From Maine to the Gulf: The 2nd Maine Cavalry’s Civil War Journey

From Maine to the Gulf: The 2nd Maine Cavalry’s Civil War Journey

The 2nd Maine Cavalry Regiment is a fascinating example of a Civil War unit that traveled far from home and faced unusual challenges. Raised in the Pine Tree State late in the war, these cavalrymen found themselves fighting guerrillas in Louisiana swamps, charging Florida villages, and besieging Confederate forts in Alabama. Along the way, they endured a far deadlier enemy than Southern bullets: disease. In this post, we’ll explore the formation, deployments, battles, and ultimate fate of the 2nd Maine Cavalry. We’ll also highlight colorful anecdotes – from daring raids to single-handed heroics – and discuss the treasure trove of digitized regimental records (descriptive books, letters, order books, morning reports, etc.) that shed light on the men of the 2nd Maine and the impact of sickness on their ranks.

Formation of the 2nd Maine Cavalry

By late 1863, Maine had already contributed one cavalry regiment (the 1st Maine Cavalry) to the Union cause. A decision was made to raise a second regiment of mounted troops. Organizing at Augusta, Maine in the winter of 1863, the unit officially mustered into service on January 12, 1864. Governor Cony of Maine sought volunteers for a 3-year term, though sources note the regiment was mustered for about 23 months of service (likely anticipating the war’s end). The new regiment attracted over a thousand men from across Maine. They were led by Colonel Ephraim W. Woodman, appointed as the regiment’s commanding officer.

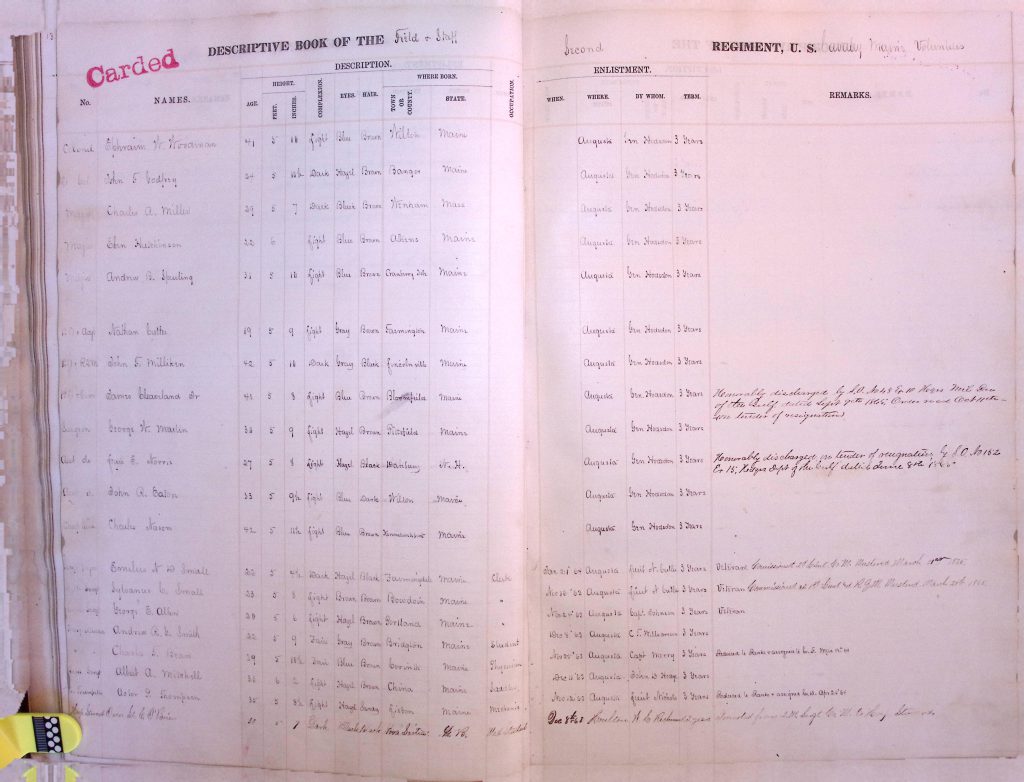

The Regimental Descriptive Book, now digitized in the Research Arsenal archives, lists every soldier who joined the 2nd Maine Cavalry. In it one can find each man’s name, his company (A through M), and basic details like age, physical description, occupation, and enlistment date. This creates a full roster of the regiment’s members – from seasoned officers like Col. Woodman to fresh-faced privates. Such details help us imagine the composition of the unit: hardy lumbermen, farmers, and fishermen from Maine, suddenly preparing to serve on horseback in a far-off theater of war.

After organizing and training through the winter, the 2nd Maine Cavalry departed the frigid Northeast for a very different climate. In April 1864, the regiment left Maine for the Department of the Gulf, part of a transfer of Union forces to reinforce campaigns in the Deep South. Many of these Maine men had never left New England; now they faced a long journey by rail and steamship toward the Gulf of Mexico.

Duty in Louisiana: Defenses of New Orleans and the Red River Campaign

Upon arrival in New Orleans in spring 1864, the 2nd Maine Cavalry was attached to the Union forces guarding southern Louisiana. They performed picket and scouting duty in the defenses of New Orleans through May 1864. This relatively quiet period ended when a portion of the regiment was drawn into the ongoing Red River Campaign – Union General Nathaniel Banks’s ill-fated attempt to invade Texas via the Red River in Louisiana.

In mid-April 1864, Companies A, D, and G of the 2nd Maine were detached from the main regiment and sent to Alexandria, Louisiana to bolster Banks’s army. There they skirmished with Confederate forces and guerrillas in the swampy bayous. For several tumultuous weeks, these Maine cavalrymen covered the federal retreat from the Red River, fighting in sharp actions at Marksville (Avoyelles Prairie) on May 15, 1864, at Mansura on May 16, and at Yellow Bayou on May 18. At Yellow Bayou – the last battle of the Red River Campaign – Union troops fought a rearguard action to fend off pursuing Confederates. The Maine troopers helped hold the line. By late May 1864, Banks’s battered force escaped, and the detached companies rejoined the rest of the 2nd Maine Cavalry at Thibodeaux, Louisiana on June 1.

Meanwhile, Colonel Woodman and the majority of the regiment remained stationed in the District of La Fourche (the area around Thibodeaux and Brashear City) during April–July 1864. They conducted frequent scouting expeditions and anti-guerrilla operations. One young officer, Major Andrew B. Spurling, made a name for himself during this time. Spurling had transferred from the veteran 1st Maine Cavalry and took command of several companies in the field. Near Brashear City (modern Morgan City), Spurling led his men in running battles against Confederate guerrillas harassing Union supply lines.

By July 1864, the 2nd Maine Cavalry had acclimated to soldiering in Louisiana’s heat. They had seen a bit of action (especially those detached companies) and were now seasoned enough for more active operations. That summer, a new campaign beckoned – this time eastward to Florida, a region with few Union troops but plenty of Confederate activity.

On to Florida: Pensacola and the Raid on Marianna

In late July 1864, the regiment received orders to move to the Florida Panhandle. They embarked from Algiers (near New Orleans) and arrived at Pensacola, Florida by August 11, 1864. Pensacola’s Union-held Fort Barrancas became the 2nd Maine’s new base of operations. The strategic aim was to project Union power into western Florida, to disrupt Confederate supply lines and stop refugees or troops moving east from Alabama.

For the next several months, the 2nd Maine Cavalry was the backbone of Union cavalry raids across the Gulf coast of Florida and Alabama. A notable early encounter came on August 25, 1864, when a detachment skirmished at Milton, Florida, a small town north of Pensacola. As summer turned to fall, a much larger expedition was planned that would become the regiment’s most famous action: the Marianna raid.

The Battle of Marianna – “Florida’s Alamo”

In September 1864, Brigadier General Alexander Asboth, the Union district commander at Pensacola, organized a raid deep into northwestern Florida. His target was Marianna, Florida, a town believed to be a recruitment center and refuge for Confederates (and reportedly housing Union prisoners). Asboth assembled about 700 troopers, including three battalions of the 2nd Maine Cavalry under Lt. Col. Andrew Spurling and one battalion of the 1st Florida U.S. Cavalry (Unionists from Florida), plus a few companies of U.S. Colored Infantry. On September 18, the column rode out from Fort Barrancas, trekking over 200 miles through woods and swamps.

After more than a week of hard riding and small skirmishes, Asboth’s force reached Marianna at noon on September 27, 1864. The town’s defense fell to a mix of Confederate cavalry and local home guard militia hastily gathered by Col. Alexander Montgomery. As the Union troopers approached, they encountered an ambush. Without fully reconnoitering the situation, Gen. Asboth ordered Major Nathan Cutler to lead his 2nd Maine battalion in a headlong charge down Marianna’s main street. The Maine cavalrymen galloped in – and were met by shotgun and musket fire from militiamen concealed in houses and behind fences. Major Cutler’s men were staggered by the point-blank volley and had to pull back. Immediately, Major Eben Hutchinson led a second battalion into the fray, clearing some barricading wagons and pushing further in, only to be blasted by another close-range volley. Both Maj. Cutler and Maj. Hutchinson were severely wounded in these charges. Even Gen. Asboth was shot from his horse (he took a bullet to the cheek and arm) as he personally rode into the fight.

Despite the ambush, the veteran “boys from Maine” did not break. “The 2nd Maine boys chased the retreating enemy cavalry into Courthouse Square,” as one account describes. In vicious close-quarters combat amid Marianna’s streets, the Union troopers gradually gained the upper hand. Among them was Sergeant Edward H. Cushman of Company M, a 21-year-old from Sumner, Maine who found himself in a literal shootout worthy of a Wild West tale. Sgt. Cushman had dismounted near St. Luke’s Episcopal Church when multiple armed home guards fired at him from behind tombstones and a fence in the churchyard. Cushman, armed with a Spencer repeating carbine (seven shots) and a revolver, coolly returned fire. According to a Maine newspaper report, he fired at the muzzle flashes of his hidden foes, causing the rebels to drop their guns and flee after each shot. As one enemy continued firing from behind a monument, Cushman pretended to be out of ammo; when the Confederate stepped out, Cushman dropped him with a well-aimed shot.

Lieutenant Colonel Andrew B. Spurling of the 2nd Maine Cavalry was a fearless leader during the Florida raids. He commanded the Union cavalry column in the Marianna raid of September 1864 and later earned the Medal of Honor for heroism in Alabama.

Moments later, Sgt. Cushman and Captain John M. Lincoln of Company D charged around the corner of the church and came face-to-face with a pocket of militiamen. The two Maine men — Cushman wielding his carbine and revolver, Capt. Lincoln brandishing a revolver in each hand — fell upon the startled home guards “shooting many of them down before they had time to reload”. At least 27 Confederates were captured in this fierce clash at the churchyard. During the melee, Cushman was hit in the left thigh, but kept fighting. Moments later, a fleeing militiaman suddenly turned and fired at close range, striking Cushman’s other thigh. In what one might call Cushman’s personal “high noon” moment, he also fired – both men hit their mark, and the Confederate fell mortally wounded even as Cushman collapsed from his own wounds. Bleeding from both legs, Sgt. Cushman was carried to safety by his comrades as the fight ended. Captain Lincoln survived unscathed, revolvers smoking.

By late afternoon, the Battle of Marianna was over – a Union victory at the cost of heavy casualties among the defenders. The 2nd Maine Cavalry had several men killed or wounded in the fray, in addition to those captured in earlier skirmishes. (Among the fallen were Privates Silas Campbell and Thomas A. Davis of the 2nd Maine, both “killed outright” in the streets of Mariannasites.rootsweb.com.) The Federals seized about 100 prisoners (including civilians) and destroyed Confederate supplies. However, the fight was bloody for its size. General Asboth, badly wounded, had to be taken back to Pensacola and saw no further field command. For the 2nd Maine Cavalry, Marianna was their fiercest engagement of the war – sometimes called the “Florida’s Alamo” due to the close and desperate nature of the combat.

Cunning Raids and Daring Adventures in Late 1864

After Marianna, Lt. Col. Andrew Spurling took over active command with Asboth injured. Spurling proved to be an audacious cavalry leader, always game for a bold raid. In the following months, the 2nd Maine Cavalry continued striking at Confederate outposts in the region. One particularly unorthodox tactic paid off during an expedition in November 1864. Spurling led 450 men of the 2nd Maine and 1st Florida Cavalry on a mission to destroy a strategic bridge on Pine Barren Creek in Florida. Knowing the element of surprise was crucial, Spurling authorized a risky ruse: a selected vanguard of Union troopers dressed themselves in Confederate uniforms. This mixed group (a few men from each company) was led by Lieutenant Joseph G. Sanders of the 1st Florida Cavalry – a former Confederate officer who had switched sides. In essence, Spurling turned Sanders and these Maine cavalrymen into “bogus Rebels” for the raid.

For three days, the column moved through the pine barrens. According to a letter by Sgt. Frank Pearce of the 2nd Maine, the disguised advance guard made all the difference. Early on the morning of November 17, 1864, near the Pine Barren Creek bridge, Sanders’s camouflaged detachment slipped ahead and surprised the Confederate pickets, who mistook them for fellow soldiers. “Our own Rebels captured the pickets without firing a shot,” Sgt. Pearce reported home. They repeated the trick at several guard posts, quietly seizing all the sentries on duty before they could raise an alarm. By 9 a.m., every outlying picket post had been taken by stealth. Only then did the main Union force rush the Confederate camp near the bridge. When the ruse was finally discovered, Spurling’s troopers charged over the small bridge in a lightning assault. “We chased them in every direction,” Pearce wrote with pride. The result: 38 Confederates (including a lieutenant commanding the camp) were captured, all their horses and weapons seized, and their camp and the crucial bridge were set ablaze. Remarkably, “all this was done without losing a man” in the Union force.

Such success without bloodshed was rare, and Spurling’s report to headquarters glossed over the controversial uniform trick (wearing enemy colors was outside the traditional rules of war). But he did praise the bravery of his men, especially two sergeants in the lead party – one of them identified as Sgt. Frank Butler of the 2nd Maine Cavalry. Butler’s gallantry and the entire deception at Pine Barren Creek showcased the ingenuity of the 2nd Maine and their leaders. For soldiers who had been raw recruits less than a year earlier, they had become savvy veterans willing to take risks.

In December 1864, the regiment undertook another raid, this time into Alabama. Spurling, now commanding a brigade, struck the railroad hub of Pollard, Alabama on December 15, 1864. They skirmished at Bluff Springs and Pollard, capturing the town and tearing up railway tracks. By Christmas, the Maine cavalrymen returned to their Pensacola base. They had earned a bit of rest after months of constant expeditions. Many probably assumed the war was winding down. However, one more major campaign awaited – one that would finally break Confederate resistance in the Gulf region.

The Mobile Campaign and War’s End (1865)

In early 1865, Union General E.R.S. Canby mustered forces for an offensive against Mobile, Alabama, one of the last major Gulf ports still in Confederate hands. The 2nd Maine Cavalry was assigned to Brig. Gen. Joseph Lucas’s cavalry brigade in Major General Steele’s column, which moved from Pensacola north into Alabama. In March 1865, as Steele’s column marched toward Mobile, the 2nd Maine (about 200 men mounted, with additional troopers temporarily without horses fighting on foot) scouted ahead and skirmished with enemy patrols. On March 24, the regiment had a brush with Confederate troops near Evergreen, Alabama. It was here that Lt. Col. Andrew Spurling performed the act of heroism that later earned him the Medal of Honor. Leading a band of scouts in the Alabama backwoods, Spurling encountered three Confederate couriers in the dark. “On that day he captured three ‘Johnnie Rebs’ single-handed, wounding two of them and bringing all three into the Union camp,” a newspaper later recounted. By preventing those Confederates from alerting others to the Union advance, Spurling materially aided the success of the campaign. (Though Spurling performed this valorous feat in March 1865, he did not receive the Medal of Honor for it until decades later, in 1897.)

Proceeding onward, the 2nd Maine Cavalry took part in the siege of Fort Blakely outside Mobile from April 1–9, 1865. Fort Blakely was assaulted and captured on April 9, 1865 – notably, just hours after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, making Blakely one of the last pitched battles of the war. The 2nd Maine joined in the victorious charge that overran Fort Blakely, helping to compel Mobile’s surrender. They entered the city of Mobile on April 12, raising the U.S. flag over a city that had defied Union attacks for four years.

With the war effectively over, the regiment marched to Montgomery, Alabama (the former Confederate capital) later in April. For several months, companies of the 2nd Maine Cavalry served occupation duty across Alabama and western Florida, keeping order as Confederate armies laid down their arms. Finally, the time came to go home. On December 6, 1865, the 2nd Maine Cavalry was mustered out of service at Barrancas, Florida, and shortly thereafter the men returned to Maine. They were formally discharged at Augusta on December 21, 1865, exactly two years from the day the regiment had been officially organized.

Trials off the Battlefield: Sickness in the Ranks

The 2nd Maine Cavalry’s story is not only one of battles won and lost, but also of hardships faced in camp. A striking fact emerges from the records: for every man killed in combat, dozens died from disease. Out of the regiment’s total enrollment, only 10 men were killed or mortally wounded in action, whereas a staggering 334 died of disease during their service. This toll was typical of Civil War regiments, but especially those serving in the Gulf Coast’s disease-ridden environments. Far from Maine’s cool climate, the soldiers had to contend with malaria, dysentery, typhoid, and yellow fever, among other maladies.

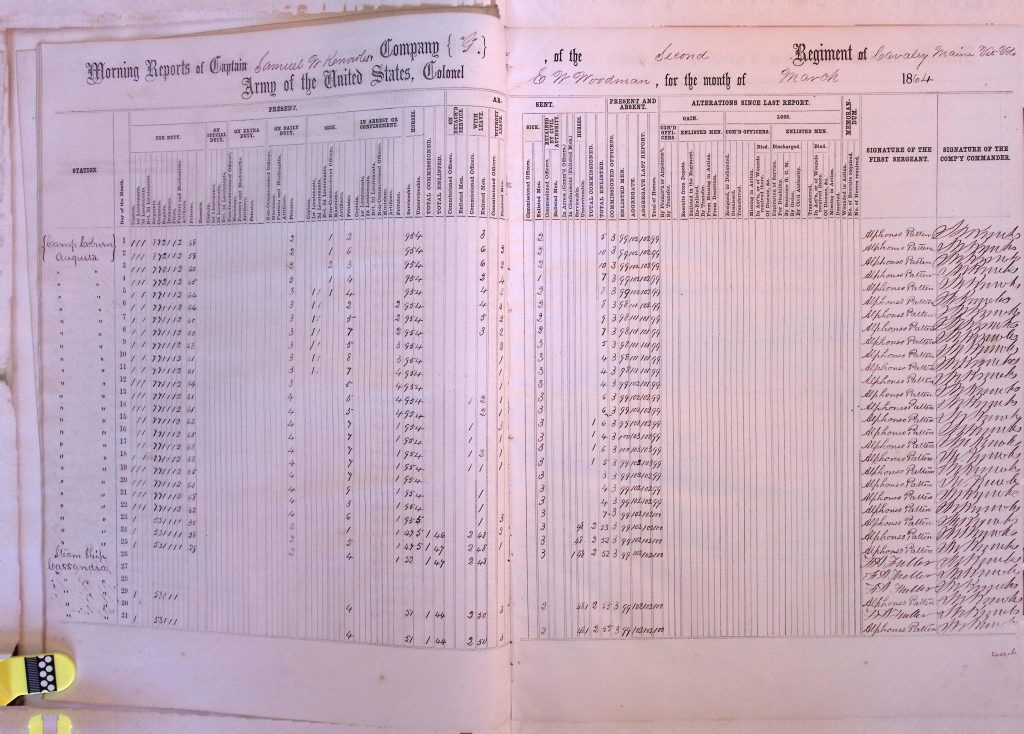

The morning reports preserved in the regiment’s records vividly illustrate the prevalence and impact of sickness. These reports were essentially daily roll calls, noting how many men in each company were present for duty, absent, sick, or hospitalized. By examining morning reports from late 1864 and 1865, one can see the attrition due to illness. For example, one source notes that by December 1, 1864, some companies had virtually no officers fit for duty – sickness had sidelined nearly all of their lieutenants and captains, necessitating reassignmentssites.rootsweb.com. Enlisted men too were often laid up in regimental hospitals in Pensacola or New Orleans. On some days, far more troopers were listed as “sick in quarters” or “absent sick” than were available for combat.

What do these stark numbers mean in human terms? They reflect men like Private Henry F. Nason of Company K (for instance), who might have survived Marianna unscathed only to perish from fever in a New Orleans hospital. They show how disease could cripple a unit as effectively as enemy bullets – especially in an era before antibiotics and effective sanitation. The morning reports, now digitized by the Research Arsenal for Companies A-F and G-M, are a goldmine for historians seeking to understand day-to-day regimental health. They provide granular data, allowing us to track, say, how a yellow fever outbreak in Pensacola in the summer of 1864 caused a sudden spike in sick lists, or how many men were lost to chronic diarrhea during a swampy march. In short, the regiment’s documents highlight that the war’s “unseen” enemy – illness – was constant and devastating.

Treasures in the Regimental Ledgers – Research Arsenal Archives

Fortunately for researchers and descendants today, the 2nd Maine Cavalry’s regimental ledgers have been preserved and digitized (notably by the Research Arsenal project). These primary sources open a window into the daily operations and personnel of the unit. Key ledgers and their importance include:

-

Regimental Descriptive Book – This master volume lists every soldier in the regiment, along with their personal details and service information. It’s essentially a comprehensive directory of the 2nd Maine’s members. Here you can find, for example, that Sgt. Edward H. Cushman was a 21-year-old farmer, or that Private John Doe of Company B enlisted in December 1863 and was mustered out in late 1865. Such basic service details (age, birthplace, enlistment date, promotions, casualties, etc.) are invaluable for genealogists and historians. The descriptive book confirms the names and companies of all soldiers, ensuring that none of these men’s service is forgotten.

-

Company Descriptive Books (A–F and G–M) – In addition to the regimental book, the army kept separate descriptive rolls for each company (A through M, with J typically omitted as a company letter). The 2nd Maine’s records are split into two volumes: one covering Companies A-F and another for G-M. These contain similar details as the regimental book but organized by company. They often include physical descriptions (height, complexion, hair and eye color) and remarks on each soldier. This is where one might learn that a trooper had a scar or was a blacksmith by trade – humanizing details beyond the service numbers.

-

Regimental Letter, Endorsement, and Order Book – This ledger contains copies of official correspondence and orders to and from the regimental headquarters. For example, when Col. Woodman wrote to the Department of the Gulf in June 1864 requesting that a valued sergeant (John C. Phinney of Stockton) be allowed to remain in the 2nd Maine rather than be transferred to another unit, that letter (and the approving endorsement from higher command) was recorded in this book. Such entries reveal the administrative side of the regiment – transfers, disciplinary actions, supply requests, and commendations. They can also mention individual soldiers by name, providing context to personnel changes. The order book portion includes any general or special orders issued at the regimental level (e.g. orders about camp inspections, guard details, or congratulations for a successful raid).

-

Company Order Books (for Cos. A-G and I-M) – Much like the regimental order book, these volumes contain orders and directives at the company level. These might be instructions from the company captain about daily duty assignments, or company-level morning report summaries. They give insight into the day-to-day running of each company. For instance, an entry might note “Company D – detail 5 men for picket duty along the bayou” on a certain date, or record that Corp. James Smith was assigned to clerk duty due to injury.

-

Morning Reports (Companies A-F and G-M) – The morning report books, as discussed, are essentially the daily health and status log of each company. Each morning, the first sergeant noted how many men were present, absent, sick, on detached duty, on furlough, etc. Over time, these reports show the ebb and flow of the regiment’s effective strength. They are crucial for understanding the impact of sickness. For example, if one flips through the morning reports of Company E, 2nd Maine Cav, you might see entries in July 1864 showing multiple men “absent sick in hospital – New Orleans” following the Red River campaign, or a notation in August 1864 of “10 men died this month – fever”. By aggregating this data, one can chart how disease outbreaks coincided with certain campaigns or locations (the Research Arsenal’s digital platform even allows searching these reports by keyword or date). These reports also sometimes mention casualties in action or new recruits joining, making them a day-by-day chronicle of the regiment’s condition.

In sum, the digitized ledgers of the 2nd Maine Cavalry are an arsenal of knowledge (quite fittingly, given the project’s name). They empower anyone interested in the Civil War to dive deep into the micro-history of a single regiment. Whether you’re tracing an ancestor like Corporal William H. Reed (whom a letter home joked should “shoot a Rebel for me”) or analyzing how a unit coped with tropical diseases, these records are indispensable. The fact that they are now text-searchable and accessible online means the stories of the 2nd Maine Cavalry are more reachable than ever.

Conclusion: Legacy of the 2nd Maine Cavalry

The 2nd Maine Cavalry may not be as famous as Gettysburg’s 20th Maine Infantry, but their journey is no less compelling. In just under two years of service, they traversed half a continent – from the far Northeast to the Gulf of Mexico – and adapted from green recruits into seasoned cavalry. They protected New Orleans, rode down remote Florida roads in daring raids, and charged fortifications in Alabama in the war’s final days. They witnessed the chaos of guerrilla warfare, the horror of ambush at Marianna, and the elation of final victory. They also endured long months of illness, boredom, and hard duty, which tested their endurance as much as any battle.

Many individuals of the regiment left their mark. We remember Col. Ephraim “Woodman” struggling to keep his unit staffed as sickness thinned the ranks, Maj. Spurling rallying his men and pulling off audacious feats that read like adventure novels, Sgt. Cushman limping heroically from his personal showdown, and Sgt. Pearce and Sgt. Butler using creativity to bring about a bloodless win. Dozens of other names surface in letters and reports – each a story waiting to be discovered in the archives. The regiment even formed a veterans’ association post-war; in 1873 they held a reunion in Augusta to reminisce about their shared trials.

Today, the legacy of the 2nd Maine Cavalry is preserved both in written history and in those digitized regimental ledgers. The Research Arsenal’s collection makes it possible for us to peek over the shoulder of a company clerk writing the morning report, or a colonel penning a request to headquarters. Through these records, we gain not only facts and figures but a sense of the daily life of the unit – the churn of recruits and casualties, the ever-present concern for health, the commendations for bravery, and even mundane notes about equipment and rations. It’s a reminder that history is often built from such ledgers, as much as from grand narratives.

The 2nd Maine Cavalry’s service in the Civil War illustrates the breadth of the conflict: even far-flung Florida saw determined action, and even late-war regiments raised from scratch could contribute significantly. Their story – informative and inspiring – invites us to appreciate the courage of soldiers who fought in unfamiliar lands under harsh conditions. Whether charging in a “High Noon”-style gunfight or simply answering sick call on a sweltering morning, the men of the 2nd Maine Cavalry did their duty. And thanks to preserved records, we can continue to learn from their experiences 160 years later, ensuring their sacrifices and adventures are not forgotten.

Sources:

-

Maine State Archives, “2nd Maine Cavalry – Adjutant General’s Correspondence” (DigitalMaine repository) – service dates and casualty statisticsdigitalmaine.com.

-

Maine at War blog (Brian F. Swartz), “Shoot out at Marianna” – narrative of the Marianna raid with soldier anecdotesmaineatwar.wordpress.commaineatwar.wordpress.com.

-

Maine Legacy project, Letters to & from Sgt. Pearce – Sgt. Frank Pearce’s November 1864 letter describing Spurling’s disguised raidmainelegacy.commainelegacy.com.

-

Maine Memory Network, Col. C. W. Woodman letter, 1864 – example of regimental correspondence about soldier transfersmainememory.netmainememory.net.

-

The West Florida War (Rootsweb archival excerpt) – names of 2nd Maine Cav soldiers killed at Mariannasites.rootsweb.com.

-

Research Arsenal Digital Archive – Digitized Regimental Ledgers of the 2nd Maine Cavalry (Descriptive Books, Order Books, Morning Reports).