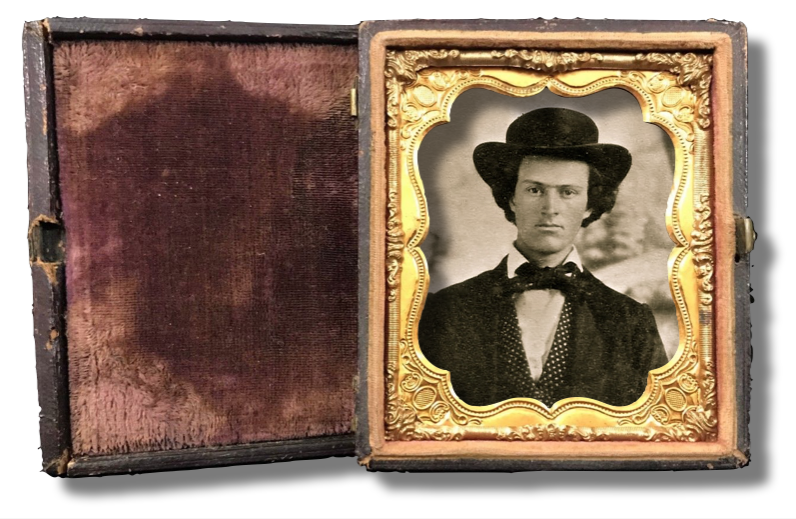

William Fish enlisted in Company C of the 11th New Hampshire Infantry at the age of nineteen. He was the son of John Blaney Fish and Mary Holmes (Barrett) Fish. William Fish enlisted on August 8, 1862. His older brother, John Linzey Fish, was a private in the 1st New Hampshire Light Artillery Battery, having enlisted in September, 1861.

The first letter in our collection was written by William Fish on August 26, 1862 while his regiment was still in Concord, New Hampshire. The space they occupied had recently been vacated by the 9th New Hampshire Infantry which proved to be quite a boon for the men of the 11th New Hampshire Infantry.

“We keep a guard around our camp now. I have to take my turn. The Ninth Regiment left quite a lot of trash behind. We went to work and cleaned out the tent we occupy and most everyone found something. I found a first rate new three-bladed penknife, five cents in change, ink, a bottle of olive oil, and a few other things. One fellow found a dollar bill & Reub Smith found a knife and twenty-six cents. Gil [Smith] found a dirk knife. Quite a number found money. We have first rate living and plenty of it. Ten of us were detailed to go over to the city in the Quartermaster store and hoist up a lot of goods from the lower story to the one above and I had a chance to see our uniforms. It is to be dark blue pants [and] dark overcoats. I understand we are to have no dress coats. I did not see any there.”

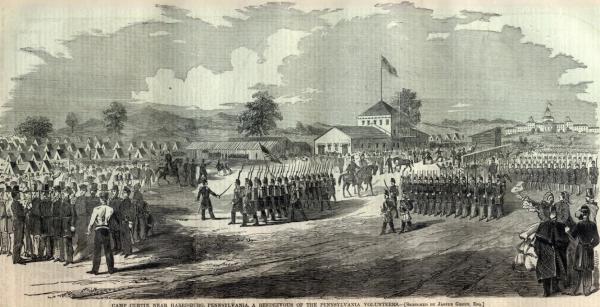

William Fish in General Casey’s Division

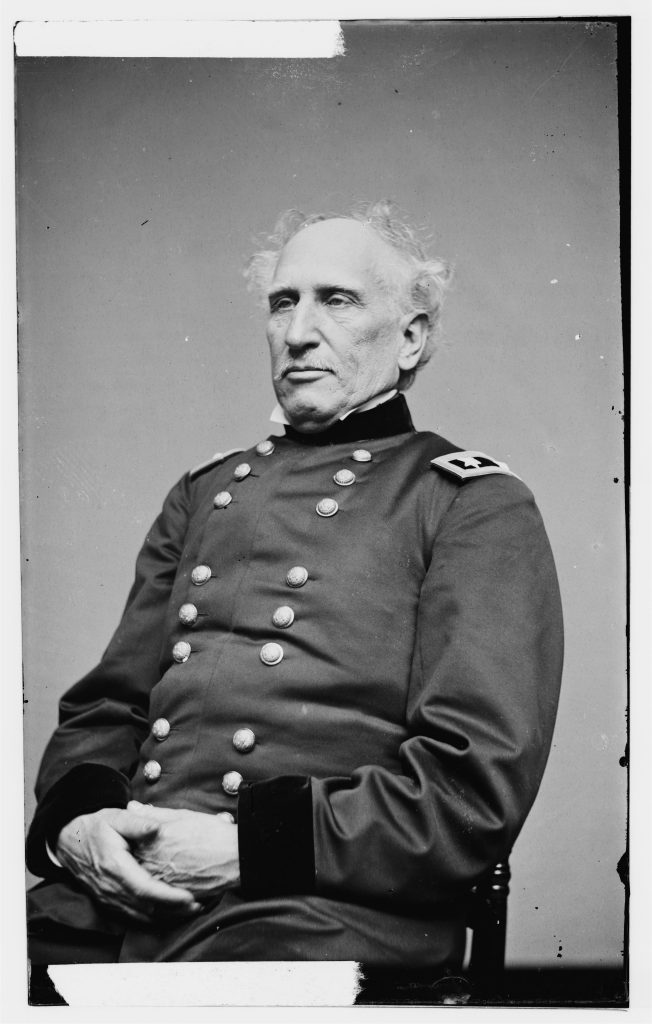

William Fish and the 11th New Hampshire Infantry were soon sent south to Camp Chase at Alexandria, Virginia. For the most part, William Fish was occupied with drilling throughout the day. On September 25, 1862, he wrote home about a recent review of their regiment by General Silas Casey, the head of their division.

“We have had two division reviews — one day before yesterday. We are in Gen. Casey’s Division. There were as near as I could learn twelve thousand troops reviewed and a number of batteries. It is a grand sight to see the columns as they pass — to see the bayonets glistening and the steady tread of the men.

Gen. Casey is an old man with gray hair and prominent nose. He wears a beard. There are a great many troops in the vicinity. Take it in the night and look off, the camps present the appearance of a city lit up.”

A few days later, the 11th New Hampshire Infantry moved down to Frederick, Maryland, a less than pleasant journey as William Fish recounted in a letter to his sister, Martha, dated October 2, 1862.

“We came through safe and sound although we were packed like cattle on board a freight train — two cars to each company — part of the men being on top. Along in the middle of the [trip], it set in for a storm and then it was a complete jam to lay down — legs mixed up in every direction. We passed a train of 400 paroled prisoners. We couldn’t get much sleep till we arrived here at four this morning where our company piled into an old barn and laid down on the hay.”

William Fish also added that the rumor around camp was that they would soon be marching under General Ambrose Burnside.

“This is rather a pretty place., I should think full as large as Manchester. We expect orders any time to leave. We shall not probably stop over a day or two at the furthest. It is the talk that we are to take the cars to Sandy Hook to go under Gen. Burnside but I do not think of much more to write.”

In this case, the rumor proved to be correct.

11th New Hampshire Infantry at Pleasant Valley, Maryland

William Fish’s next letter was written on October 14, 1862 once the 11th New Hampshire Infantry had arrived at Pleasant Valley, Maryland. He revealed that the regiment was indeed now under the command of General Ambrose Burnside.

“We are brigaded under Brig. Gen. [Edward] Ferrero in Gen. Burnside’s army of the Ninth Army Corps. We will not probably stop here long though we can not tell.”

The camp location proved to be a fruitful one and William Fish revealed that he was good making use of the local flora, saying “I have been writing with ink made from garget berries which are very plenty here.” Garget berries are more commonly known as pokeberry or “inkberry” and are a poisonous berry that can—as the inkberry name suggests—be used to make ink.

William Fish was also located near his brother, John Fish, though when writing this particular letter he had yet to see him.

“The 9th and 10th [New Hampshire] Regiments are here near us. The centre section under William Chamberlin of the [1st N. H.] Battery were down here last night. They carried two guns to the depot at Sandy Hook and stopped here on their way back. The boys look well. John did not come with them but the boys say he is well.”

Finally, William Fish shared that though there was considerable food growing near the camp, it was risky to try to go after it.

“We have a good chance to wash as a brook runs by the foot of the hill on which we are camped. There is considerable quantities of butternuts, chestnuts, shag barks, and black walnuts though we cannot go far from camp without running the risk of being picked up by the patrol guard and sent to Harpers Ferry to work for twelve days as none of the soldiers are allowed out of the lines of their regiments without they have a pass signed by the Gen. Commanding. This is to pick up stragglers and prevent depredating.”

William Fish at the Siege of Knoxville

William Fish was wounded at the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 13, 1862. His brother, John Fish, was killed on the same day also at the Battle of Fredericksburg. For the period of 1863, part of which time William Fish spent recovering, we do not currently have any letters in our collection, though three are available to view at the New Hampshire Historical Society.

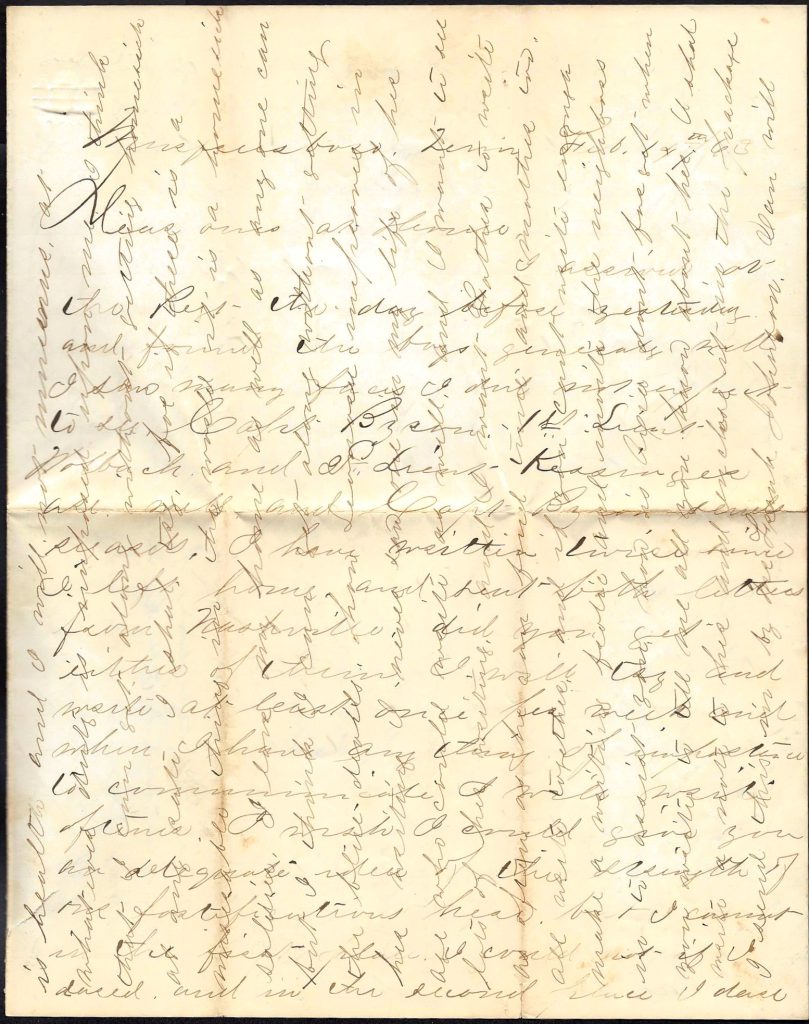

The letters by William Fish resume in the Research Arsenal collection on January 7, 1864, with William Fish writing to his sister after the Siege of Knoxville.

“You must have felt quite anxious concerning me during the time we were besieged in Knoxville by Longstreet. We had no mail communication for three or four weeks and consequently did not write. But now (from all accounts the boot appears to be on the other leg), Grant and Sherman it has said has Longstreet surrounded. I sent you in my last a piece composed by one of the Indiana Battery on Longstreet’s visit to Knoxville. It is represented that he is in a very tight place and cannot get supplies or clothing and his men are deserting in great numbers. Two whole companies came in a day or two ago.”

By this time, William Fish was confident that the war would end soon.

“Fighting is heard out at the front at times. The rebel deserters that come into our lines represent Longstreet’s army as in a terrible condition. They are hard up for shoes, some being barefoot and others in their stocking feet. Our army has been very successful for the past 6 or 8 months and I do not see how the Rebs are going to hold out much longer. The fact is there are whipped if they would only own it.”

On May 6, 1864, William Fish along with two other men from Company C of the 11th New Hampshire Infantry were captured at the Battle of the Wilderness. The men were all sent to Andersonville Prison.

William Fish survived to the end of the war and was released from Andersonville on July 31, 1865. He married Eliza Gage 1869. After Eliza Gage died in 1917, William Fish married Helen L. Ober, who was the widow of John Whipple, a fellow soldier from the 11th New Hampshire Infantry who died at Andersonville.

On August 29, 1936, William Fish died at the age of 93. He was buried at Shawsheen Cemetery in Bedford, Massachusetts.

We’d like to extend a special thanks to William Griffing of Spared & Shared for his work in transcribing and sharing these letters.

To read more of William Fish’s letters, as well as a letter by his brother, John, and access thousands of other Civil War documents, sign up for a Research Arsenal membership.

If you enjoyed this article, check out some of our other featured collections like David Patten of the 35th Illinois Infantry and David Poak of the 30th Illinois Infantry.