Illuminating the Past Without Destroying It: Safe Lighting for Exhibiting Your Collection

When we walk into a museum or gallery, the first thing we often notice is the light. It sets the mood, guides our eyes, and brings the details of fragile objects into focus. Yet, the very thing that allows us to see history can also destroy it. Light—whether from the sun, a gallery spotlight, or even dim ambient sources—causes irreversible harm to artifacts. Fading, yellowing, and weakening of fibers all accumulate quietly over time, leaving objects permanently altered. Museums face the difficult challenge of balancing accessibility with preservation: making objects visible to the public while also protecting them for the future. This is the same challenge that private collectors face while being the caretakers of historic artifacts.

And if this is a challenge in museums, it’s really going to be a challenge in personal homes. However, private collectors can follow museum best practices as best they can and that will help prolong the life of their collection.

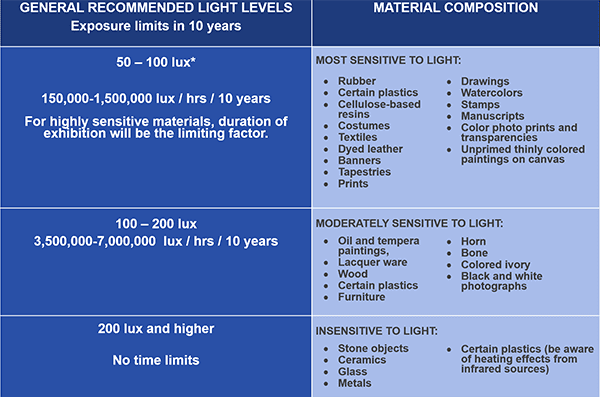

The Conservation Center for Art & Historic Artifacts (CCAHA) emphasizes that light damage is cumulative and cannot be undone. Once colors fade or paper embrittles, there is no restoration to its original state. What’s more, light damage doesn’t occur evenly—certain materials are vastly more sensitive than others. Photographs, textiles, and works on paper are particularly vulnerable, while ceramics, metals, and glass are more forgiving. But even the strongest object will eventually show the effects of long-term exposure if left unchecked.

The science of safe lighting revolves around two major considerations: how bright the light is, and how long an object is exposed to it. Brightness is measured in lux (lumens per square meter), and cumulative exposure is calculated as lux multiplied by time, known as “lux-hours.” To put this in perspective, imagine a manuscript displayed under 100,000 lux of daylight for just one hour—that’s the same exposure as keeping it under dim 50 lux gallery lighting for two thousand hours. The math makes clear why even “safe” low light levels can become dangerous if the duration stretches too long.

Because of these risks, museums follow general guidelines for different categories of sensitivity. The most fragile objects—things like photographs, textiles, and paper documents—should not be illuminated above about 50 lux, and even then only for brief periods. Moderately sensitive artifacts, such as oil paintings, wood, or leather, can tolerate up to 150 lux, while sturdier items like metals or ceramics can withstand up to 300 lux. The difference might not seem dramatic to the naked eye, but for the objects themselves it can mean decades of preservation versus rapid decline.

It isn’t just visible light that causes harm. Ultraviolet (UV) radiation, which the human eye cannot see, is especially destructive. Museums work hard to minimize UV exposure by using specialized bulbs, applying UV-filtering films to windows, or installing protective acrylic glazing on display cases. Even then, filters degrade over time and need replacement every decade or so. Without these measures, daylight streaming innocently through a window could cause a vivid textile to fade in just a matter of months. UV light can also rapidly fade and yellow historic papers. It will fade the writing off handwritten documents and wash out photographs quickly.

Another equally important aspect of protection is time. Restricting how long an object remains on display is often the best safeguard. Institutions often rotate collections, allowing fragile objects only a few months of exhibition every few years, then resting them in dark storage for long stretches in between. In some cases, facsimiles or digital reproductions stand in for the originals, especially when public demand for viewing is high and conservation concerns outweigh continuous display. To further cut down on exposure, some museums use motion sensors or timed lighting systems so that cases illuminate only when visitors are nearby. While collectors often want their collections on permanent exhibit, rotating items is definitely something to consider. If that’s not possible, I would recommend displaying the collection in a room that is in darkness most of the time with no windows.

Monitoring is also critical. Conservators regularly measure light and UV levels with handheld meters or data loggers, keeping track of an object’s cumulative exposure. Test cards and spectrophotometers may be used to check fading rates, particularly for valuable or unusually fragile items. Over time, museums build careful records of each artifact’s exposure history, ensuring that no single piece receives more than its safe share of light across multiple exhibitions. This is important because if something is being damaged gradually, you are not likely to notice it until it is too late. These devices that can track that data will be able to tell you if something is at risk even if you can’t see it.

This constant balancing act between visibility and protection shapes the design of entire exhibitions. Galleries often remain in darkness outside of public hours, with blackout shades pulled tight over windows. Cases are designed with UV-filtered glazing, and even the interior lighting is carefully designed to ensure it falls within recommended ranges. Light boxes, where illumination passes through an object from behind, are typically avoided because of their intensified effect on sensitive materials. Everything about the display environment is engineered to minimize harm while still allowing visitors to engage meaningfully with the past.

At first glance, these rules might sound overly restrictive—fifty lux seems impossibly dim compared to the lighting in most public spaces. Yet our eyes adapt remarkably well to low levels of illumination, especially in darkened gallery environments. What feels like a hushed, intimate setting is, in fact, an intentional design choice. By lowering overall brightness, curators make the most fragile objects legible without overwhelming them. Visitors often leave with a heightened sense of atmosphere, not realizing that the ambiance is as much about conservation as it is about aesthetics.

The lesson in all this is that light, while essential, must be treated as a carefully controlled tool rather than a neutral presence. The objects entrusted to museums carry centuries of history, and their survival depends on choices made today about how brightly they are lit and how long they are exposed. By respecting safe thresholds, rotating displays, filtering UV, and monitoring conditions, curators ensure that artifacts endure.

For those of us who collect historic objects these same principles apply. Limit direct sunlight, use UV-filtering glass or films, choose lower-wattage bulbs, and think about how long objects are exposed. Remember that every hour of illumination adds up. The goal isn’t to lock history away in darkness, but rather to reveal it thoughtfully—balancing access with stewardship. This ensures that our collections will live on long beyond us.