The First Ship Sunk by a Naval Mine: The USS Cairo

This week marks the 163rd anniversary of the sinking of the gunboat USS Cairo. Remarkably, a sinking with no loss of life. The Cairo also holds the distinction of being the first ship sunk by a naval mine (torpedo was the term used at the time).

The Birth of an Ironclad — USS Cairo

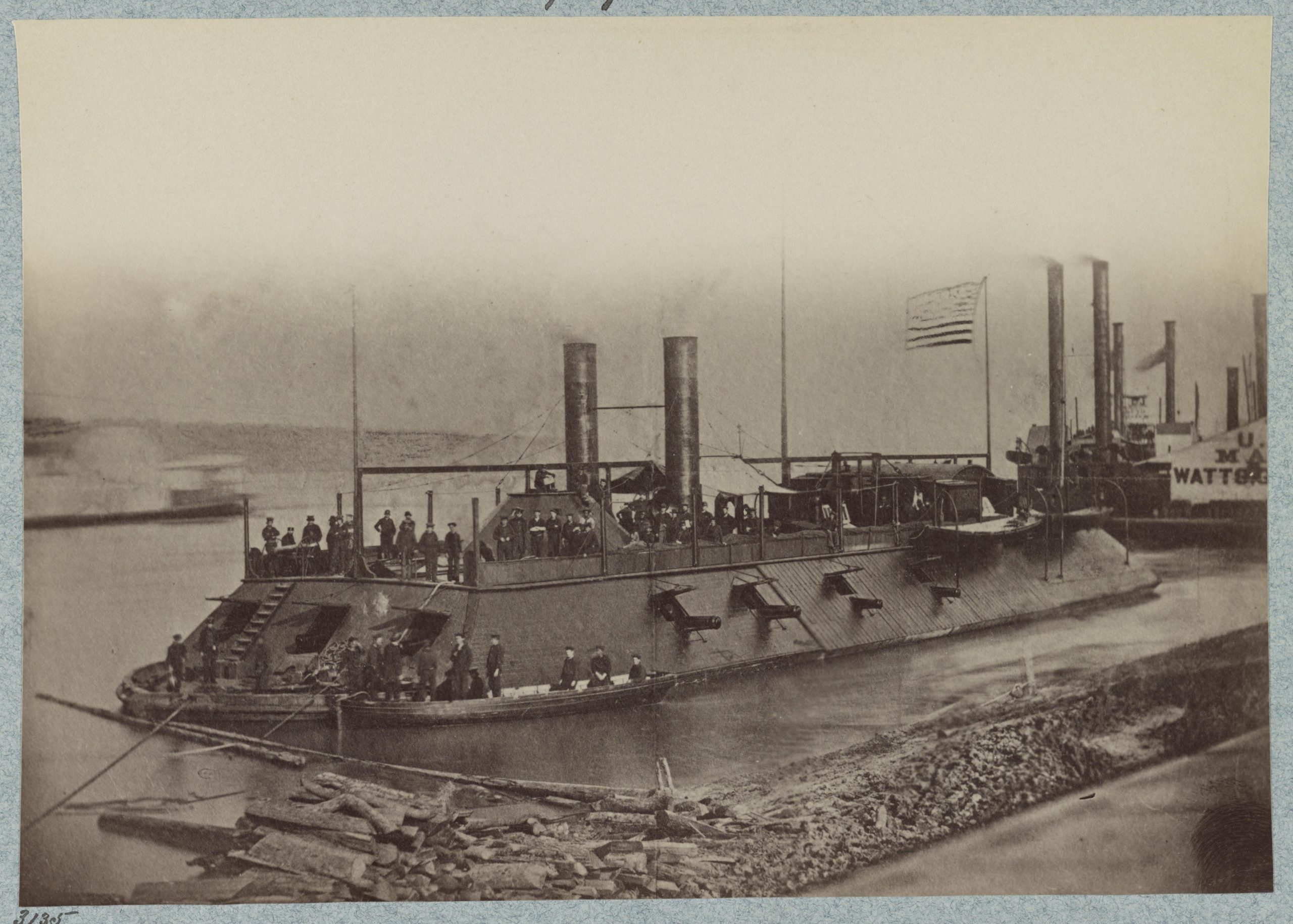

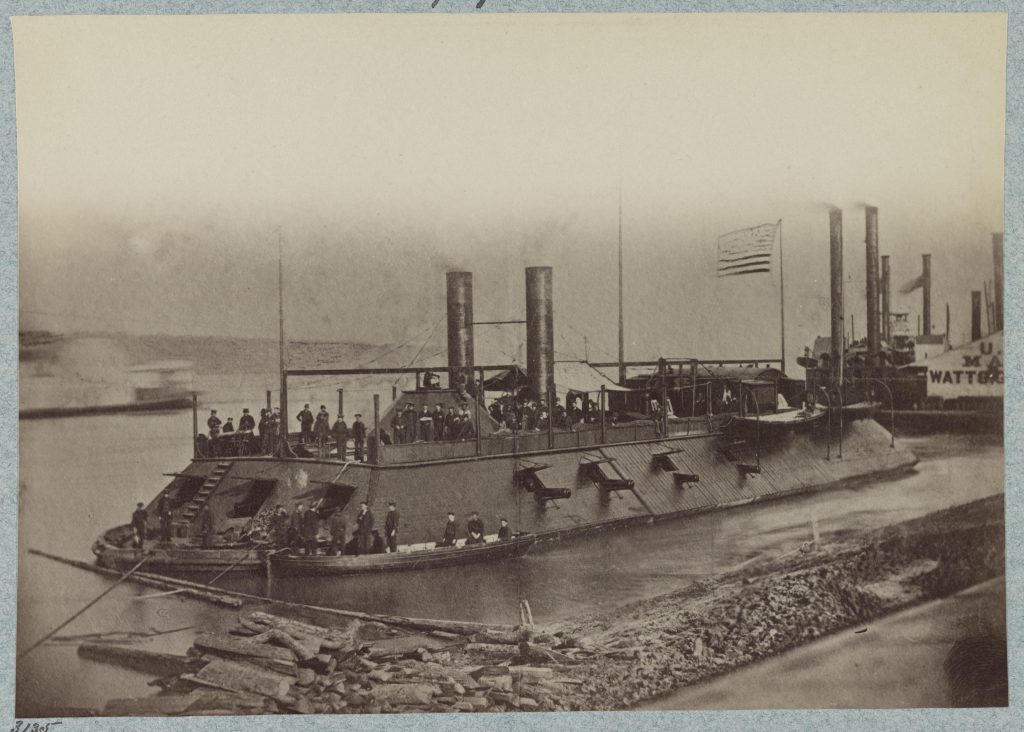

In 1861, as the Civil War erupted, the Union moved to exploit its control of the Mississippi River and its tributaries. Built by James Eads and Company in Mound City, Illinois, the Cairo was the lead ship of the seven-vessel “City-class” of casemate ironclads commissioned for riverine warfare. She measured 175 feet in length, drew only 6 feet of water (making her ideal for shallow rivers), and under her steam-engine and paddlewheel propulsion could manage a modest 4 knots. Manned by a crew of approximately 251 officers and enlisted men, the Cairo was designed to carry heavy armament behind thick iron armor and bring Union naval power inland.

Originally part of the Union Army’s Western Gunboat Flotilla, the Cairo was transferred to the U.S. Navy on October 1, 1862.

Wartime Service: From Forts to Rivers

Shortly after her commissioning, Cairo saw action alongside Union forces in several key operations. In February 1862, she helped occupy Clarksville and Nashville, Tennessee — crucial early moves in asserting Union control over the Tennessee River. In the spring she took part in the reduction of Fort Pillow, which fell to Union forces in early June. On June 6, 1862, Cairo joined a flotilla of Union warships in a naval battle off Memphis, Tennessee, defeating a similar Confederate flotilla and helping secure the city for the Union.

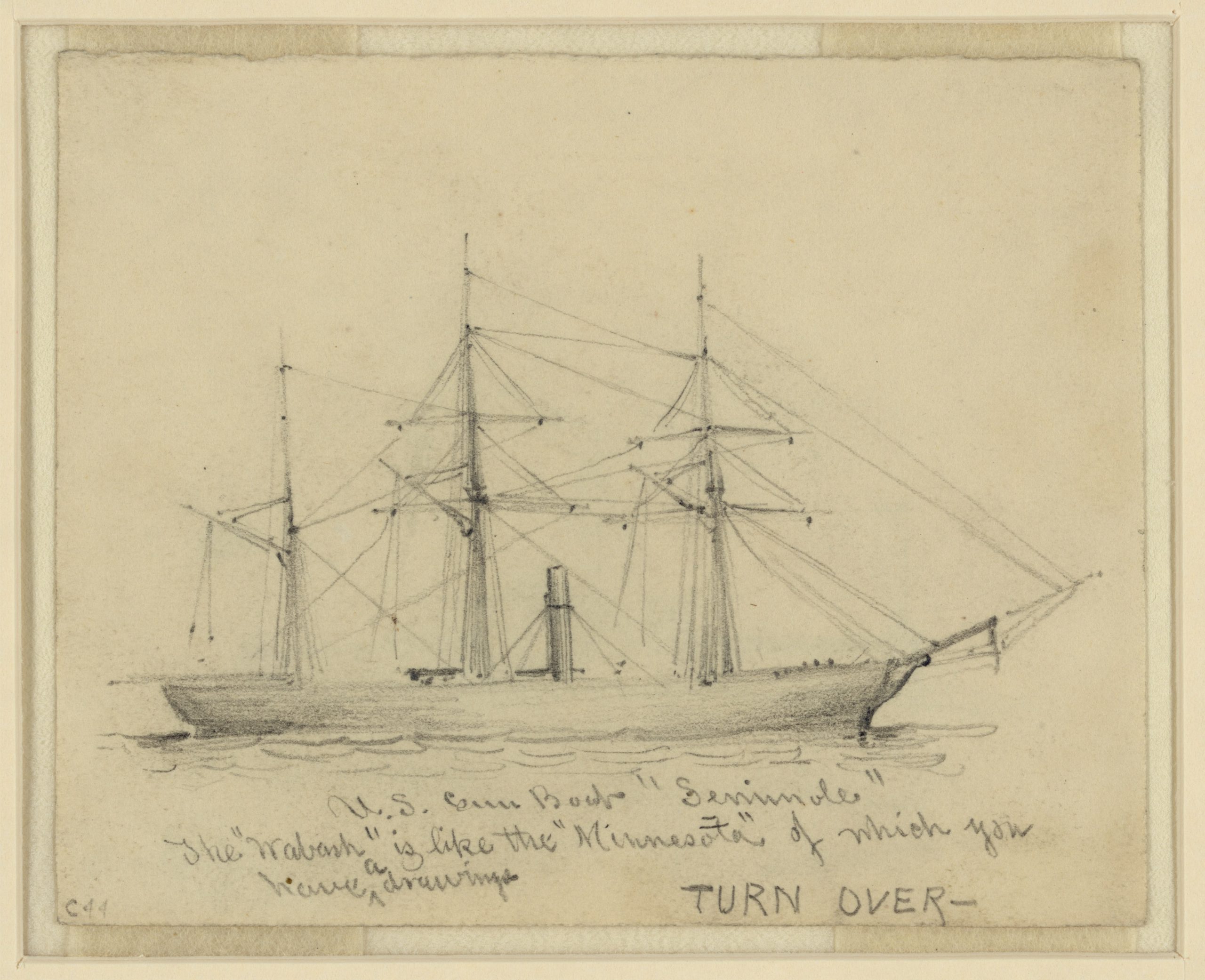

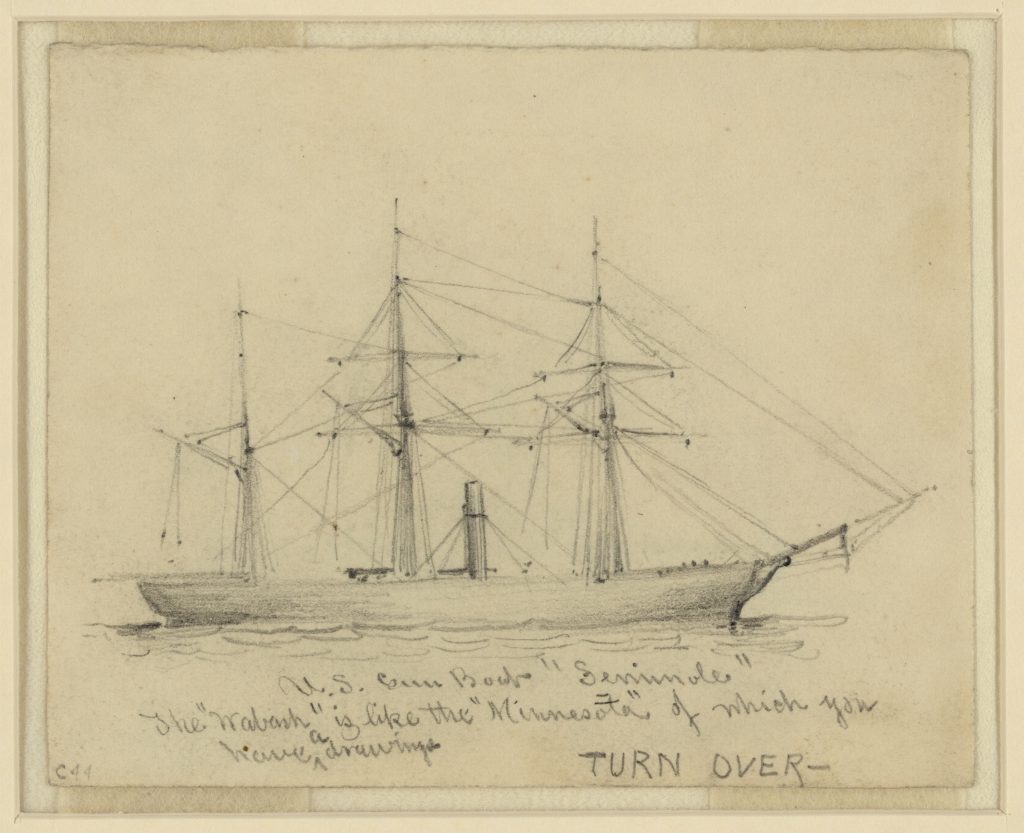

By late November 1862, the Cairo had shifted to operations along the Yazoo River as part of the Yazoo Pass Expedition — a campaign aimed at clearing the river of Confederate defenses to prepare for an attack on Haines Bluff, north of Vicksburg, Mississippi.

A Sudden End — First Ship Lost to a Naval Mine

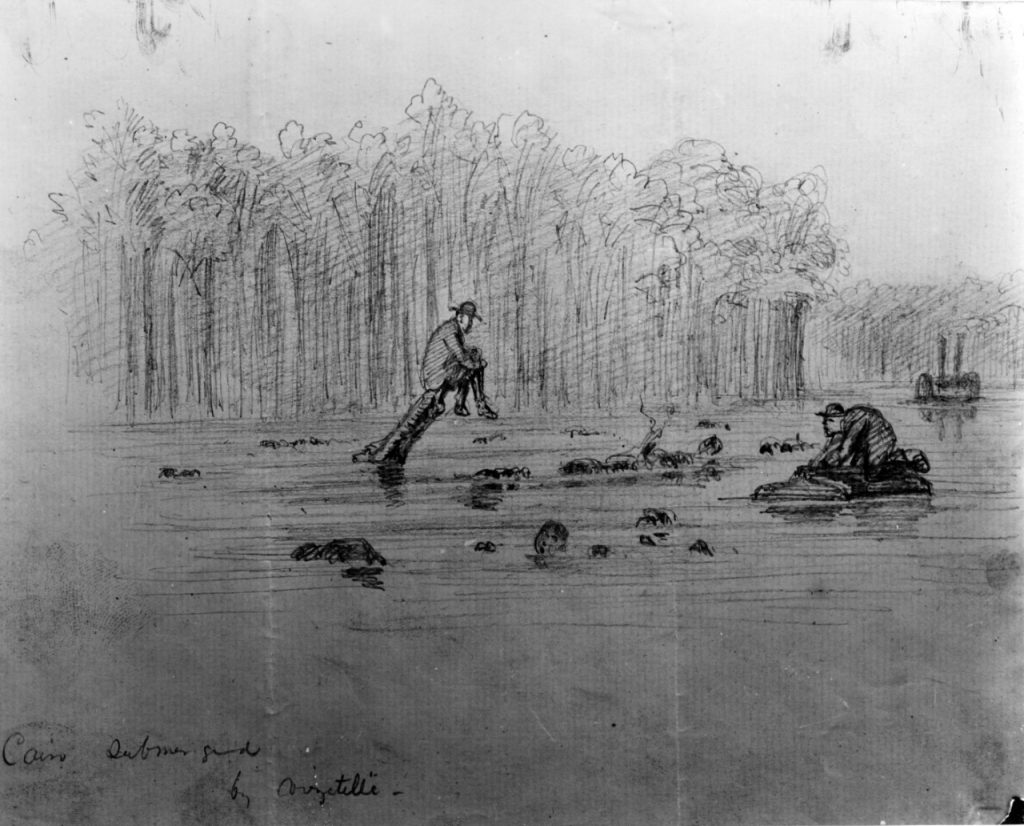

On December 12, 1862, under the command of Thomas O. Selfridge, Jr., Cairo was helping to sweep the Yazoo for underwater “torpedoes” — the term then used for what we now call naval mines. Selfridge saw another gunboat, the Marmora firing and assumed that it was under attack by Confederate sharpshooters. Selfridge ordered the Cairo forward and deployed small boats to assist the Marmora. However, the Marmora was not under attack and was firing its guns to detonate a mine it had discovered. Shortly after this maneuver an explosion rocked the Cairo. According to Ensign Walter Fentress of the Marmora, he “saw her anchor thrown up several feet into the air.”

Unfortunately, the Cairo struck an electrically detonated mine placed by Confederate forces who were hidden along the riverbank. Two explosions ripped into her hull, creating gaping breaches.

In just twelve minutes, Cairo sank into approximately 36 feet of water. Miraculously, there was no loss of life. This tragic event marked a grim milestone: the Cairo became the first armored warship in history to be sunk by a remotely detonated mine.

Lost and Forgotten — Then Rediscovered

For over a century, the Cairo lay buried beneath silt and mud at the bottom of the Yazoo River — effectively preserved by the oxygen-poor sediment.

In 1956, historian Edwin C. Bearss (alongside local historians Don Jacks and Warren Grabau) used civil-war–era maps, a magnetic compass, and crude iron probes to locate the wreck. Their efforts paid off — by 1959 divers retrieved an armored port cover that confirmed the identity of the ironclad.

Salvage operations began in earnest in 1960. Over the next several years, many artifacts were recovered: cannons, personal items, naval equipment — all preserved by the river mud. By 1964 the hull was raised (cut into three sections to prevent further disintegration) and placed on barges; eventually, the components and artifacts were transported to a shipyard in Pascagoula, Mississippi for conservation.

Resurrection as a Museum — Legacy and Public History

In 1972, Congress authorized the National Park Service (NPS) to accept ownership of the Cairo, paving the way for her restoration and display. By 1977 the restored ironclad was reassembled on a concrete foundation near the Vicksburg National Cemetery and opened to the public at Vicksburg National Military Park in Mississippi.

Visitors to the park can walk aboard the Cairo and peer into her history: inside the adjacent museum are hundreds of artifacts recovered from the wreck — personal effects of sailors, tools, weapons, even meal utensils — offering a rare, intimate window into life aboard a Civil War ironclad.

The Cairo is one of only three surviving Civil War-era gunboats, and she stands as a testament both to early industrial naval design and to the human stories of those who served in the “brown-water” navy that fought the war on America’s inland rivers.

Why USS Cairo Still Matters

The story of the USS Cairo resonates on multiple levels. As a technological artifact, she embodies a pivotal shift in naval warfare: the transition from wooden sailing ships to armored, steam-powered vessels adapted for river combat. As a casualty, she marks a grim innovation in warfare — the use of underwater mines to sink a warship. As a rediscovered relic, she provides historians and the public a tangible link to the lived reality of Civil War sailors. And as a museum, she educates and reminds us of the human cost and ingenuity of that conflict.

Standing on her deck today — surrounded by recovered artifacts and the Mississippi-river air — one can almost hear the creak of timbers, the hiss of steam, the shouted orders of anxious sailors. The Cairo remains more than a wreck: she is a bridge between past and present, a silent storyteller of courage, tragedy, and legacy.

Sources

“USS Cairo.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Cairo.

“The USS Cairo Story.” Visit Vicksburg, https://www.visitvicksburg.com/blog/uss-cairo-story/.

“Thomas O. Selfridge, Jr. – The Life and Career of an Early American Naval Officer.” Naval Historical Foundation, https://navyhistory.org/2013/12/thomas-o-selfridge-jr.

“USS Cairo.” Naval History and Heritage Command, https://www.history.navy.mil/our-collections/photography/us-navy-ships/alphabetical-listing/c/uss-cairo0.html.

“U.S.S. Cairo Gunboat and Museum.” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/vick/u-s-s-cairo-gunboat.htm.