The Battle of Antietam: First-Hand Accounts

The Battle of Antietam: First-Hand Accounts

On a foggy morning of September 17, 1862, the fields around Sharpsburg, Maryland, were transformed into the single bloodiest day in American military history. The Battle of Antietam (or the Battle of Sharpsburg, as Southerners called it) brought Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia into violent confrontation with Major General George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac. In the span of twelve hours, more than 22,000 men were killed, wounded, or missing—that’s over 1,800 men per hour. Beyond its staggering human cost, Antietam changed the direction of the war and, in many ways, the nation itself.

Lee’s Gamble

In September 1862, buoyed by victories at Second Manassas, General Robert E. Lee made the daring decision to carry the war into Union territory. His goals were ambitious: disrupt Northern morale, encourage Maryland to join the Confederacy, resupply his army, and perhaps secure diplomatic recognition from Britain or France. McClellan, moving cautiously as ever, learned of Lee’s plans when Union soldiers discovered a copy of Special Order 191. Even with this advantage, McClellan delayed, giving Lee time to concentrate his scattered forces at Sharpsburg, where they took defensive positions behind Antietam Creek.

The Battle Begins

At dawn on September 17, Union General Joseph Hooker led the opening assault against the Confederate left. The fighting in the Cornfield near the Dunker Church became a nightmare of smoke and musketry. Regiments surged forward and fell back, often leaving heaps of dead and wounded where they stood only minutes before.

In the center of the line, Union forces struck a sunken farm road, quickly christened “Bloody Lane.” The Confederates used the eroded roadbed as a makeshift trench, repelling wave after wave of attackers until their lines finally broke. Although Union troops captured the position, they failed to press their advantage.

Later in the afternoon, Union General Ambrose Burnside launched an attack on the Confederate right, attempting to cross a narrow stone bridge over Antietam Creek. For hours, his men faced withering fire from Confederate marksmen. At last, Burnside’s men surged across and began to push the Confederates back toward Sharpsburg. But just as victory seemed possible, A. P. Hill’s “Light Division,” marching twenty miles from Harpers Ferry, arrived on the field. Their timely counterattack drove Burnside back and saved Lee’s army from destruction.

Stalemate, Yet Turning Point

By nightfall, neither side had gained a decisive advantage. Lee’s army held its ground on September 18, then slipped back across the Potomac the following night. McClellan, wary of Lee’s strength, failed to pursue. Militarily, the battle was a draw.

But strategically, Antietam was a Union victory. Lee’s first invasion of the North had been stopped. More importantly, the outcome gave President Abraham Lincoln the confidence to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, redefining the war as a struggle not only to preserve the Union but also to end slavery in the rebelling states. Foreign powers, particularly Britain and France, were now far less likely to recognize the Confederacy.

The cost was enormous: Union casualties numbered about 12,400, including more than 2,100 killed. Confederate casualties were around 10,300, with some 1,600 killed. In one day, more than 22,000 Americans became casualties.

First-Hand Accounts from the Field

“Badly bruised, the Colonel was making his way northward when he realized he had lost his sword. Those by his side tried to persuade him not to return for the cherished possession, but his reply was ‘Yes I will, that sword was given to me by my men and I told them I would protect it with my life and never see it dishonored, and I am not going to let them damned rebels get it.’ “

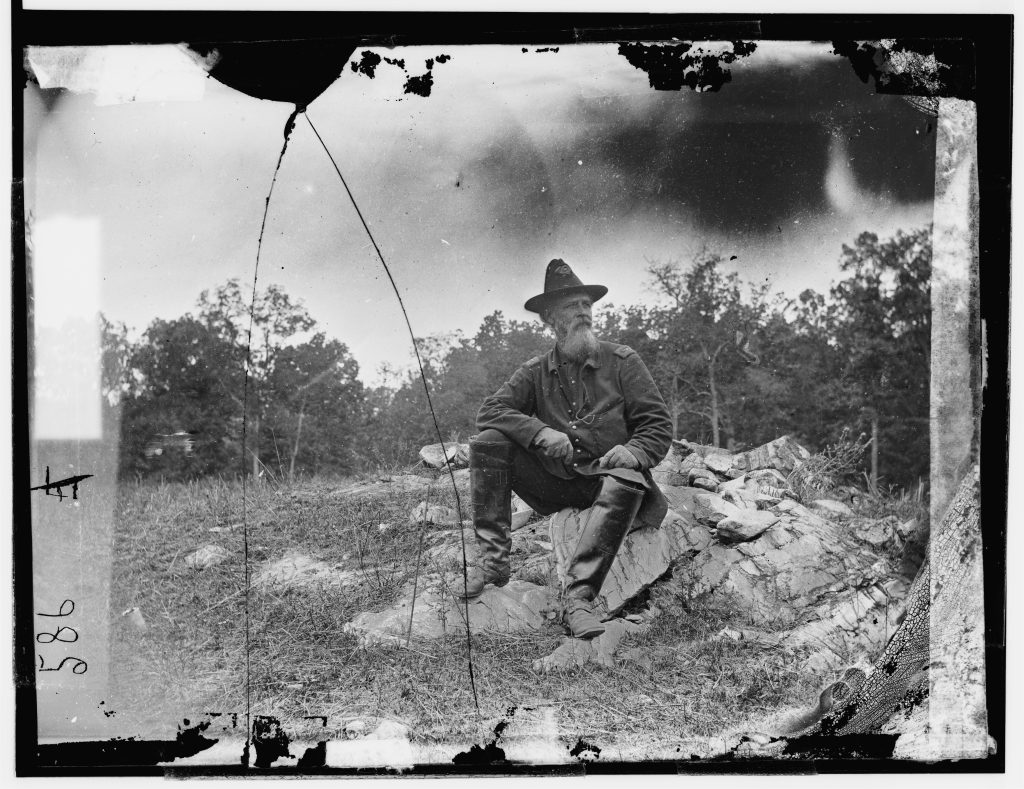

“Morehead rushed back to where his horse lay and recovered the sword. The enemy, by then only yards away, ordered Morehead to surrender. He refused and fled northward amid a volley of enemy rifle fire. None of the bullets hit its mark, and the Colonel made it safely to friendly lines in the vicinity of the Miller house.” Image: https://app.researcharsenal.com/imageSingleView/1085

There is no substitute to primary accounts of an historical event. These are just some of the many voices from the battlefield:

Major Rufus R. Dawes, 6th Wisconsin Infantry

In the Cornfield, Major Dawes of the famed Iron Brigade witnessed the chaos firsthand:

“A long, steady line of rebel gray, nothing shaken by the fugitives who fly before us, comes sweeping down through the woods around the church. They fire. It is like a scythe running through our line. ‘Now, save, who can.’ It is a race for life that each man runs for the cornfield.”

Dawes later recalled how men were “knocked out of the ranks by the dozens.” He also remembered the death of Captain Werner Von Bachelle of Company F, whose loyal Newfoundland dog refused to leave his master’s body, dying beside him. The two were buried together.

Surgeon William Child, 5th New Hampshire Volunteers

For medical staff, the aftermath was often worse than the battle itself. The emotional toll faced by surgeons in primitive field hospitals would have been traumatic to say the least. Surgeon William Child wrote home:

“The days after the battle were a thousand times worse than the day of battle. I dressed 64 wounded men that day—many with two and three wounds each.”

Private Alexander Hunter, 17th Virginia Infantry

On the Confederate side, Private Hunter captured the sounds of the battle in poetic imagery:

“It was no longer alone the boom of the batteries, but a rattle of musketry—at first like pattering drops upon a roof; then a roll, crash, roar, and rush, like a mighty ocean billow upon the shore.”

A Soldier’s Loss

Another unnamed soldier recorded the moment he marched past the body of his own father, killed in a nearby regiment.

“A wounded man, who knew them both, pointed to the father’s corpse, and then upwards, saying only, ‘It is all right with him.’ Onward went the son, by his father’s corpse, to do his duty in the line, which, with bayonets fixed, advanced upon the enemy. When the battle was over, he came back. and with other help. buried his father. From his person he took the only thing he had. a Bible, given to the father years before, when he was an apprentice.”

Remembering Antietam

Today, Antietam National Battlefield preserves these rolling fields and quiet roads, places once filled with the roar of cannon and cries of the wounded. To walk through the Cornfield, stand at Bloody Lane, or gaze across Burnside Bridge is to be confronted by the staggering human price of the conflict.

Antietam was not the final battle of the Civil War, nor was it the bloodiest overall. But in a single day, it forced the nation to reckon with the terrible costs of division—and pointed toward a broader vision of freedom. Through the words of those who endured it, we remember not just strategy and numbers, but the courage, grief, and sacrifice of the individuals who lived through September 17, 1862.

Antietam on the Research Arsenal

You can filter each library on the Research Arsenal by battle and applying that filter with the term “Antietam” brings up 38 letters and diaries related to the battle, as well as 45 photographs. In addition, you can search for specific regiments involved in the Ordnance Returns, Clothing Ledgers, Morning Reports, and Military Forms libraries for additional search results.

Sources

- Britannica. Battle of Antietam. https://www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-Antietam

- Smithsonian National Museum of American History. The Battle of Antietam: Turning Point. https://americanhistory.si.edu/explore/exhibitions/price-of-freedom/online/civil-war/turning-points/battle-antietam

- American Battlefield Trust. Battle of Antietam. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/civil-war/battles/antietam

- National Park Service. A Short Overview of the Battle of Antietam. https://www.nps.gov/articles/a-short-overview-of-the-battle-of-antietam.htm

- National Park Service. Letters and Diaries of Soldiers and Civilians. https://www.nps.gov/anti/learn/education/classrooms/antietam-letters-and-diaries-of-soldiers-and-civilians.htm

- Dawes, Rufus R. Service with the Sixth Wisconsin Volunteers. Quoted in Iron Brigader: https://ironbrigader.com/2012/09/18/rufus-dawes-6th-wisconsin-infantry-describes-fighting-cornfield-antietam/

- Wikipedia. Battle of Antietam. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Antietam