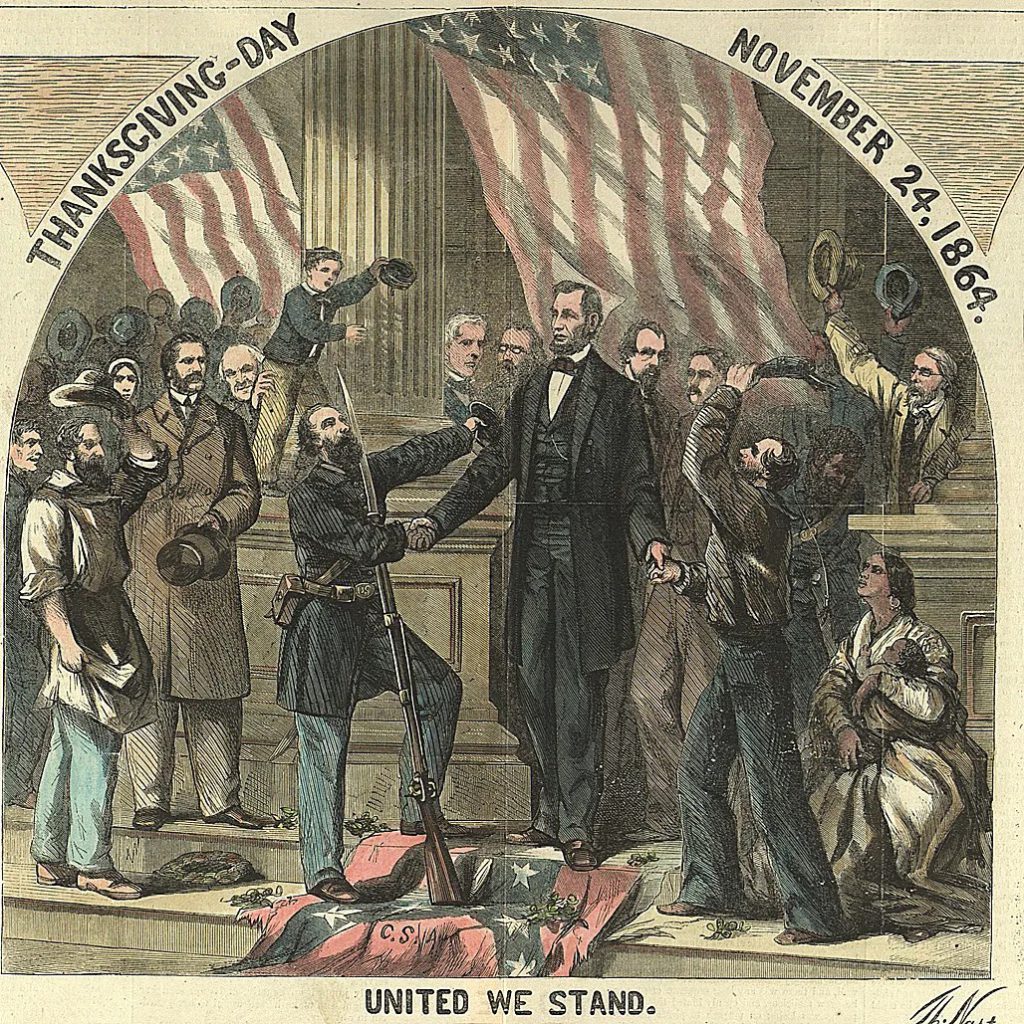

Thanksgiving: A Civil War Call For Unity

As Americans prepare each year for a festive Thanksgiving dinner, it’s worth remembering how deeply the holiday’s modern identity was shaped by the Civil War — and by the long efforts of a single woman who lobbied tirelessly for a national day of thanks. The story of what soldiers ate in camps, and what the holiday came to symbolize, shows that Thanksgiving as we know it was born in hardship, hope, and national war.

From Regional Rites to a National Holiday — Enter Sarah Josepha Hale

Before the 1860s, Thanksgiving existed in many places (especially New England) — but there was no consistent national day of observance. That began to change thanks largely to Sarah Josepha Hale. Known today as the “Mother of Thanksgiving,” Hale was a prominent writer and editor (of “Godey’s Lady’s Book”), a wildly influential 19th-century magazine for women. If you haven’t heard of “Godey’s Lady’s Book” you have likely heard her short rhyme “Mary Had a Little Lamb” at one time or another. Yes, THAT “Mary Had a Little Lamb”

Beginning in the 1840s, Hale used the pages of Godey’s to argue for a national Thanksgiving holiday. She published not only essays and editorials, but poems, family stories, and even recipes — roast turkey, pumpkin pie, and other autumnal fare — to build a vision of what Thanksgiving could look like across the entire nation.

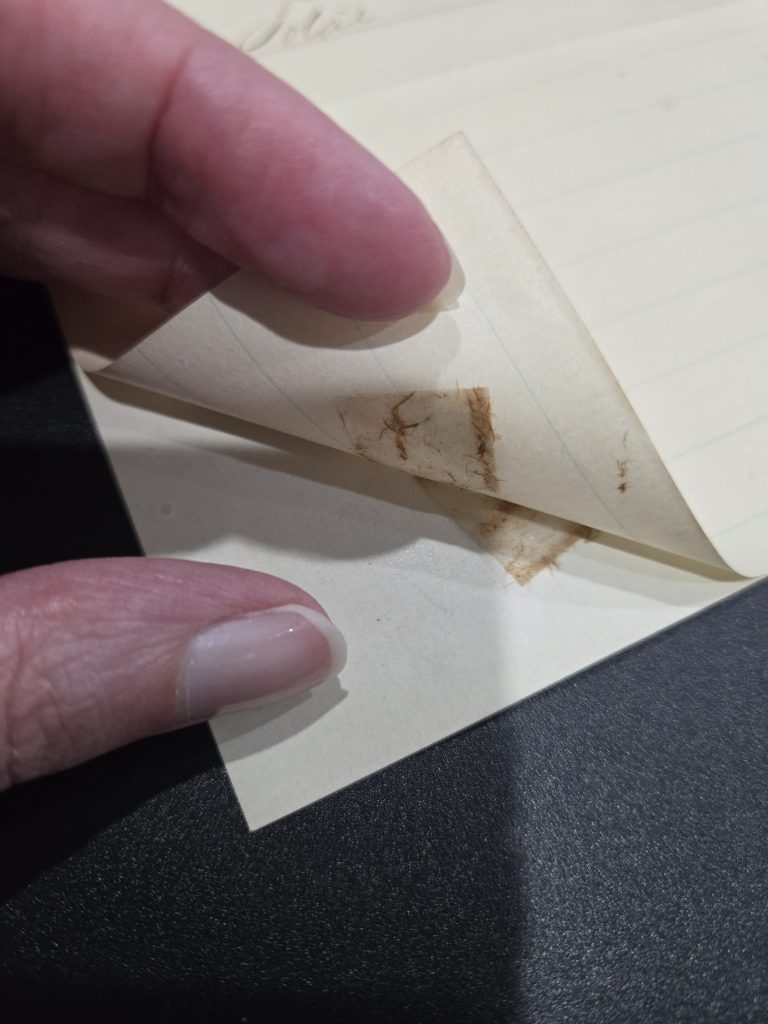

In her own words (in a letter to Lincoln dated September 28, 1863), she urged him to make Thanksgiving “a National and fixed Union Festival.” She wrote that there had been, “for some years past, an increasing interest felt in our land to have the Thanksgiving held on the same day, in all the States,” and that only a national proclamation could “secure forever the permanency and unity of our great American Festival of Thanksgiving.”

After decades of lobbying presidents (Zachary Taylor, Millard Fillmore, Franklin Pierce, James Buchanan), Hale’s persistence finally paid off — but only in the midst of a bloody civil war. Thus, by the time Lincoln issued his famous 1863 Thanksgiving proclamation, the idea had been primed for decades — and the timing of the Civil War made it more urgent.

The 1863 Proclamation — A Nation at War Still Asked to Give Thanks

On October 3, 1863, Lincoln issued what is now considered the first “modern” national Thanksgiving proclamation. He named the last Thursday of November “a day of Thanksgiving and Praise” for the whole country.

In that proclamation, Lincoln did not ignore the reality of war. He acknowledged that the United States was in “a civil war of unequalled magnitude and severity.” Yet he urged citizens — “fellow-citizens in every part of the United States, and also those who are at sea and those sojourning in foreign lands” — to unite in gratitude for the “blessings of fruitful fields and healthful skies,” for the nation’s continuance despite trials, and for the promise of peace and restoration.

Hale’s dream of a “permanent” day of thanksgiving had become reality — at a time when unity was more fragile and more necessary than ever.

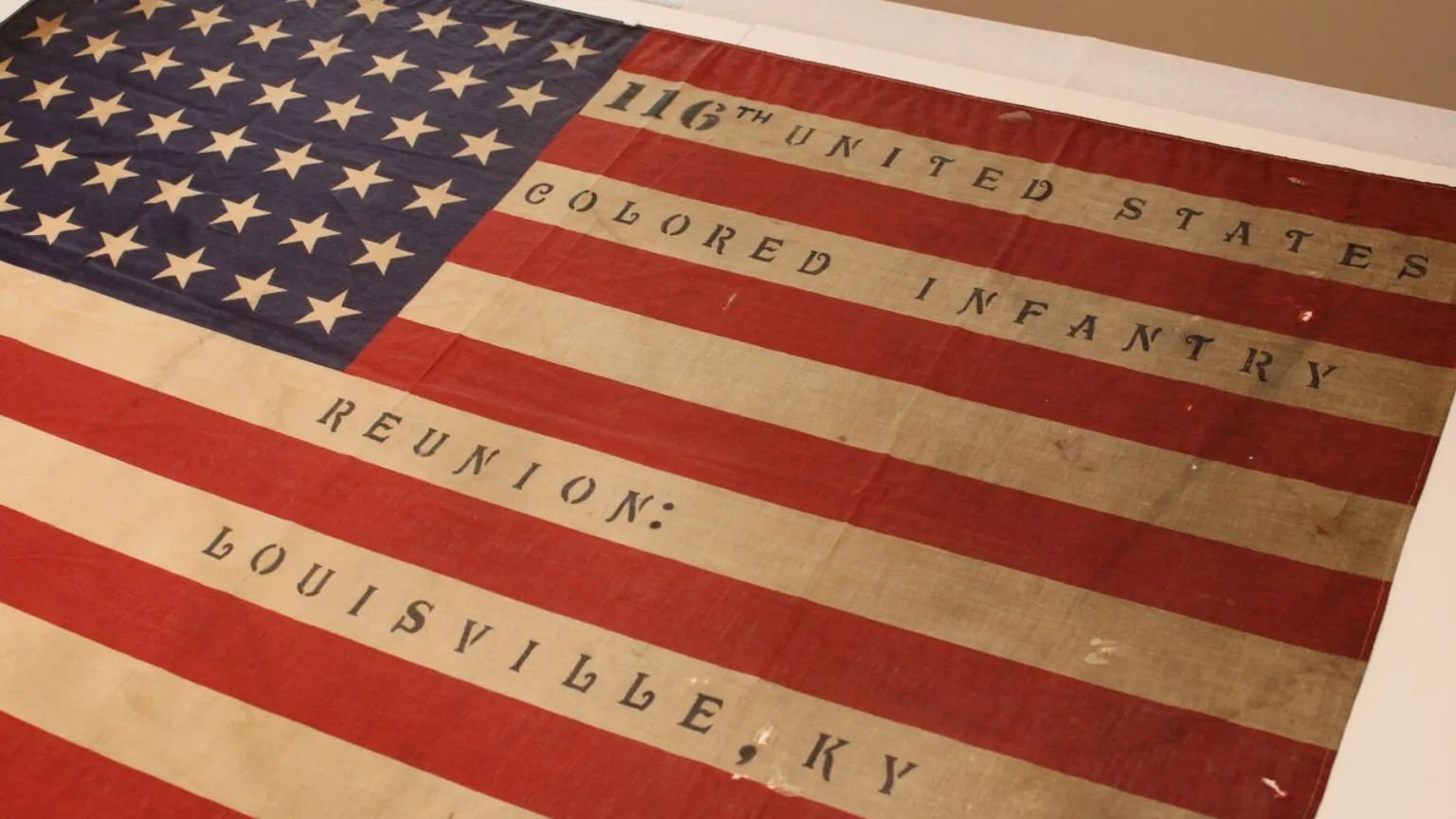

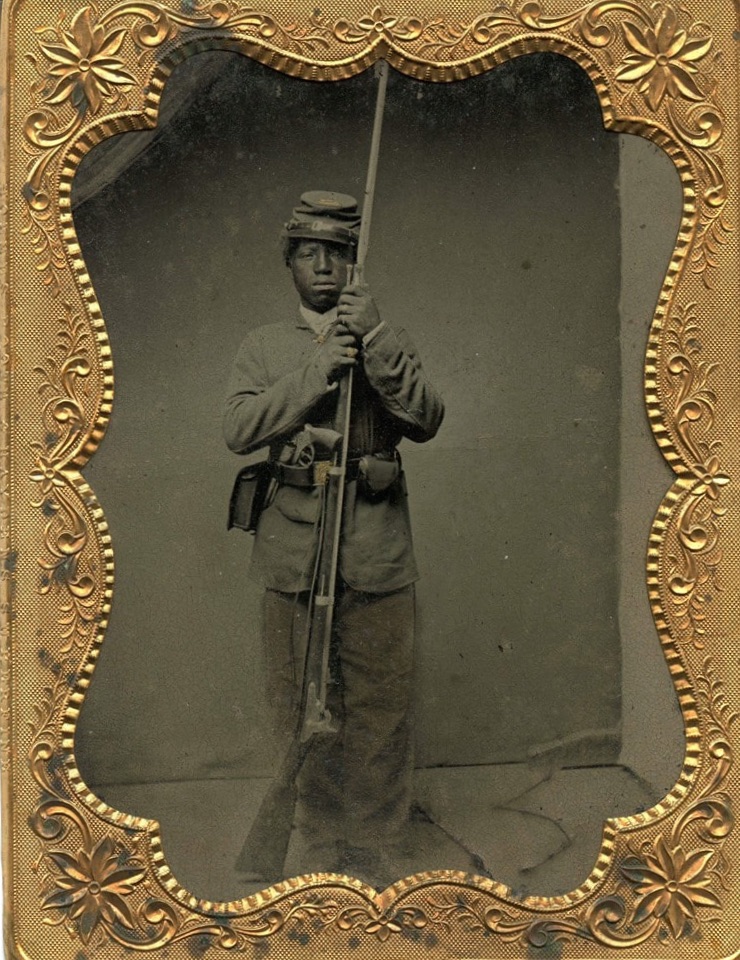

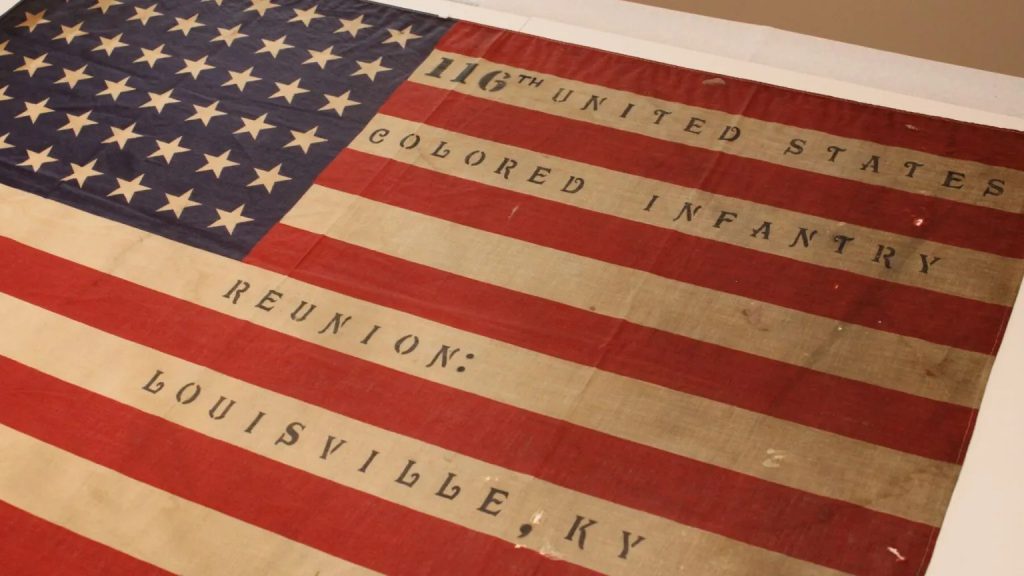

Thanksgiving on the Front Lines: Soldier Celebrations During the Civil War

But what did Thanksgiving look like for the soldiers who were living through those years of unimaginable hardship? The reality was mixed — often modest, sometimes surprisingly festive. According to a recent article in Staunton Star‑Times, many men serving in the war made do with whatever they had:

In a letter home after Thanksgiving 1861, an Illinois infantryman described his holiday meal bluntly: “hard bread” and salt pork. He added wistfully that during the day he thought of “you at home having your nice dinners,” and that he wished “maybe that you might present a plate to some of us soldiers filled with your own goodies.”

Private Zebina Bickford of the 6th Vermont Infantry, writing from camp in Virginia, joked to his family that though they got a care package — “a box of clothing and a few nicknacks consisting of eatables” — the supper might as well have been “a piece of sour bread and salt pork.” Still, he added with gratitude that “some of mother’s cookies and doughnuts” made the evening “very good Thanksgiving for us.” It would tragically be his last Thanksgiving — he died the following April.

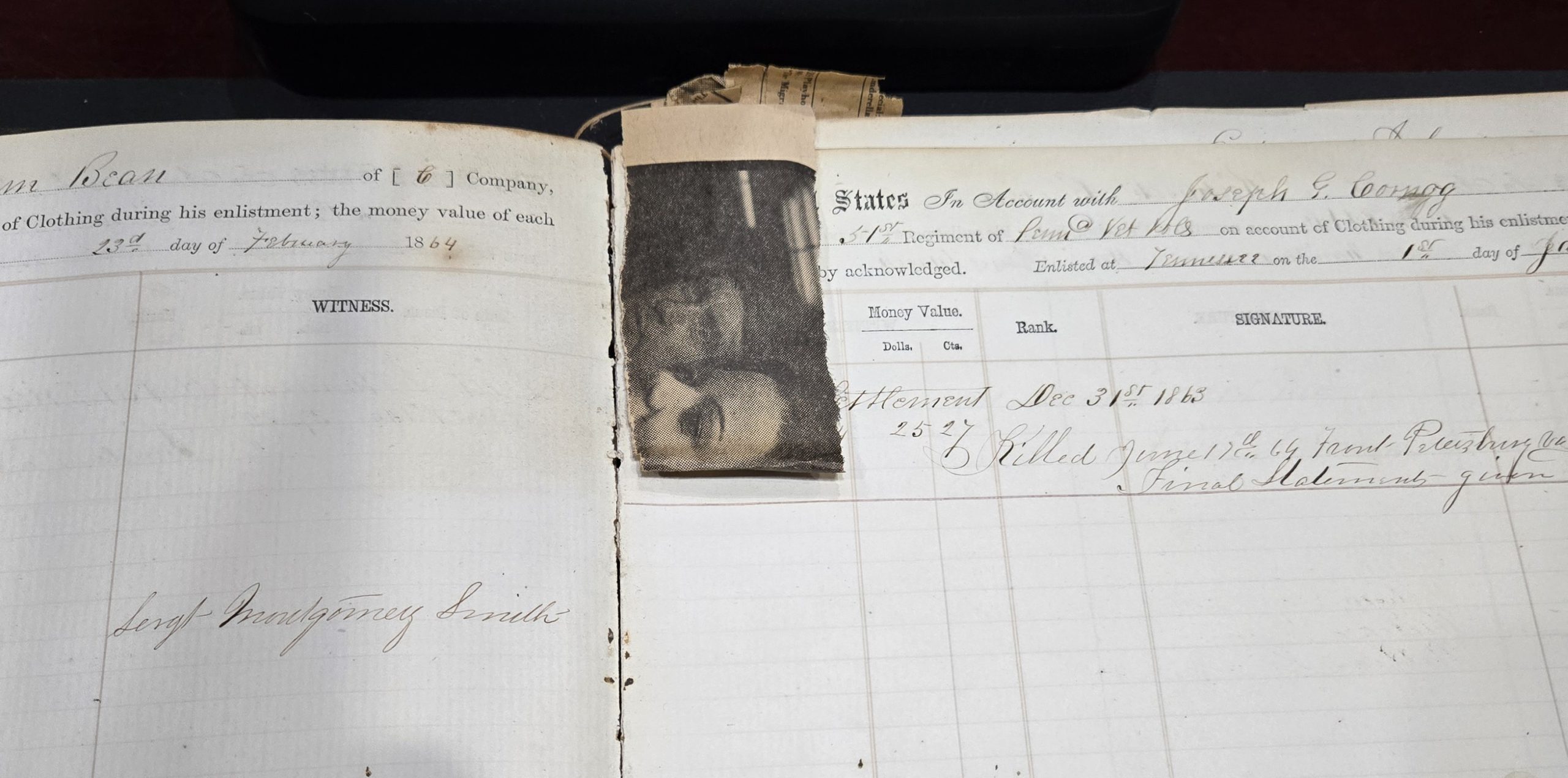

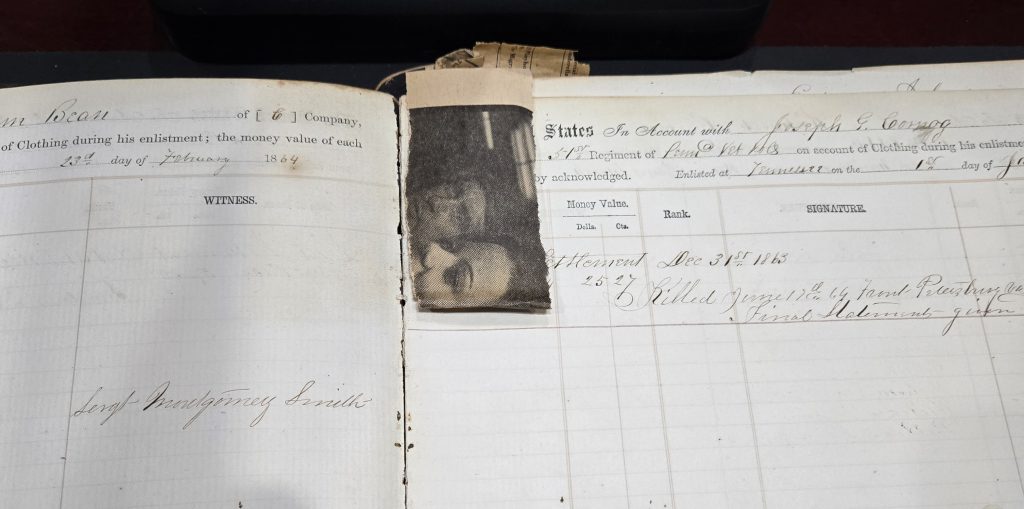

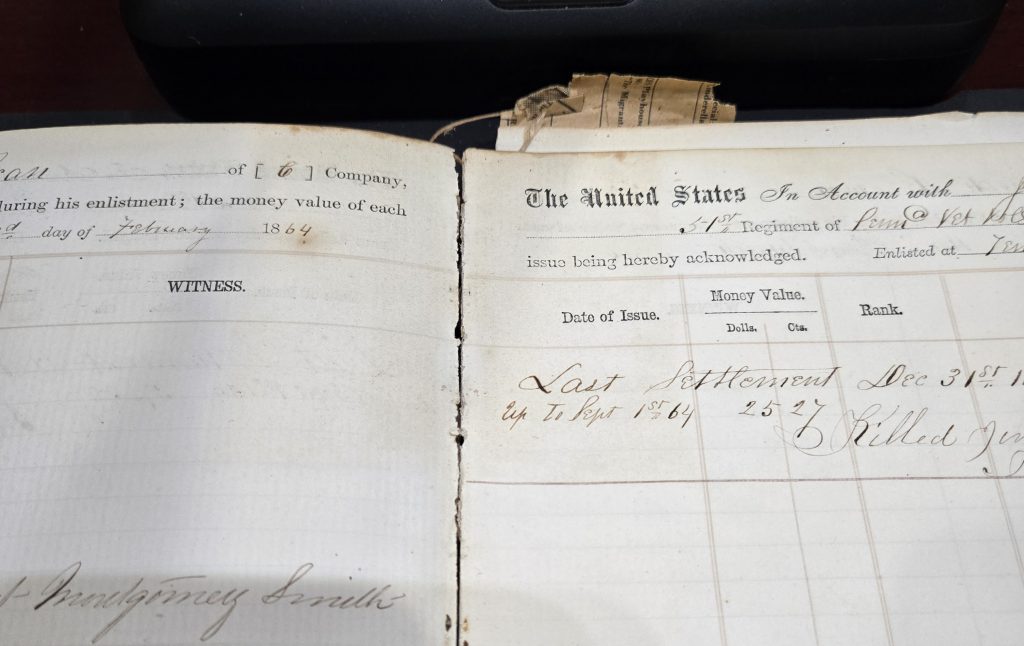

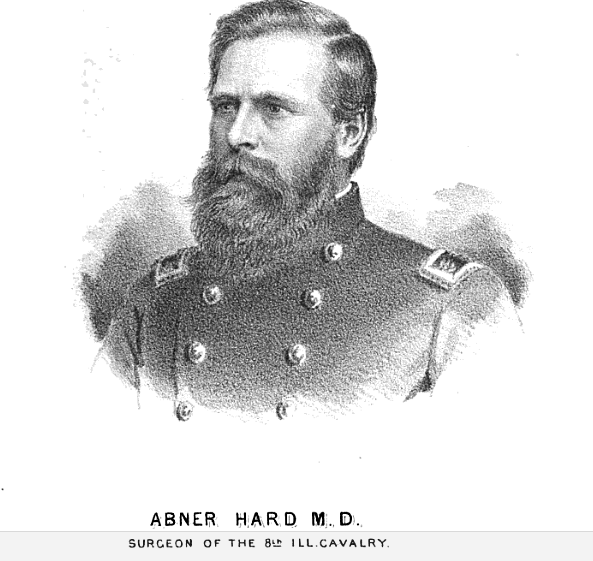

On the other hand, not all celebrations were austere. A doctor in the 114th Ohio regiment, Asa Bean, described a November 27, 1862 “surprise party” for soldiers and nurses. The feast, by wartime standards, was rich: “roast turkey, chicken, pigeon and oysters stewed,” along with “baked chicken, boiled potatoes, turnips, apple butter and cheese butter.”

Elsewhere — at a fort in Georgia — Federal soldiers held a full “fete and festival,” with target practice, foot races, a rowing match, a greased-pole contest, even a greased-pig race, and a “burlesque dress parade.”

Some soldiers used Thanksgiving not for feasting, but for spiritual reflection and a brief escape from military discipline. On the first official nationwide Thanksgiving in 1863, a soldier in the 95th Illinois, Sewell Van Alstine, noted in his diary that he “went to town” and “heard an excellent discourse by an army chaplain at the Presbyterian Church.” He also recorded that there was “no drill today,” a welcome — however brief — respite.

In the midst of war, Thanksgiving could mean anything from a meager meal of hardtack to a modest but morale-boosting feast, or simply a moment of rest and spiritual comfort. As one soldier wrote, reflecting on donated food and treats: “it isn’t the turkey, but the idea that we care for” that mattered.

Why Lincoln’s Proclamation — and Hale’s Work — Resonated So Deeply

Given the grim backdrop of the Civil War, why would a president ask the public to give thanks? Why would soldiers bother, when hardship and danger hovered daily?

Part of the answer lies in what Hale believed: a shared Thanksgiving — celebrated on the same date across every state — could help bind a fractured nation together. She viewed the holiday as more than mere parlor-room feasts: she argued it could become a moral and social force, a “Union Festival” to remind Americans of their shared identity, their common institutions, and their bonds of home-and-country.

Lincoln’s 1863 proclamation echoed that hope. In it, he acknowledged the suffering and the war — but also invited the American people to look beyond present suffering, toward blessings still present: abundant harvests, prosperous industry, growing population — signs of resilience and promise.

For a country ripped apart through bloody battles, loss, and political division, Thanksgiving could become a moment of solidarity — a way to quietly affirm that, even amid fratricidal war, the nation still held together.

And for the soldiers, home-front, families, and the wounded, that reminder carried weight. A simple meal — or a humble pie, or tokens from home — could mean more than words of comfort; it could stand for hope, connection, and recognition that their sacrifice was seen.

What This History Teaches Us Today

When we sit down at our Thanksgiving tables — laden with turkey, pies, stuffing, casseroles — it’s easy to forget that the modern holiday was forged in a time of violence, loss, and a desperate desire for unity.

The 1863 proclamation reminds us that Thanksgiving was turned into a national institution exactly when the nation was at war with itself. It was meant, in part, to help heal — not just individual wounds, but national ones.

The modest, improvised celebrations of Civil War soldiers remind us that thanksgiving doesn’t depend on abundance. Even “hard bread and salt pork,” plus a few cookies from home, sufficed — because gratitude, at its core, is about appreciating what remains, not what’s missing.

The decades-long advocacy of Sarah Josepha Hale shows the power of persistence and conviction: a private citizen, using words and influence, helped bring a holiday into being — something that would long outlast her lifetime.

This Thanksgiving, maybe take a moment to reflect not just on what’s on your plate — but on where the holiday comes from. On the soldiers who paused for a prayer, a letter home, a simple supper. On a woman who believed a shared day of gratitude could bind together a fractured country. On a president who — in the darkest days of war — still called for hope, unity, and thanksgiving.

Bibliography

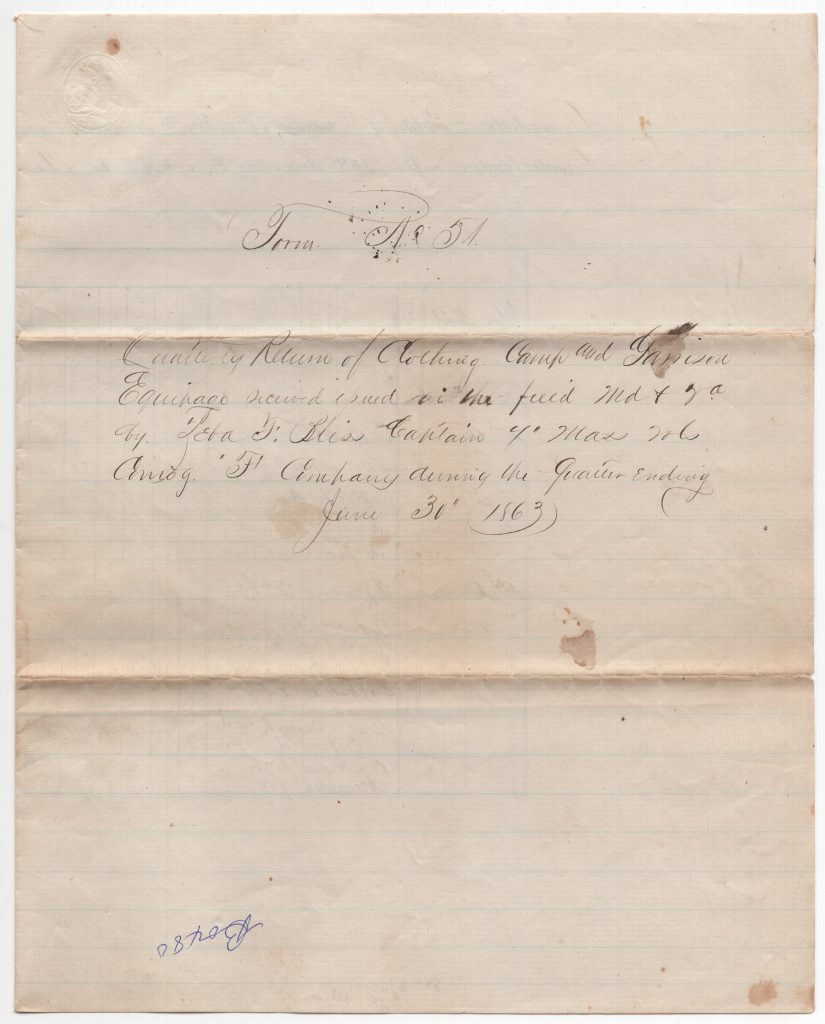

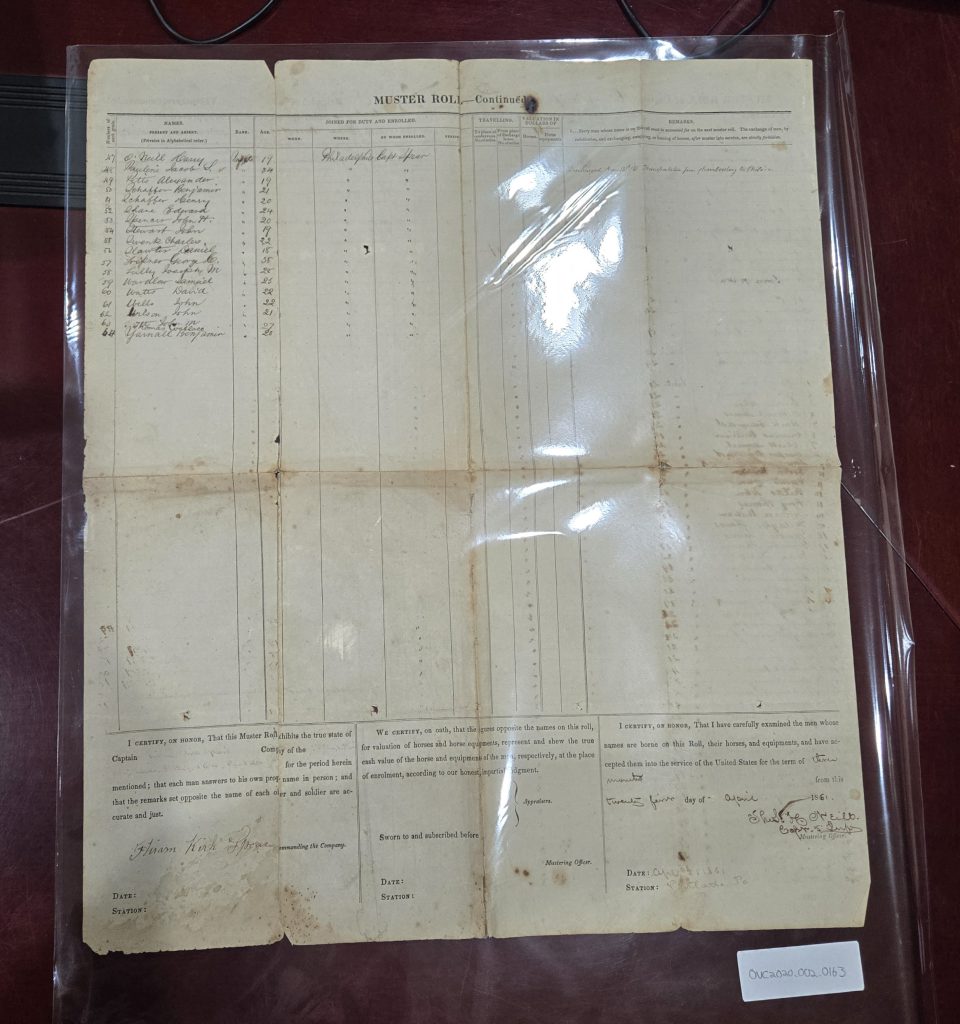

For more primary source reading on Thanksgiving, visit the Research Arsenal Civil War database and search for the keyword “Thanksgiving” in a library of your choice. There are 200 letters currently on file that have “Thanksgiving” in the transcriptions.

Battlefields.org. “Abraham Lincoln’s Proclamation of Thanksgiving.” American Battlefield Trust. Accessed 2025.

https://www.battlefields.org/learn/primary-sources/abraham-lincolns-proclamation-thanksgiving.

Staunton Star-Times. “Thanksgiving on the Front Lines: How Civil War Soldiers Celebrated the Holiday.” Staunton Star-Times, November 19, 2025.

https://www.stauntonstartimes.com/story/2025/11/19/opinion/thanksgiving-on-the-front-lines-how-civil-war-soldiers-celebrated-the-holiday/7021.html.

National Park Service (NPS). “Lincoln and Thanksgiving.” Lincoln Home National Historic Site. Accessed 2025.

https://www.nps.gov/liho/learn/historyculture/lincoln-and-thanksgiving.htm.

Hudson Institute. “Giving Thanks: Sarah Josepha Hale.” Accessed 2025.

https://www.hudson.org/domestic-policy/giving-thanks-sarah-josepha-hale.

History.com Editors. “Abraham Lincoln and the Mother of Thanksgiving.” History.com. Accessed 2025.

https://www.history.com/articles/abraham-lincoln-and-the-mother-of-thanksgiving.

WomensHistory.org. “Sarah Josepha Hale.” National Women’s History Museum. Accessed 2025.

https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/sarah-hale.

The Old Farmer’s Almanac. “Sarah Josepha Hale: The Godmother of Thanksgiving.” Accessed 2025.

https://www.almanac.com/sarah-josepha-hale-godmother-thanksgiving.

Library of Congress Blog. “The Woman Who Helped Put Thanksgiving on the Calendar.” Library of Congress, 2024.

https://blogs.loc.gov/loc/2024/11/the-woman-who-helped-put-thanksgiving-on-the-calendar/.

Grant Camp Historical Society. “Hardscrabble.” PDF. Accessed 2025.

https://www.grantcamp.org/uploads/8/2/4/6/82468692/hardscrabble1115.pdf.