Why You Need to Inventory Your Collection

Keeping track of your collection is one of the most important things you can do as a collector. We all know how it starts: You are going through life minding your own business when suddenly you get bitten by the collector bug. Now you find yourself scouring eBay, Facebook Marketplace, flea markets, antique stores, garage sales, and greasy dumpsters for your latest finds. Don’t worry, there’s no shame in that. Although if you’re a regular dumpster diver I’d definitely make sure that all your shots are current….

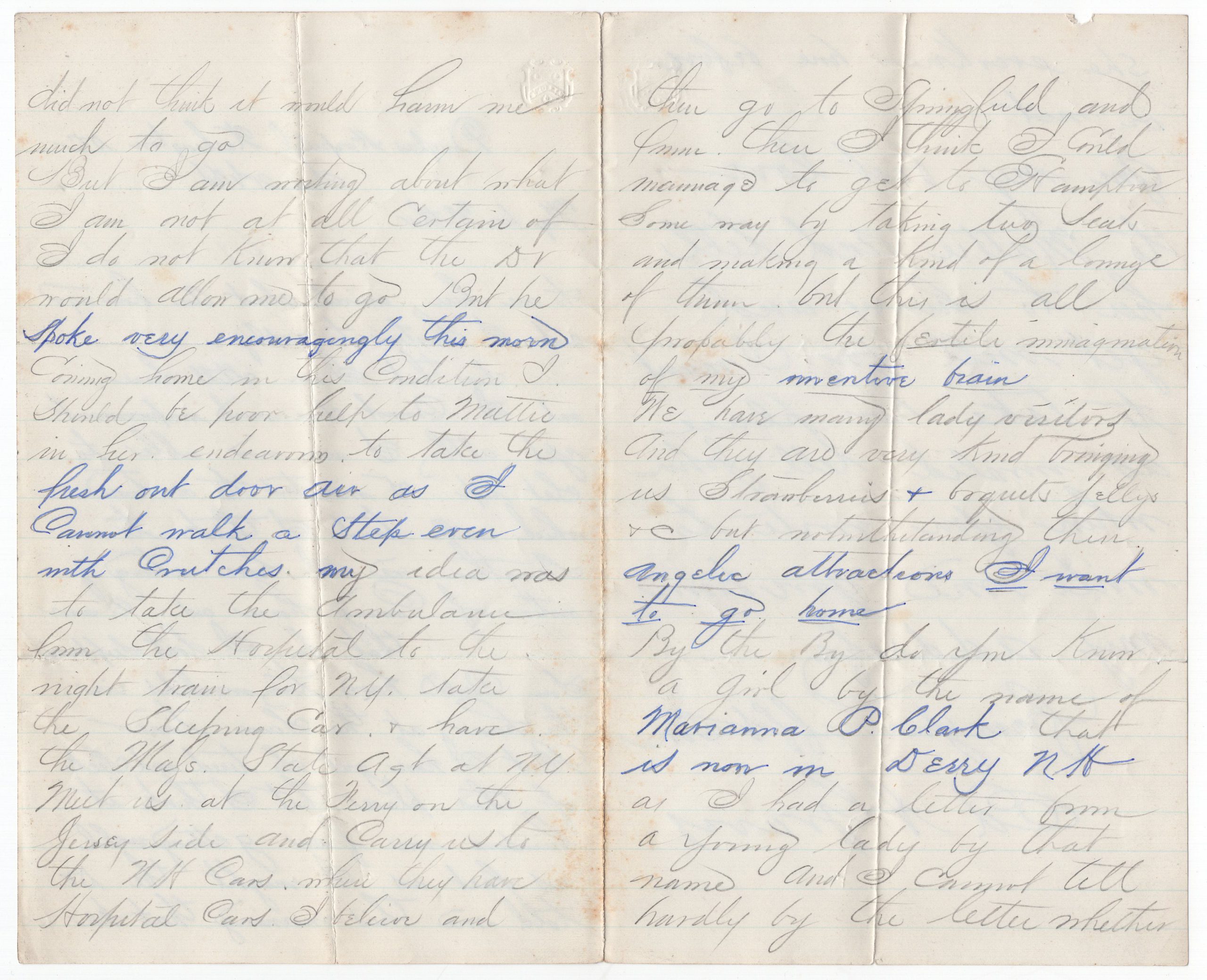

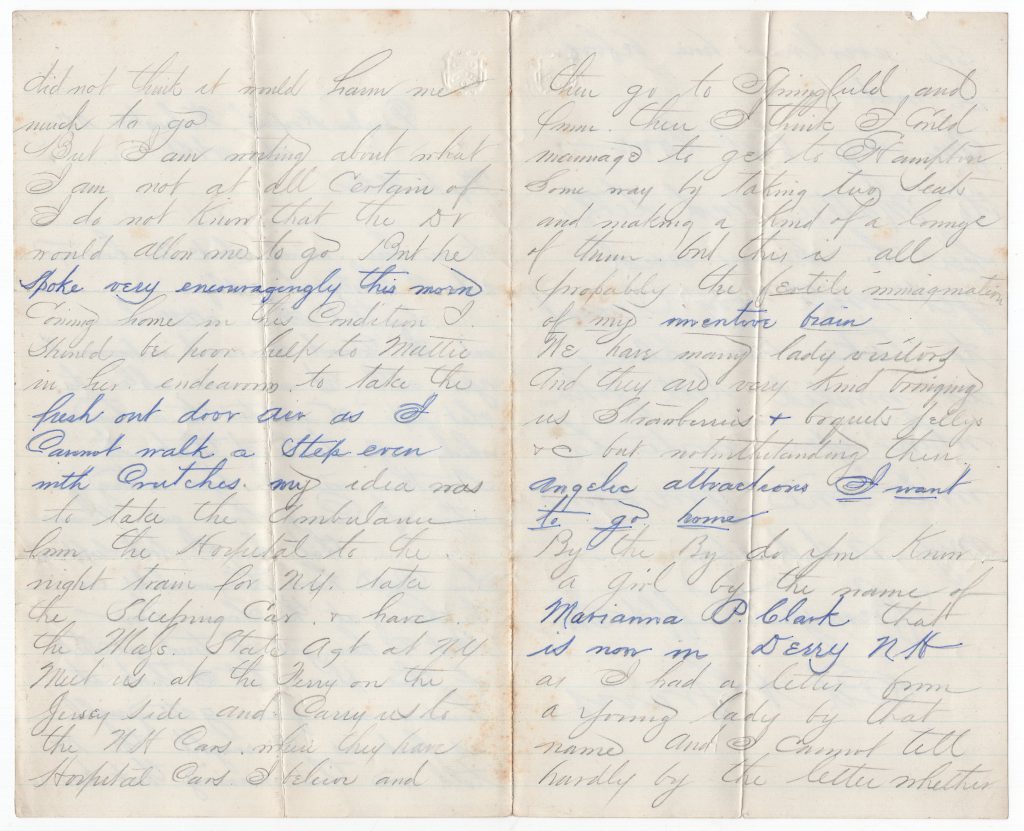

Once the collector bug has struck, you may find your new collection quickly spiraling out of control with more and more additions. Whether it’s a plethora of general Civil War memorabilia, a hefty photographic collection, firearms, buttons, badges, or ribbons, it can get overwhelming fast. Are all of these finds still on display? Or has that beautiful new sharpshooter tintype you found on your latest dumpster diving trip (hey, it could happen!) taken center stage on the mantel and relegated those other old CDVs to a drawer or a binder? Do you have all of the information of where you got these things, who you got them from, what the significance of them is, where they are stored, what you paid for them, who’s in the picture, and more, written down somewhere, or is it all in your noggin? If it’s the latter, it’s high time to start getting this information down on something concrete.

And if any of you are out there saying, “But I can remember all this! I know all this information in my head!” I’m going to tell you right now, STOP. Once your collection ends up with more than a few things, you won’t be able to remember the exact date you got something, the exact price you paid, the name of the person who sold it to you, the random funny story the seller told you about the person it used to belong to, etc. That information will fade. It’s a simple fact of life. The second issue with this mentality is what if something happens to you? We all know someone who has passed unexpectedly or has been severely debilitated by a stroke or freak accident. We all think it won’t happen to us, but the truth of the matter is that it absolutely can. One last thing to consider is what happens to all of your stuff when you pass on? Are your kids taking it? Do they have the encyclopedic knowledge of your collection that you do? Will it be sold? Does your family have the encyclopedic knowledge of your collection to sell it for a fair price? We all love those deals we find where someone is selling something that they have no idea the actual significance or value of. We’ve all made scores like that, but that’s probably not something any of us would like to see happen to our collections.

How Can I Keep Track of My Collection?

At this point, you may be asking, “Well, this is wonderful information, but what can I do?” I’m so glad you asked! May I present to you, the idea of (drumroll) CATALOGING!” You may say, “But I’m not a museum! I don’t need that!” Well, my friend, once you’ve crossed the line into a large collection, you may as well be a museum. You’re in the big leagues now and you’re going to need to start using some sort of catalog system to track and store information about your collection. This is not as overwhelming as it may seem, and chances are, many of you are already doing something like this.

Over the next few blog posts, I’m going to walk you through creating and using a museum catalog system. I will take you through the basics of creating a trinomial numbering system, how to number your items (spoiler alert, it’s not with ballpoint pen. Didn’t you read last week’s article?), enter them into a database, and store your collection. The goal of all of this is to ensure that your collection itself and the information associated with your collection, all stays together in perpetuity. It’s frustrating to think that we may own an unidentified photo that maybe just one or two owners back, was actually identified, but the information was lost when the collection was parceled out on eBay. This happens far more often than I like to think about. Having all this information together in a single database will help alleviate those concerns. Not to mention, this also becomes a fantastic way to track your collection for insurance and appraisal purposes.

As someone who has worked in museums, ran museums, designed exhibits, and served on museum boards for the past 17 years, there are a lot of museum practices that would be of tremendous benefit for private collectors. A catalog system is high on that list because the value of keeping information with artifacts is priceless. So, pull out your notebooks for next week’s post as we dive into this. This is also a wonderful time to assess your collection and really take the time to inventory it, even just on a cursory level. How many items do you have? Do you know exactly which items are in which boxes for storage? Which items are on display? Can you pop quiz yourself on where, when, how and for how much you got each item? And for those of you who have a catalog system in place, how does that system work? Is there anything it’s not keeping track of that you wish it was? We’re going to go over all of this in the coming weeks and I sincerely hope that the information in these upcoming articles will help you find a system that works perfectly for you!

In the meantime, hop over to the Research Arsenal and look through the database to see what sort of data points it tracks. Then take a look at the Library of Congress (or any other inventoried database) and get a feel for how these sites organize information and what they keep track of.