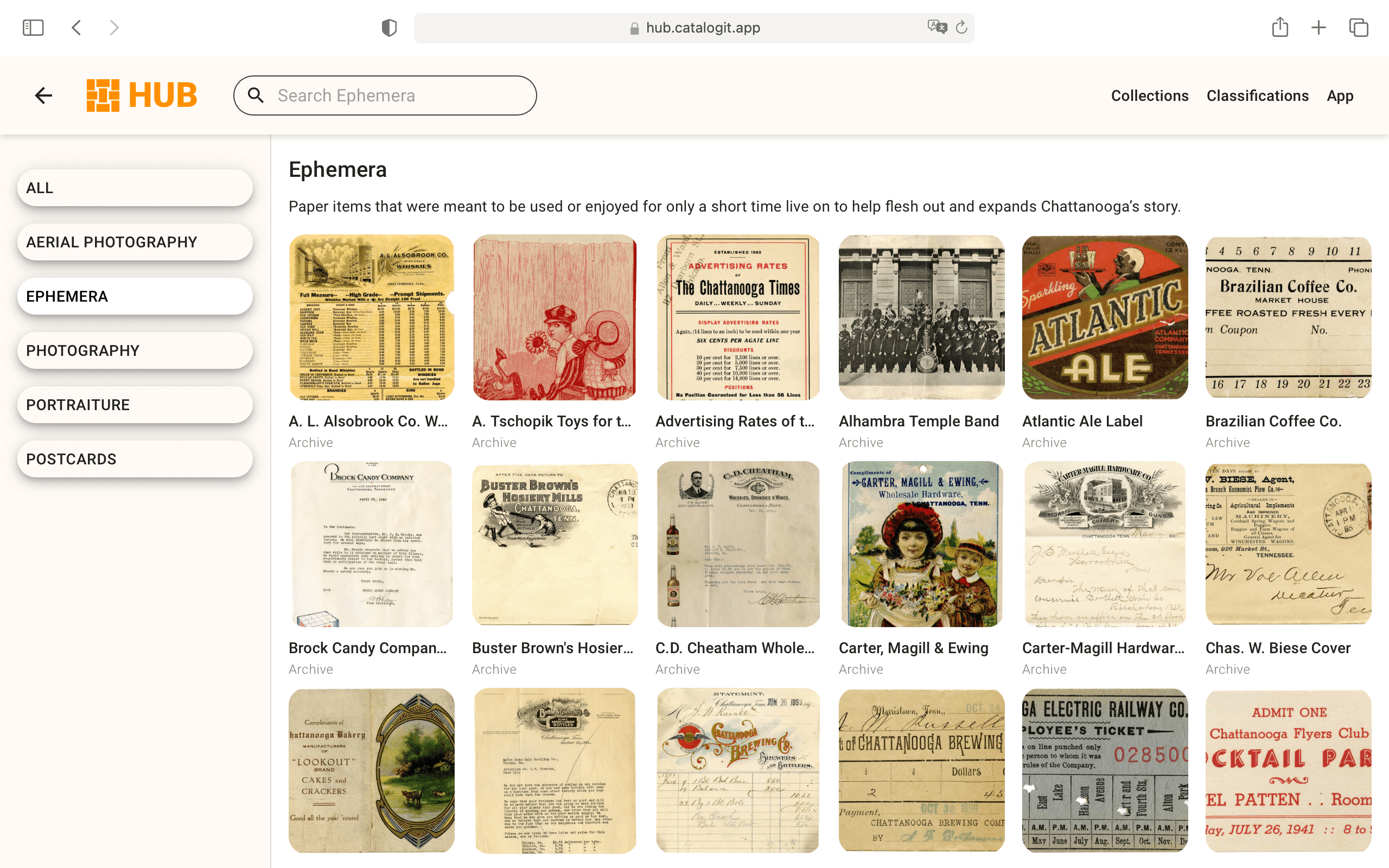

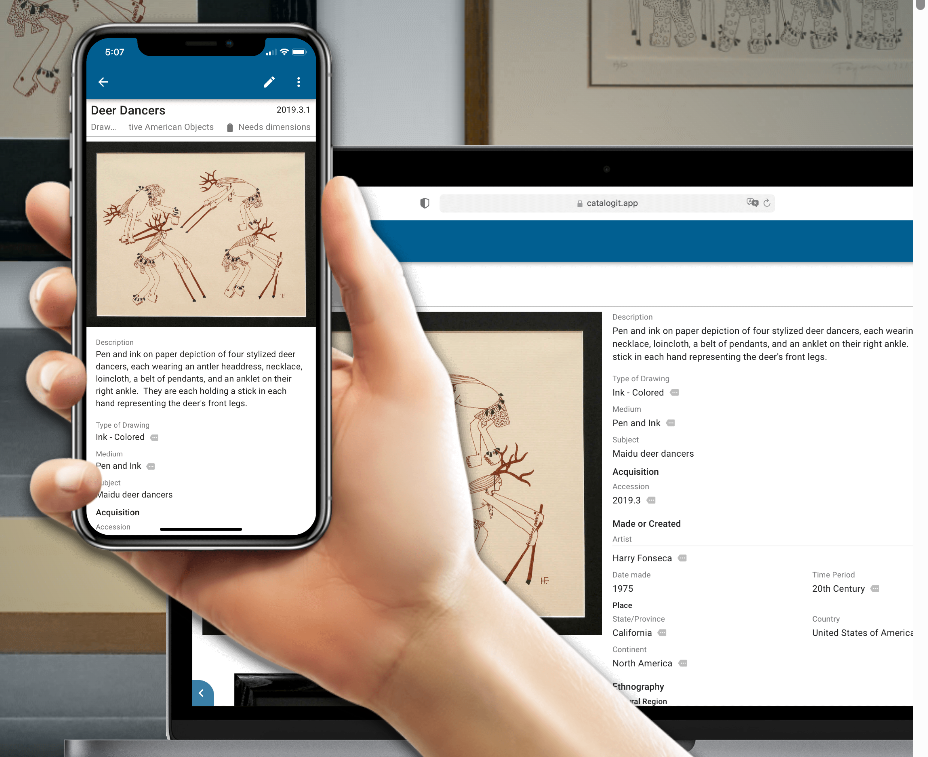

3. Virtual Exhibits

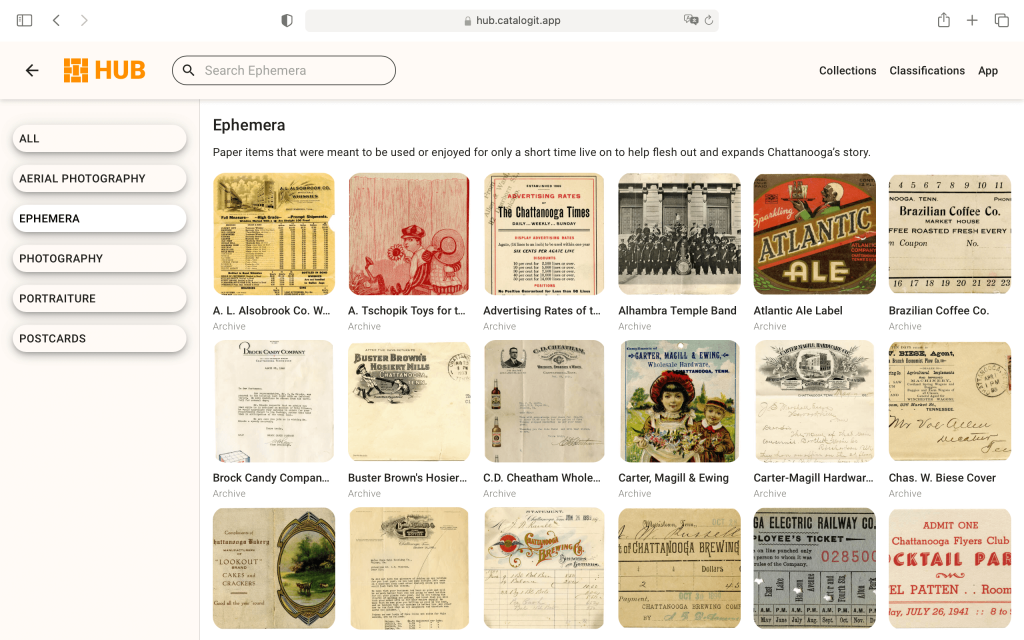

This is something that can be a bit of work, but the payoff can be immense. Depending upon your collection and the size of it, curating a virtual exhibit of it can be a fantastic way to share the knowledge you’ve accumulated while gathering your collection. It can also help connect you with other collectors and researchers knowledgeable in your area of interest. To a certain extent, any time you share a post on Facebook or Instagram about an item in your collection, you are creating a virtual exhibit of a single item. However, there is software available to make collections more accessible. Whether you are using a simple WordPress site or using collection management software like CatalogIt or PastPerfect, sharing your collection with others can lead to new information, and possibly new acquisitions.

4. Sharing with Museums

This can be a bit of a sticking point with some collectors as they tend to gather things into their collections, shout “MINE!”, and then proceed to make sure that nothing in their collection ever sees the light of day. As a researcher, I have encountered this, and as a researcher, I tend to make available things that I have because I know what it’s like when you’re writing a book on something and you can’t get that last bit of information because someone has it squirreled away somewhere.

To give you an example, I have been involved with the Fort Caspar Museum in Casper, Wyoming for over a decade and the museum has been around since the 1930s. The city of Casper is named after the fort, which was named after young Lt. Caspar W. Collins of the 11th Ohio Volunteer Cavalry killed in battle here on July 26, 1865. We do not have a single adult photograph of Caspar Collins. We have one photograph of him as a toddler, and that’s it. Now, he spent much of his service with his father, Col. William O. Collins, and I think it is safe to assume that he likely had his photograph taken at some point in his service, and likely one with his father. I also think it is reasonable to assume that that photograph is sitting somewhere in someone’s collection or collecting dust in an attic. That collector may have no idea we’re looking for that photograph, and likewise, he has no idea that he’s sitting on some unidentified 11th Ohio Volunteer Cavalry trooper photograph that we could likely identify. Unless that information makes it online somewhere, we are unlikely to ever cross paths so we will continue to hope and wait that a Caspar Collins photo pops up on the internet, and that collector will continue to own that photo without realizing who it is.

I’ve also tried to track down photographs of Civil War soldiers killed while in service out here who are being honored with headstones. I’ve added 22 headstones over the last few years and only have 2 photographs. I’m sure that there are more out there—especially of the officers—but they are likely not identified, or housed in a collection with someone who hasn’t seen my Facebook posts looking for them, or worse, isn’t even aware that they have those photographs. Some collections become so large and unmanageable that it is next to impossible to keep track of everything. As collectors age and pass away, that knowledge goes with them and the collections are liquidated reducing identified soldiers to now unknowns.

The point of this larger entry is to encourage collectors to share what they have. If not literally copies of scans, to at least make themselves known to local institutions. So when a museum in Wyoming reaches out to a museum in Ohio looking for a Caspar Collins photograph, the curator in Ohio could pass our query on to someone who might possibly be able to help. Otherwise, it’s like playing a decades-long game of “Go Fish” calling and trying to find these sorts of things. Not only would you be helping these institutions, but they may also have information and items in their collections that could help you learn more about what you have and provide more context for you.

From preservation, to ease of access, to virtual exhibits, having a digital copy of your collection is priceless. I hope it’s not something that ever has to be used in the case of an insurance claim, but it will be extremely important to have in that type of event. If there is interest in how to set up a virtual exhibit, I can share some information on that topic in future posts. Just leave a comment or message us on Facebook!