Hearts in the Midst of Battle: Valentine’s Day During the Civil War

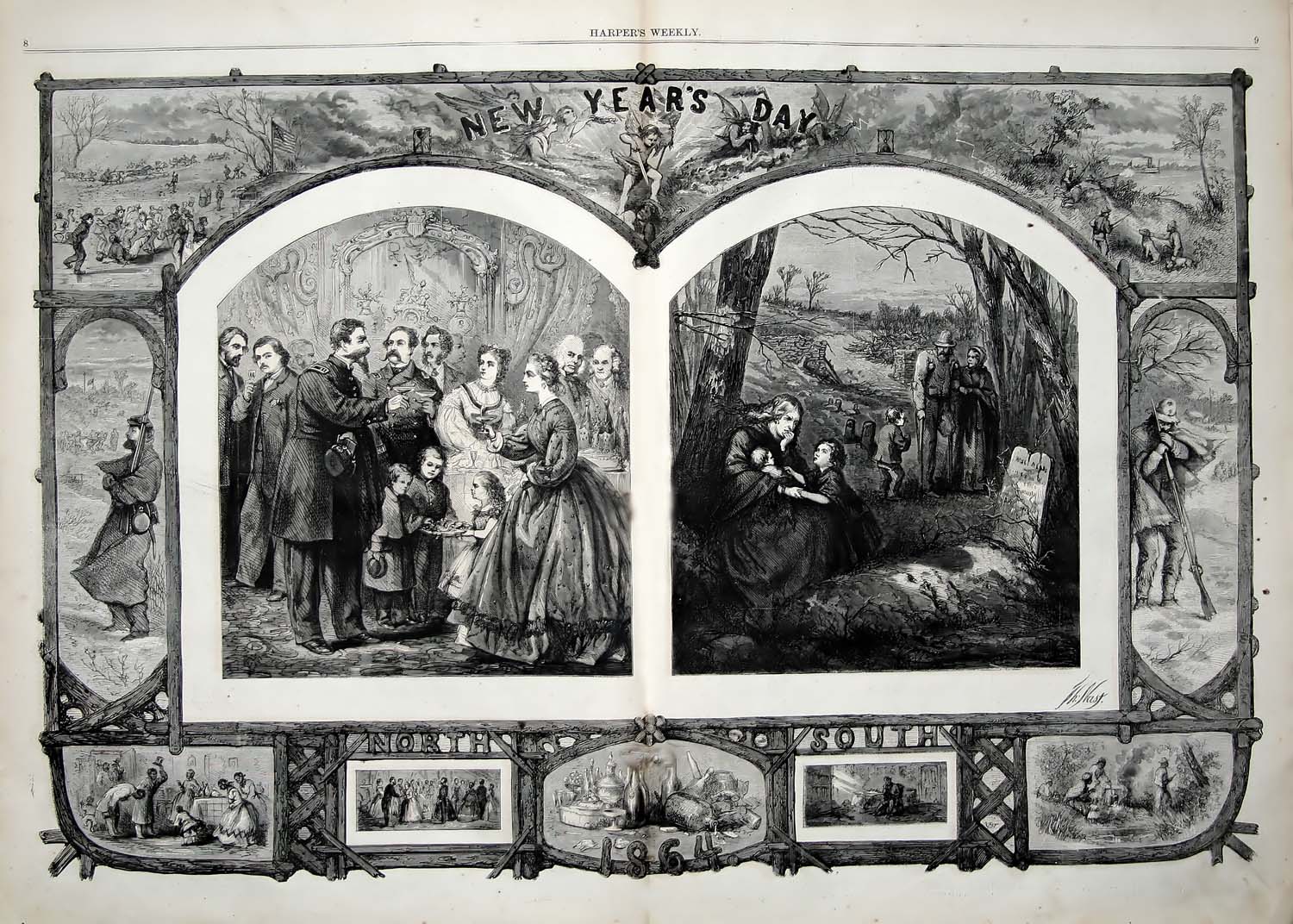

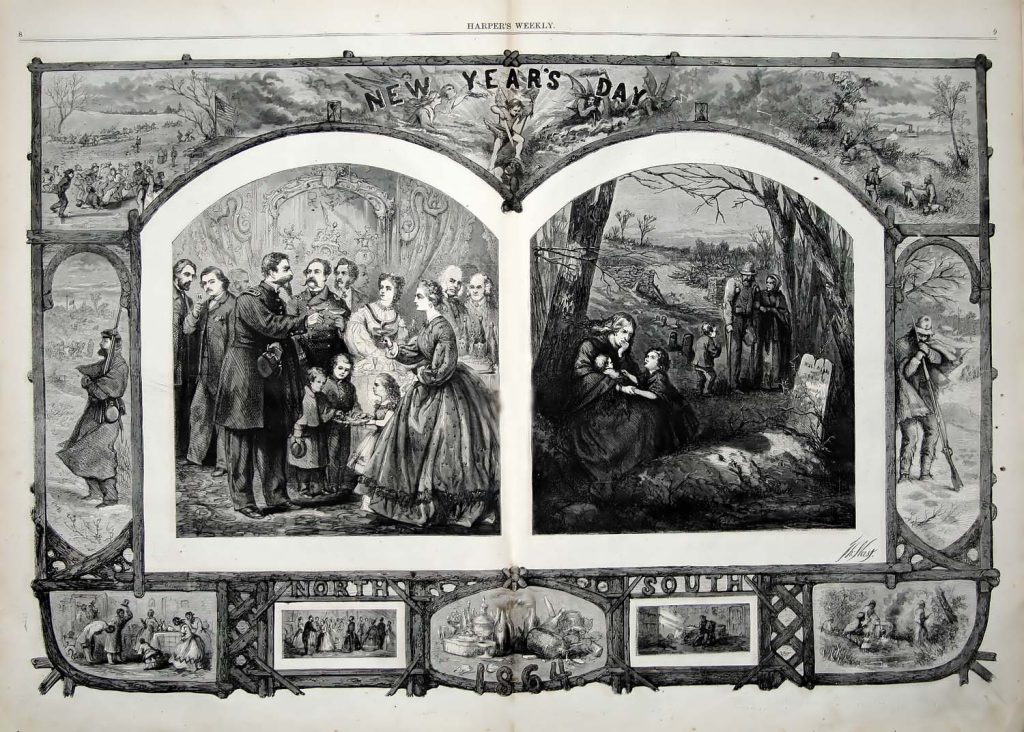

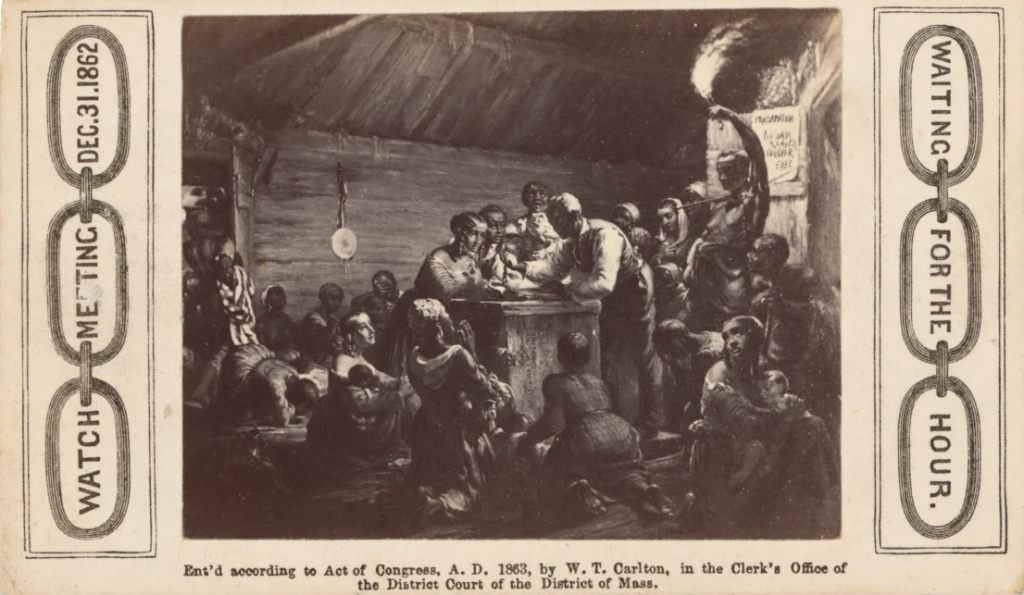

There’s a powerful image that lingers in many American minds each February: couples holding hands, whispering “be mine” as hearts and candies fill the stores. But what did Valentine’s Day look like in the 1860s, when the nation was torn in two and hundreds of thousands of soldiers were scattered across battlefields far from home? For countless families, lovers, wives, and sweethearts, the holiday’s traditional celebration was colored by separation, fear, heartbreak—and, in some cases, remarkable expressions of love that survive to this day.

The Civil War did not erase Valentine’s Day; it transformed it. In fact, newspapers in both the North and South reminded readers that February 14 was near, much like modern ads highlight holidays now. One rural Ohio paper declared, as February approached, “We are reminded that Valentine Day is approaching. Tuesday next, the 14th inst., is set aside as the carnival of lovers,” and cheekily noted that “it is said the birds choose their mates on that day.” Even under the shadow of war, the rituals of love remained compelling enough to merit space on the printed page. (The Journal of the Civil War Era)

Valentines on the Home Front

On the home front, Americans eagerly anticipated valentines. Commercial Valentine producers actively pitched their wares, especially to women whose beloveds were away serving. Advertisements from 1862 urged buyers not to “forget your soldier lovers” and to “Keep their courage up with a rousing Valentine,” available in prices from six cents to five dollars. The American Valentine Company in New York sold “soldiers’ valentine packets,” while vendors in Washington, D.C., offered “comic valentines and beautiful valentine cards in fancy envelopes.” (The Journal of the Civil War Era)

Picture a bookstore window in February 1862: the display filled with cards “large and varied enough to suit the tastes of all,” sitting beside public notices about wounded veterans seeking pensions and announcements of troop movements. This juxtaposition—romance and war news side by side—captures how life and love persisted even amid chaos. (The Journal of the Civil War Era)

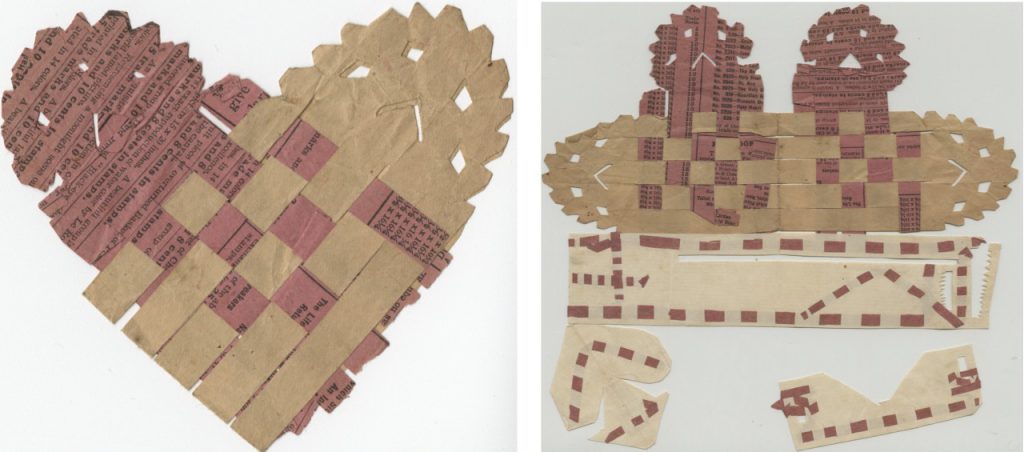

Yet Valentine’s Day in this era wasn’t only about pretty cards. Commercial cards coexisted with deeply personal, handmade expressions of affection. On both sides of the conflict, lovers crafted messages and tokens infused with longing, devotion, and the real fear of loss.

Soldiering and Sentiment

Many soldiers lacked access to commercial cards, so they turned to their own pens—or knives—to craft valentines. In one of the most haunting surviving examples of Civil War romance, Confederate soldier Robert H. King created a delicate paper heart for his wife, Louiza, using only a penknife and scraps of paper. The heart appears perforated with random holes, but when opened and studied more closely, the design reveals two figures seated opposite each other, weeping. (The Journal of the Civil War Era)

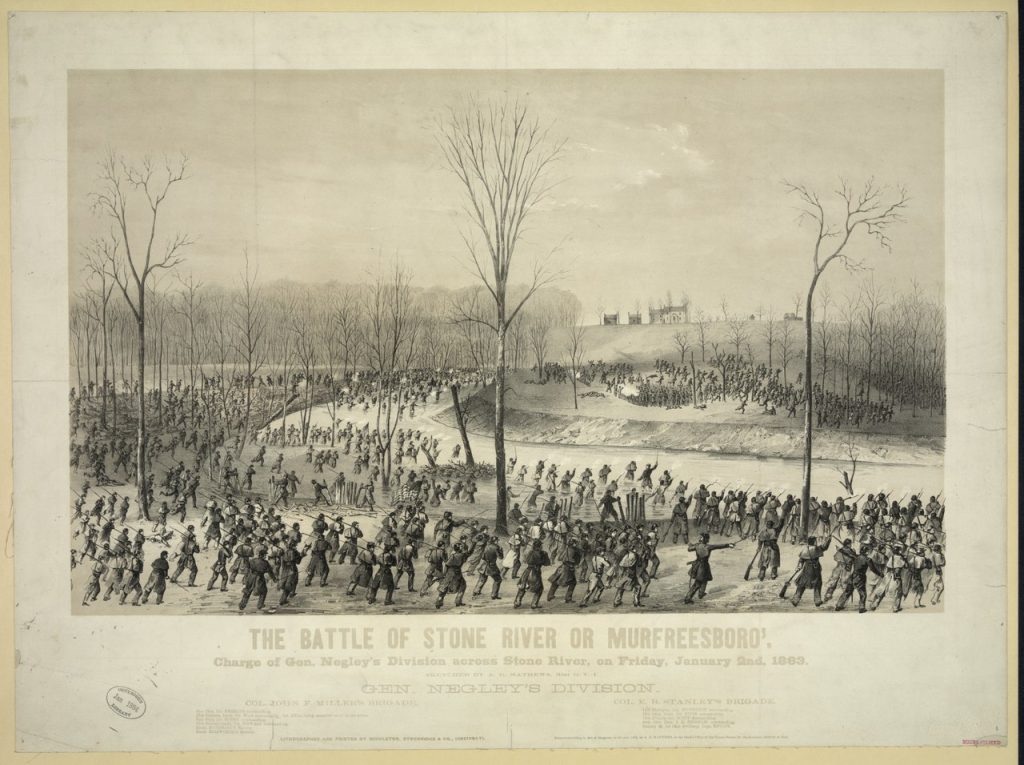

This wasn’t mere symbolism; it was a heartfelt expression of separation. In a letter dated November 8, 1861, King wrote to Louiza, “it panes my hart to think of leaven you all,” signing the letter, as many soldiers did, “yours til death.” Tragically, that vow proved bitterly accurate: Robert H. King died of typhoid fever near Petersburg, Virginia, in April 1863. Louiza treasured the paper heart for the rest of her life. (The Journal of the Civil War Era)

King’s handwritten words and painstakingly crafted heart remind us that Valentine’s Day in 1863 could be an exercise in longing as much as celebration: letters carried love across miles of battlefield and barbed wire, binding spirits together when flesh and bone could not.

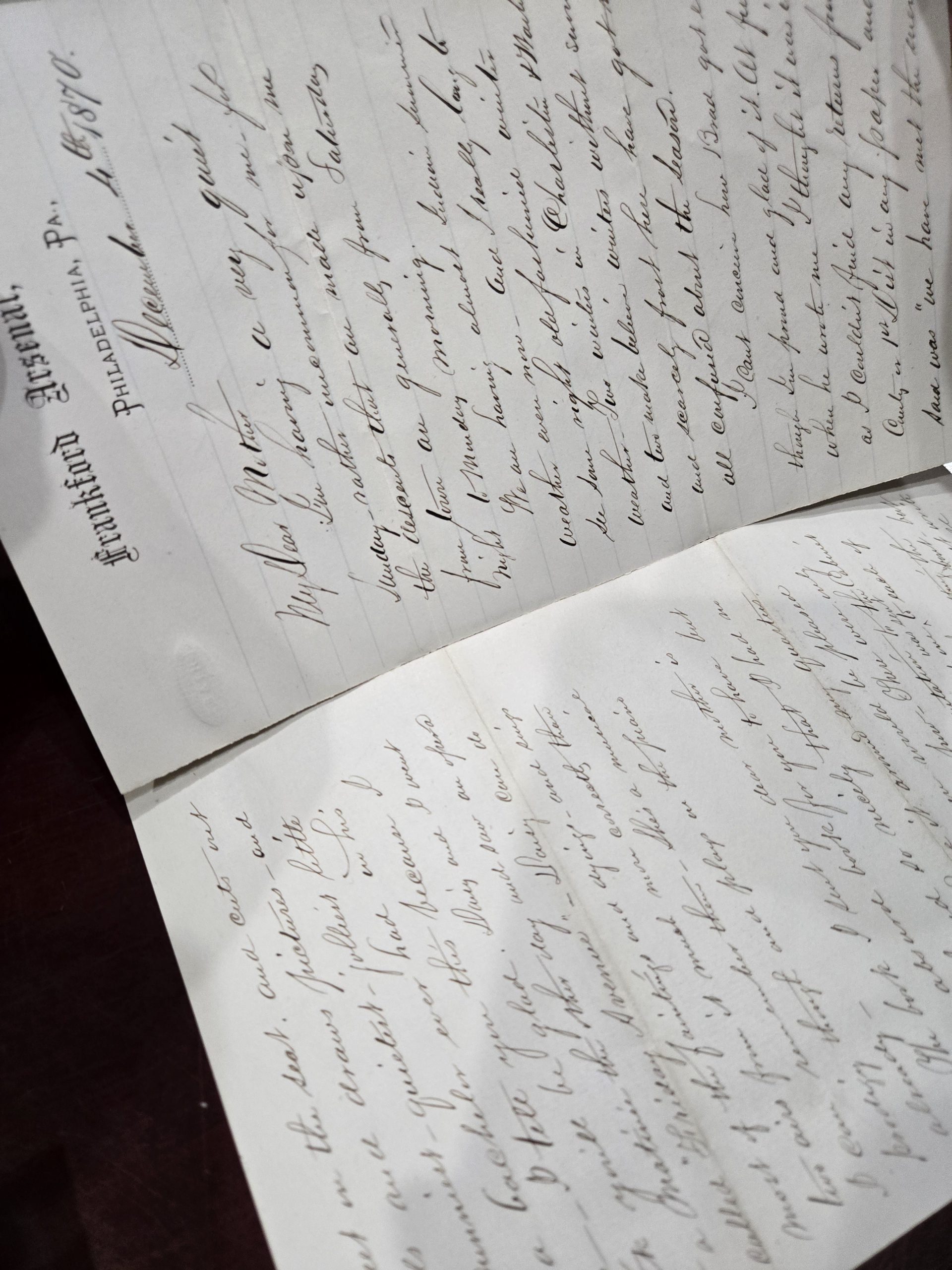

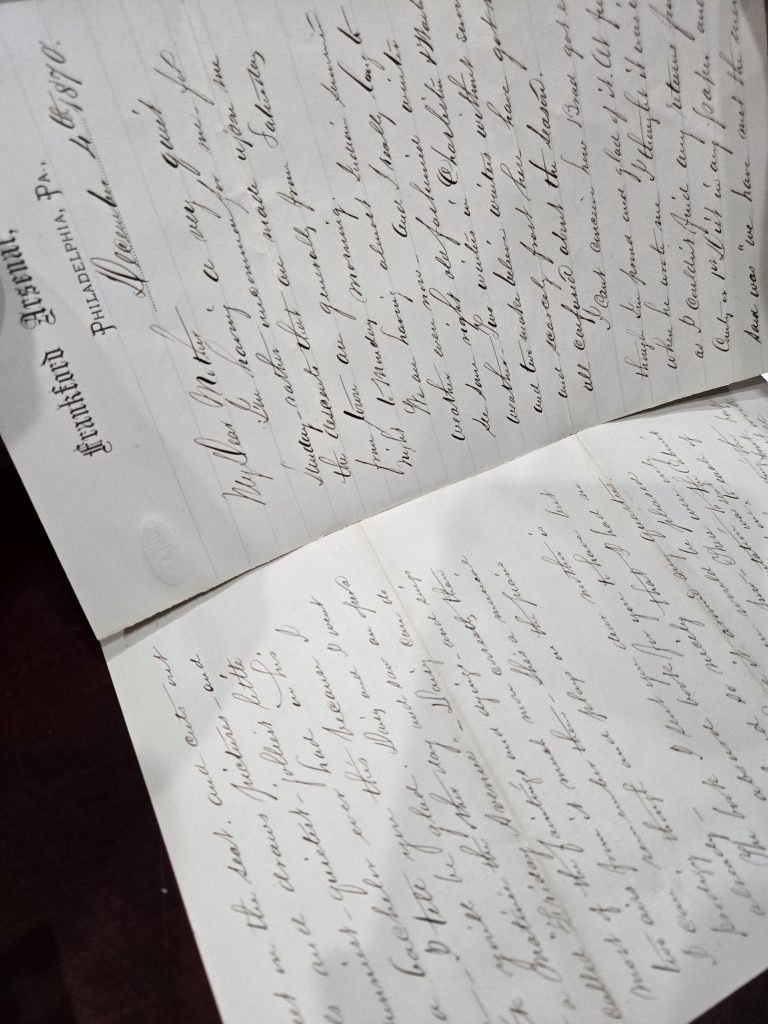

Below is an example of a friendly Valentine taken from letter written by Dexter Buell, Co. B, 27th Regt. New York State Volunteers to his friend Robert Allee:

“Bob, today is Valentine’s Day. I wish I had one to send to you. Bob, the boys are all busy making finger rings and pipes,&c. to fetch home with them. We make them out of laurel roots. I am making a pipe and ring for you out of laurel root. Bob, I guess you had a pretty nice time with the girls. I have not seen a girl in so long I forgot how they look.”

The following is an excerpt of a letter from Josiah Cole Reed of the 94th Ohio Infantry to Elizabeth “Lizzie” Freeman, written February 26, 1865:

“On glancing at this letter I see so many omissions and mistakes that I am afraid to read it over for fear I will become so disgusted with it as to tear it up and then I would have to write another. I shall expect an answer to this in two weeks. Shall I be disappointed? Of course your convenience will not be overlooked. I only me(an) that I hope it will be convenient for you to answer immediately, that I may receive a good, long, sweet letter in two weeks.

Received three valentines but none worth anything

I remain as ever your true friend, — J. Reed”

Lines of Poetry Across the Lines

Not all expressions took the form of art objects. Some soldiers poured their emotions into verse. In 1863 a Virginian soldier penned verses to a woman named Mollie Lyne, capturing a soldier’s conflicted heart:

Mid all the trials and toils of war,

The clash of arms, the cannon’s roar,

The many scenes of desolation and strife,

And varying fortunes which surround this life.

Naught else disturbs me, half so much,

As the nightly visions which haunt my couch.

But why should I not be happy?

Ah! Methinks that thou canst tell,

Thou hast me bound, as if by spell,

I love thee Mollie, with all my heart. (HistoryNet)

Elsewhere, Private Joseph C. Morris of the Phillips Legion Cavalry wrote to his beloved Sylvanie Bremond on February 14, 1865:

“Moments appear days to me, and day an age…when I cannot behold your beloved face….Why have we passion? If upon the first development of their genuine tenderness they must be curbed and checked by the arbitrary rules of war.” (HistoryNet)

These words, polished under the pressure of a brutal war, transcend commercial sentiment. They reflect longing intensified by the real possibility that a lover might never return.

Comic, Satirical, and Patriotic Valentines

On the other end of the emotional spectrum were comic and satirical valentines that used humor to process the absurdity and sorrow of their times. Some Civil War valentines, preserved in collections like the Library Company of Philadelphia, poke fun at soldiers’ appearances, behaviors, and reputations. One verse reads:

“Mr. Rifleman…If you think that with you I would wed…Like a turnip, my dear, is your head.

So with you I’ll never wed.” (Civil War Monitor)

“Mr. Rifleman, but I would be a flat, / If you think that with you I would wed: / Cheeks put out your eyes — nose turn’d to the skies— / Like a turnip, my dear, is your head. / One like you is enough for a bed, / So with you I’ll never wed.”

Others lampooned Copperheads—Northern Democrats critical of the war effort—branding them unworthy of affection. Still others embraced patriotic sentiment, promising devotion to “my valiant son of Mars” who defended the flag. (Civil War Monitor)

These valentines reveal that love and war could coexist with biting wit and public commentary. Americans did not silence humor or satire because of conflict; they redirected it into familiar cultural forms.

Lasting Legacies of Civil War Valentines

Valentine’s Day in the Civil War era reminds us that love persists even in the darkest times. The war’s devastation—the sight of dead battlefields, grieving families, and endless hardship—did not diminish the human need to express affection. Instead, it made those expressions all the more poignant.

Commercial cards flourished alongside handmade creations. Soldiers’ letters survive as testaments to yearning and devotion. Printed verses and home-crafted hearts became vessels of emotion, capable of bridging battle lines and years of separation. In writings like those of Robert H. King and Private Morris, we see what it meant to love someone across the divide of war—and to risk having that love be all you have left.

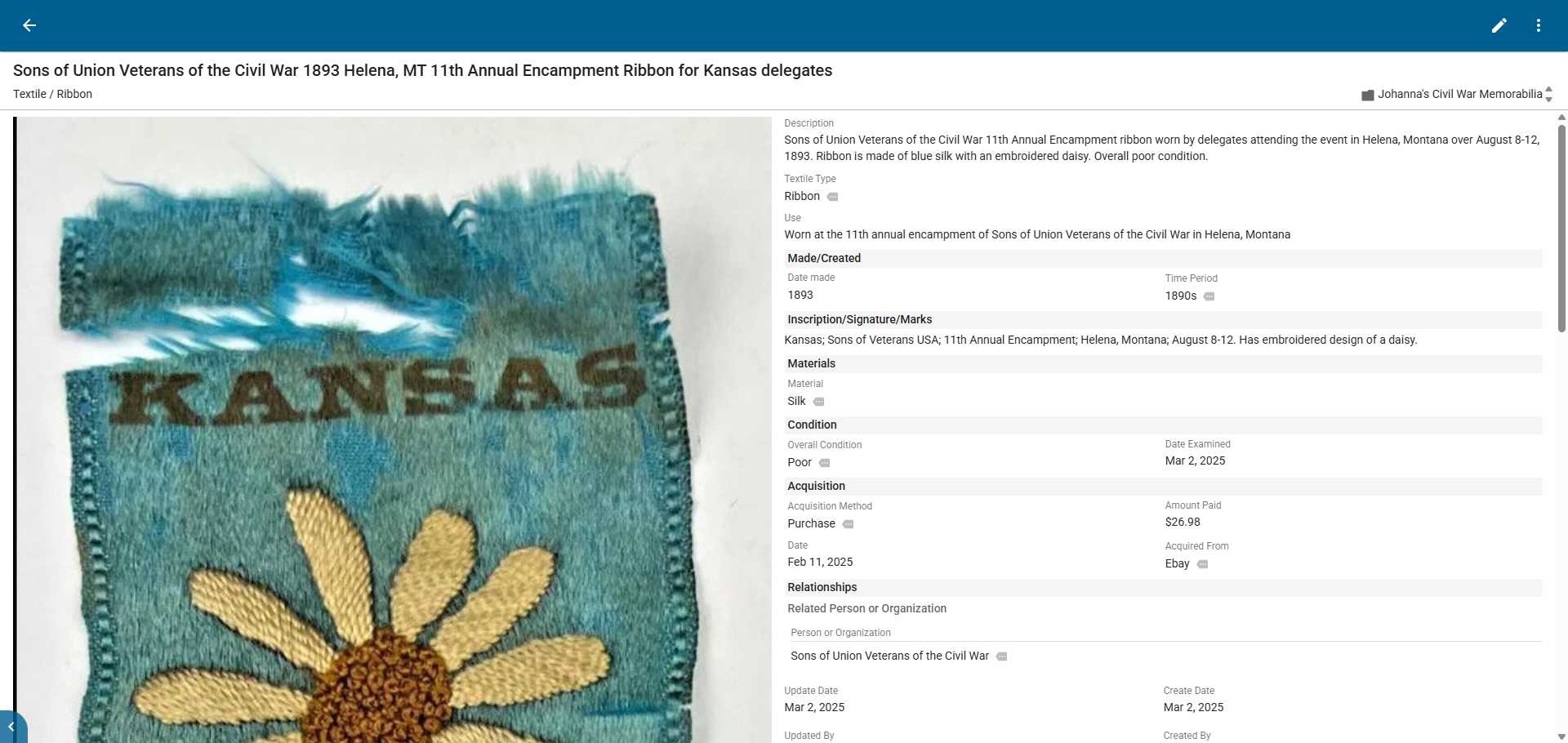

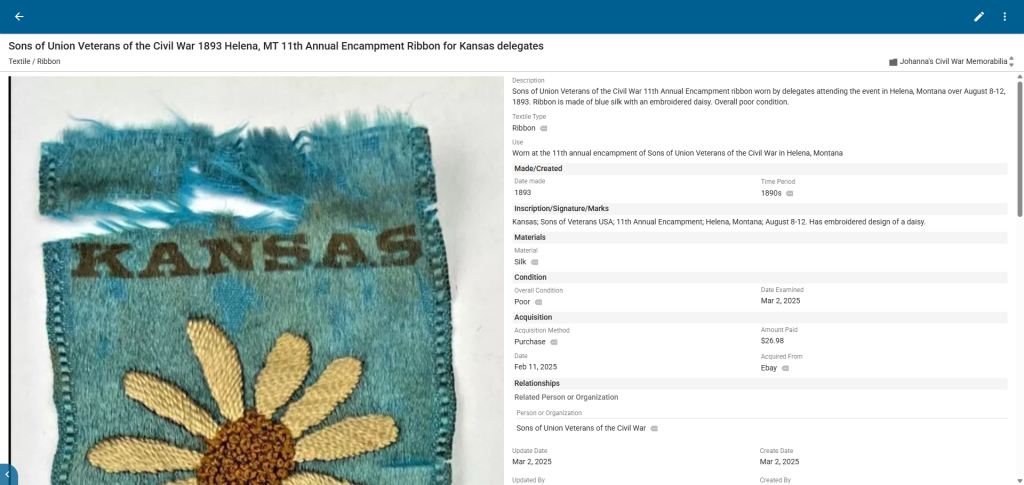

Civil War valentines and love letters are an excellent reminder that behind all of the photographs, archives, and accoutrements Civil War collectors treasure, those items all belonged to real human beings, who just like us, fell in love. Unfortunately, many of them, like Robert H. Kind, did not get a happily ever after with their loved one.

Sources

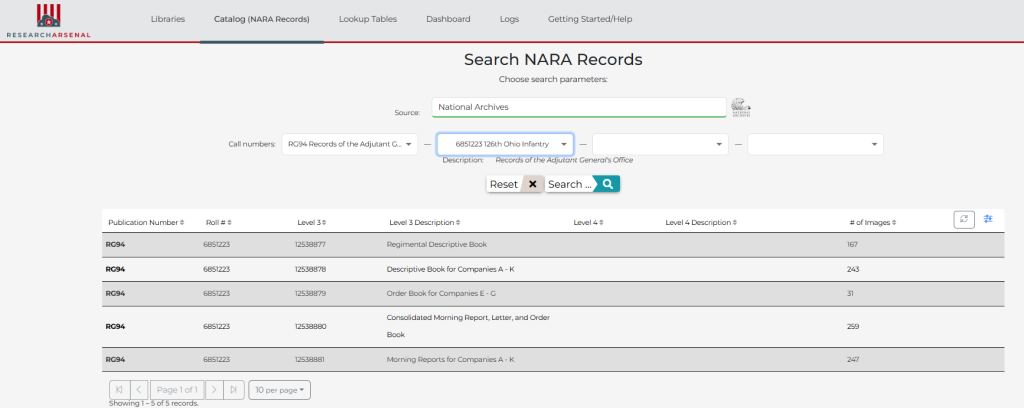

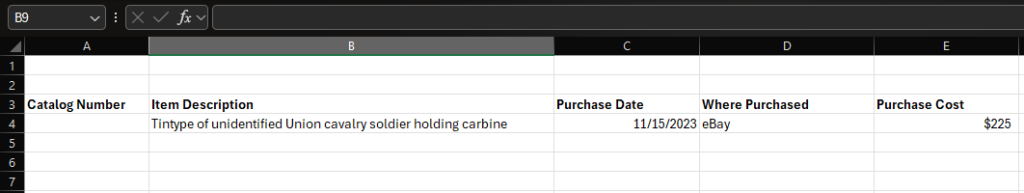

- Research Arsenal –Read Dexter Buell’s LetterRead Josiah Reed’s Letter

- Civil War Monitor – Civil War Valentines (Library Company of Philadelphia examples) (Civil War Monitor)

- Angela Esco Elder – “Don’t Forget your Soldier Lovers!” A Story of Civil War Valentines (The Journal of the Civil War Era)

- Ruth Ann Coski – Hearts at War: Valentine’s Day in the Civil War (HistoryNet)