Collection Preservation Tips from The National WWII Museum

Although the National WWII Museum is a bit further forward in time than Civil War collectors, the concept of preserving uniforms, firearms, photographs, and paper, is much the same. Their website is a fantastic resource for the private collector, so I thought it would be helpful to distill some of their key collection preservation tips down for Civil War collectors.

The National WWII Museum champions the principle “Do No Harm”, offering clear, practical guidance to help preserve such treasures for future generations. You’ll recognize the “Do no harm” motto as something I have repeated in previous posts—do not do anything to your collection that is not reversible! Put down those ballpoint pens! (If you know, you know…)

Seven Factors That Can Affect Your Collection

Before diving into specific techniques, here are seven factors that can affect your collection that you should be aware of:

- Light: UV-rich sunlight and fluorescent lighting can severely damage paper, textiles, photographs, and furniture. Keep sensitive items out of direct exposure.

- Temperature: Extreme or fluctuating temperatures wreak havoc on materials like rubber, wood, and metal. Avoid attics, basements, and unconditioned spaces.

- Humidity: Too much moisture fosters mold and pests; too little causes brittleness. Aim to maintain 45–55% relative humidity in stable environments.

- Pests: Insects like silverfish (paper), moths (textiles), and termites (wood) can be destructive. Regular inspections are essential.

- Human Handling: Oils, sweat, or makeup from hands—even gentle touching—can harm surfaces. Always use cotton or nylon gloves and avoid unnecessary handling.

- Chemical Reactions & Pollutants: Metals and marble can corrode when exposed to indoor airborne chemicals; avoid the use of acid-emitting materials.

- Inherent Vice: Some materials naturally degrade due to incompatible components—such as leather glued to wood. Periodic condition checks help catch early signs.

Tailored Preservation Tips by Material

Textiles

- Store in climate-controlled spaces, not attics or basements.

- Keep out of bright light and UV exposure.

- Use acid-free boxes—avoid ordinary cardboard or wooden drawers. Wood will off-gas over time and that can discolor and damage your collection.

- Store flat when possible; pad and support folds if necessary.

- Use acid-free tissue padding, properly padded hangers, or roll large textiles around acid-free tubes—never sealed plastic bags. If moisture is sealed inside a plastic bag with your textile, it can cause mold.

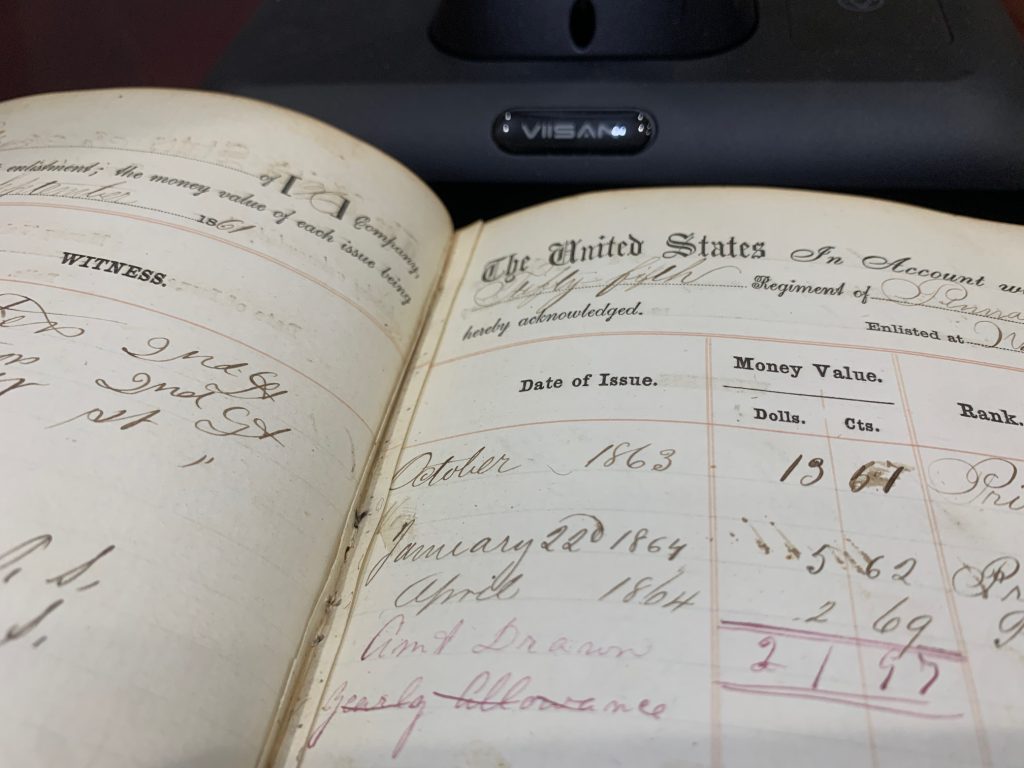

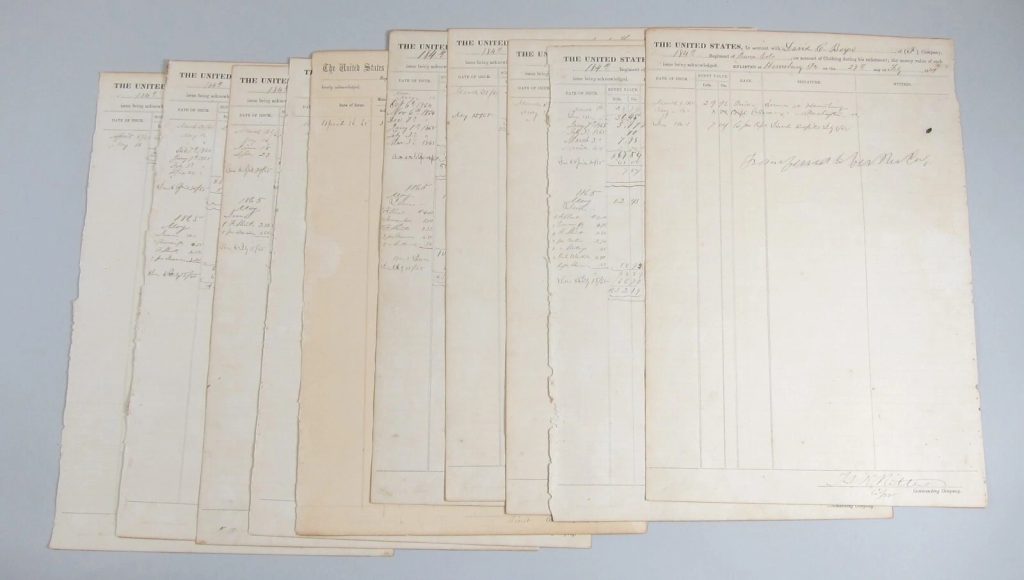

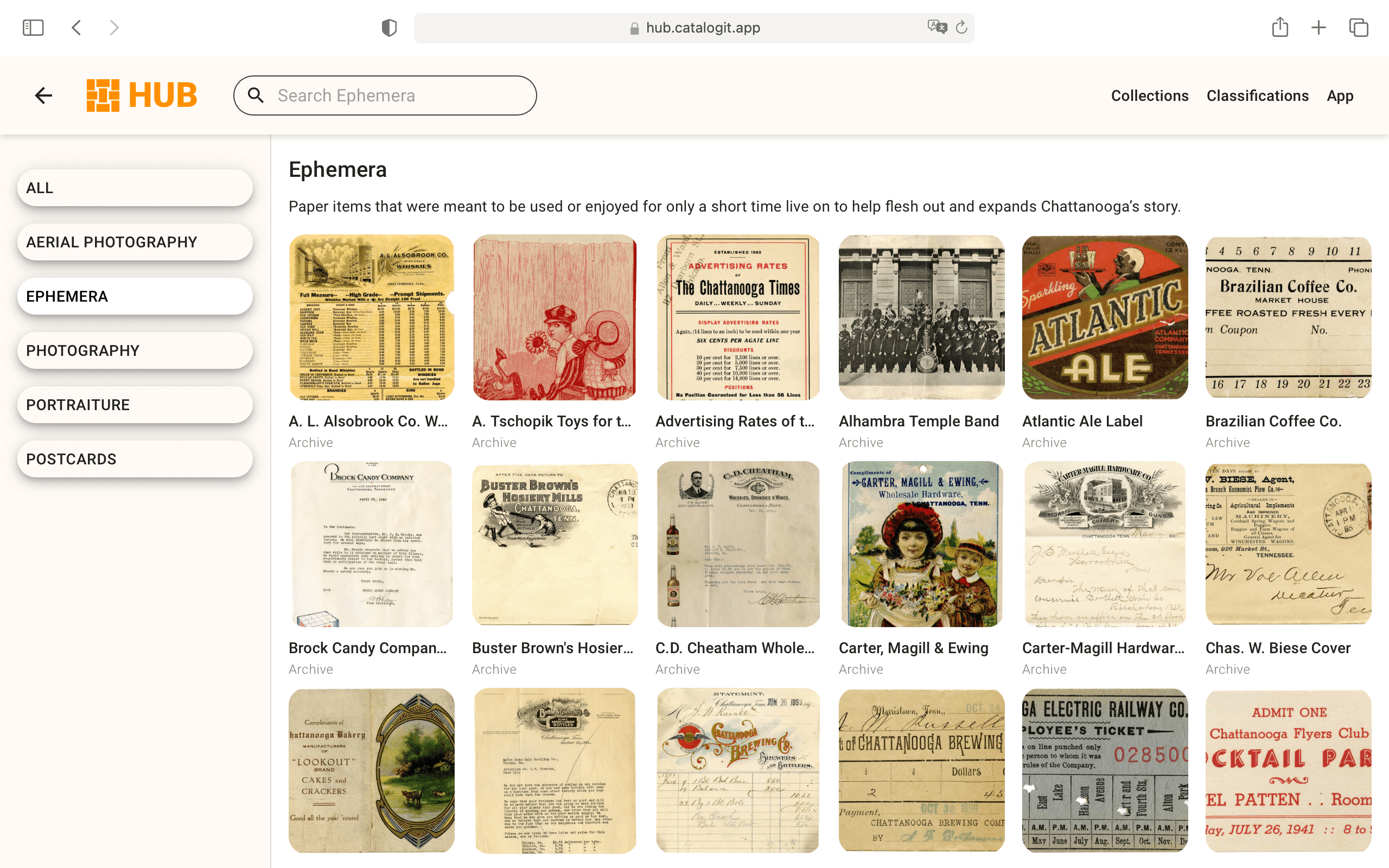

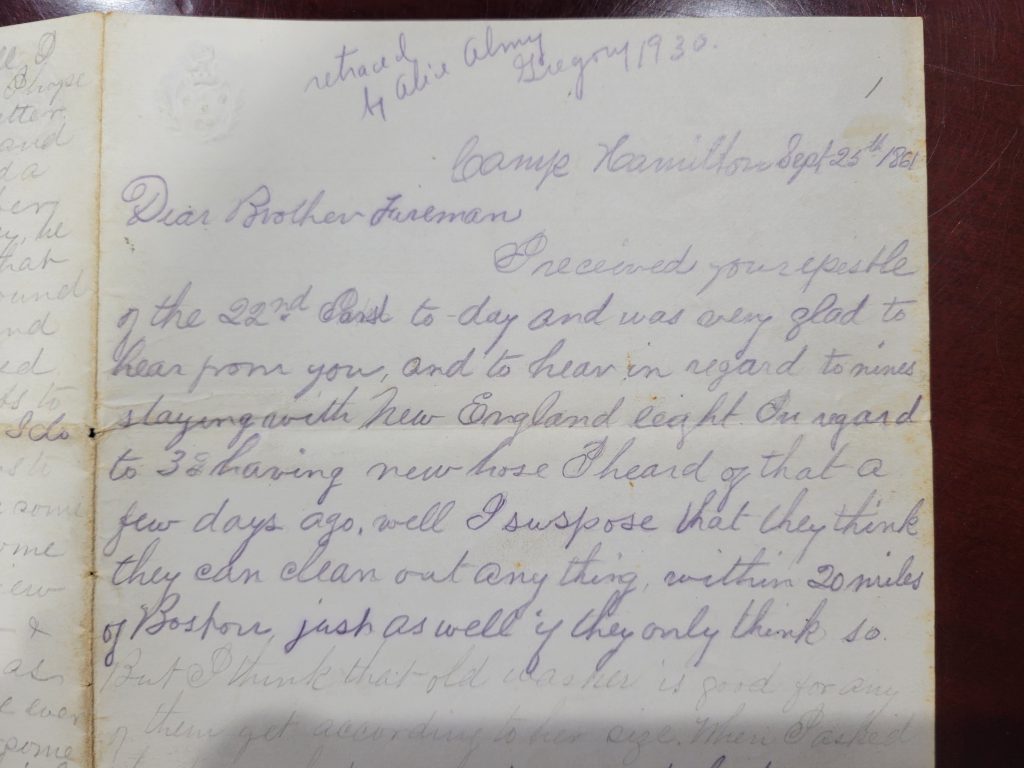

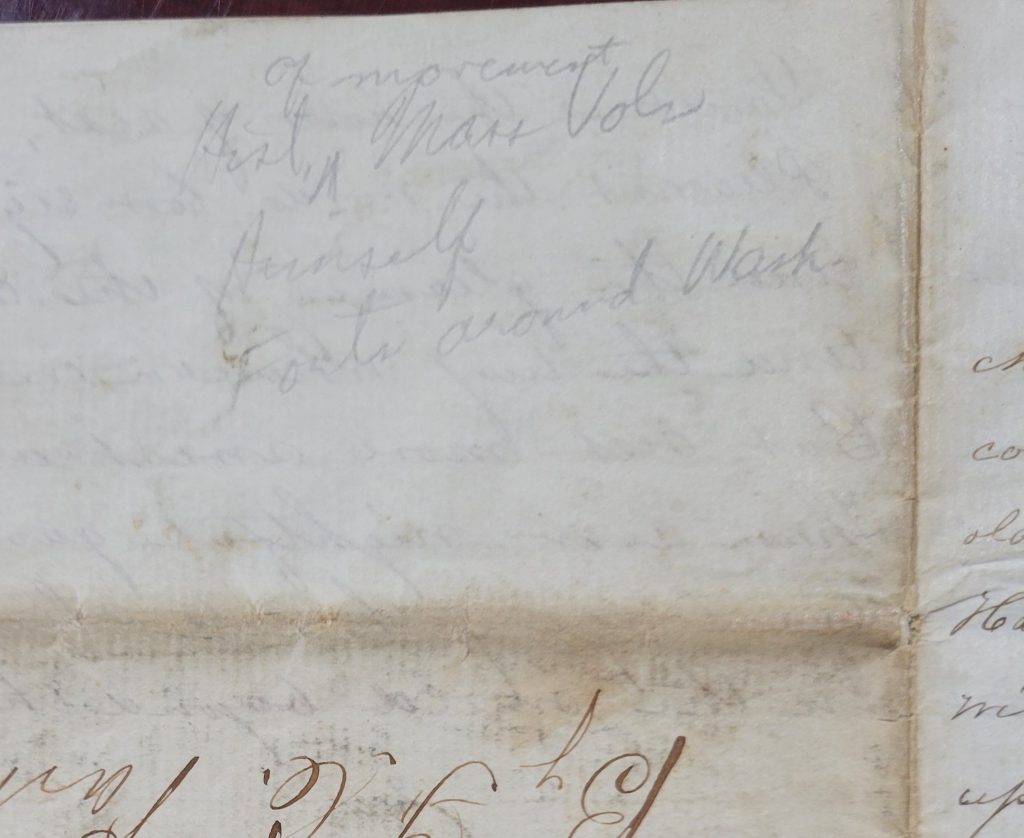

Paper

- Maintain storage below 72°F and around 50–55% humidity. This may seem like a high level of humidity, but very dry air can be as destructive as very humid air, just for different reasons. This level of humidity will keep the paper from becoming brittle and crumbling.

- Keep flat, avoid folds, and use acid-free folders/boxes/sleeves.

- Frame with archival-quality, acid-free materials and UV protective glass.

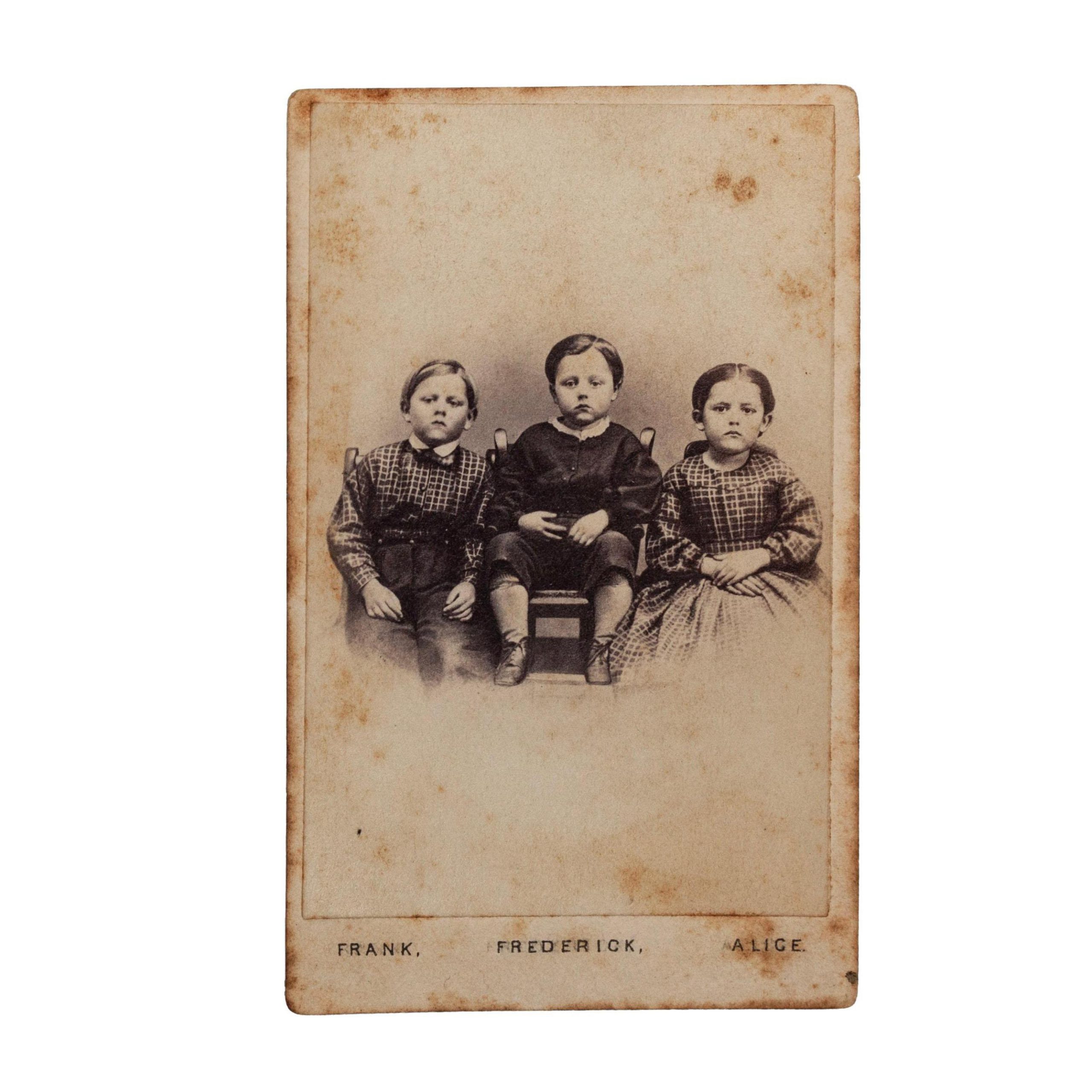

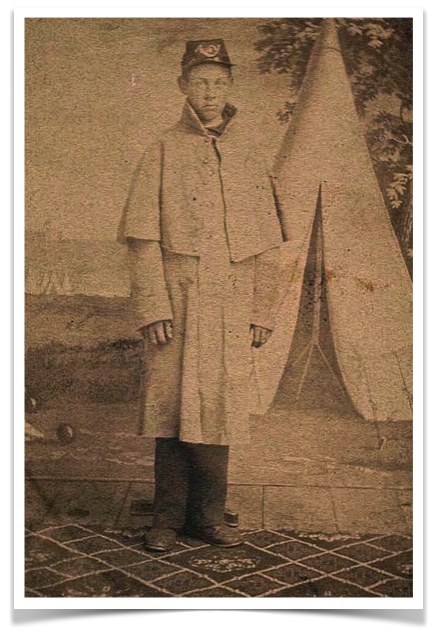

Photographs

- Store in a cool, dry place, use acid-free or inert framing materials.

- Handle by the edges, ideally with gloves—avoid touching surfaces.

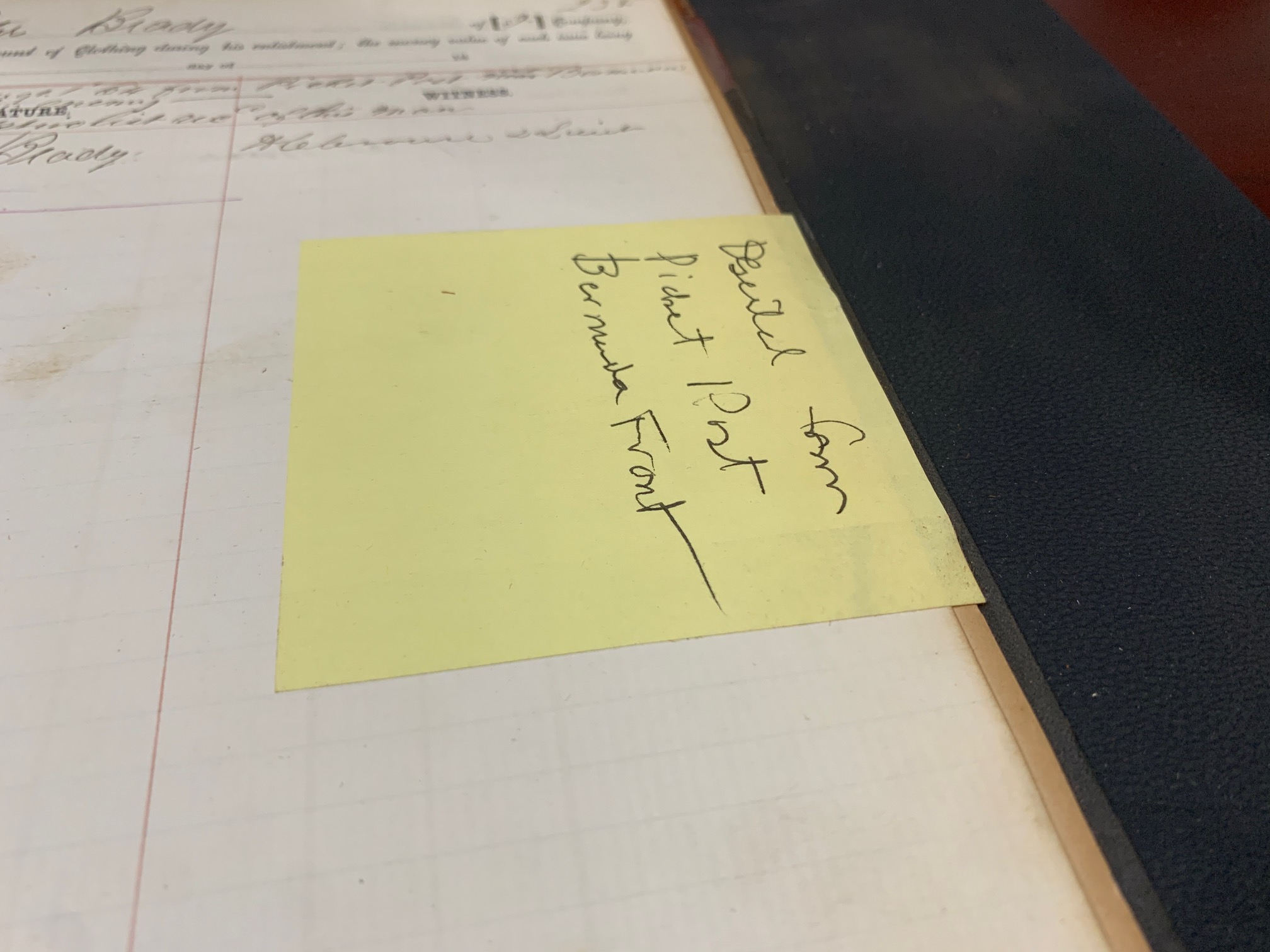

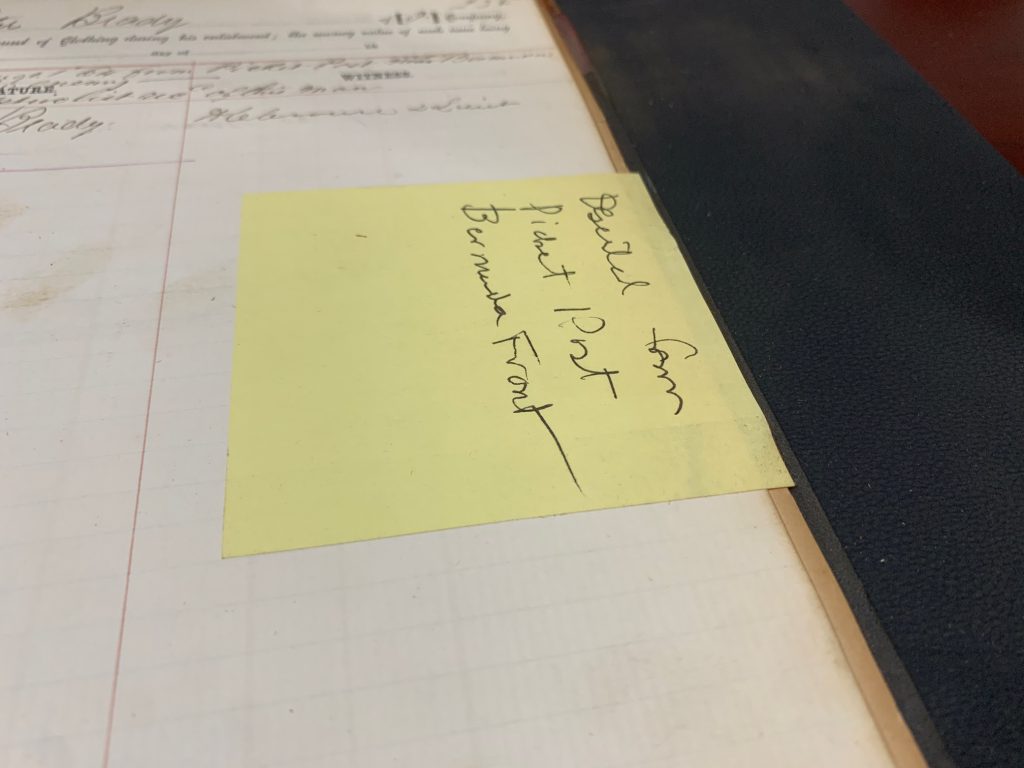

- No tape, markers, paper clips, or sticky notes; use pencil on copies or backs.

- Avoid self-adhesive photo albums at all costs. I know those were very popular in the 1980s and 1990s, but they are bad news for the longevity of your collection! Opt for acid-free sleeves or place them with archival photo corners in archival photo albums.

- Be sure to rotate any original images when displayed, or better yet, consider displaying copies, leaving originals safely stored.

Metal Artifacts

- Most metals (except gold) are prone to corrosion—store in dry, conditioned spaces.

- Don’t polish or clean without professional consultation. Cleaning and polishing old metal ruins the aged patina on the item, which can also be an issue when determining authenticity of a piece.

- Always wear gloves when handling. Oil from your fingers will damage the original polish on a sword or other fine steel.

- Light oil (e.g., 3-in-One) or wax (e.g., paste wax) may help preserve steel or iron—but consult a specialist for weapons.

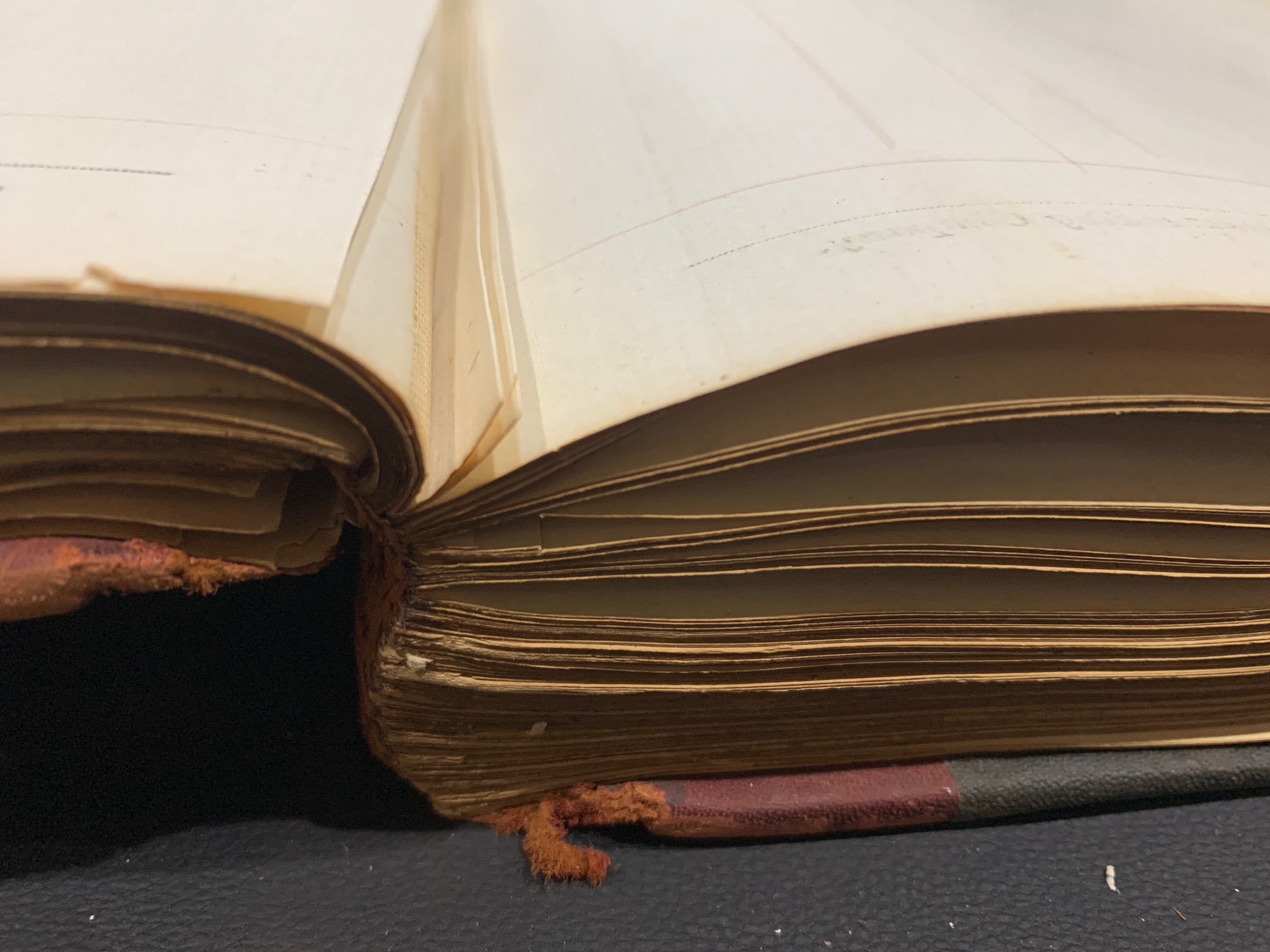

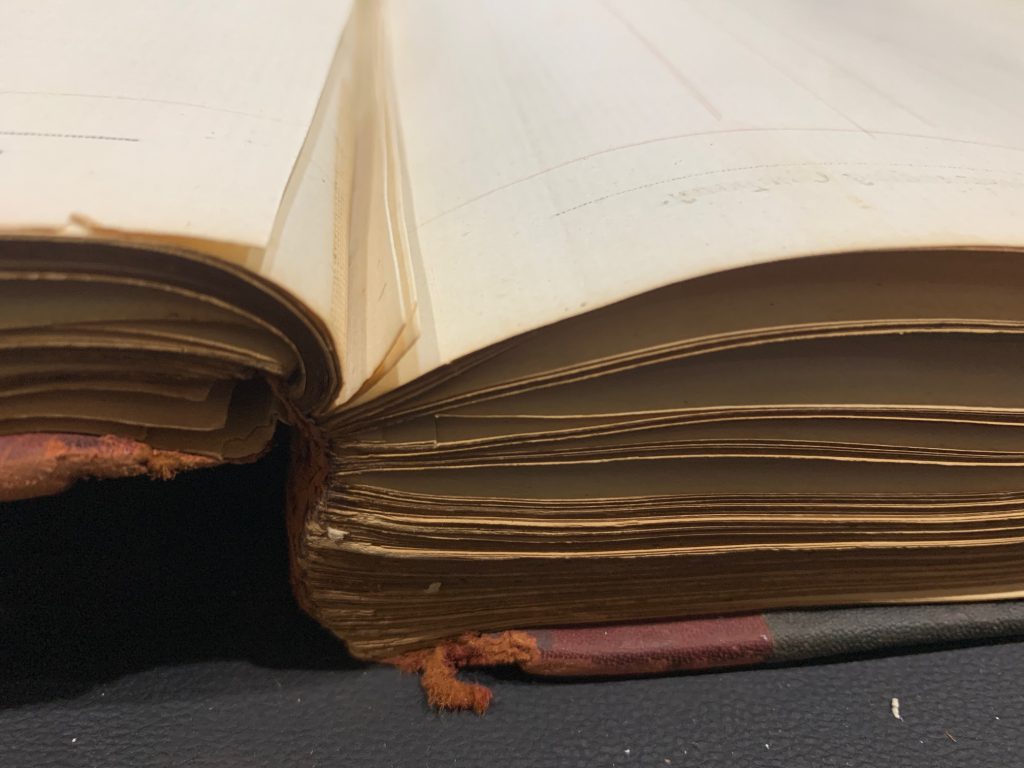

Leather

- Store in moderate humidity and temperature, away from direct light.

- If dirty, gently clean with damp cotton cloths. Please avoid saddle soap or conditioners as they can discolor and damage historic leather.

- Never apply petroleum products; they can cause irreversible damage.

- Use acid-free stuffing to maintain form—support shoes, boots, cases thoughtfully. If you have an old saddle, for example, make sure that it is fully supported on a saddle stand. If it’s sitting on a shelf, that puts the weight on parts of the saddle that are not designed to carry it, causing damage. That can also cause excessive strain on stirrups and other components. The dryer and more brittle the leather, the more of a concern this is as leather tends to stiffen over time.

- Suede and kid leather are different, and should be treated by a specialist.

Wood

- Wood objects are fairly stable if kept in consistent, moderate environments.

- Avoid direct sunlight, over-cleaning, or using linseed/oil-based products.

- Wax like SC Johnson Paste Wax may offer a protective layer; oil sparingly, especially around handles or grips.

- When oiling your firearms, make sure not to get that oil onto the grips or stocks.

Expert Resources & Support

If you require a professional opinion, or are just looking for more information, these are some great resources:

- American Institute for Conservation — to find recognized conservators.

- Library of Congress — guidance on paper and photo care.

- Northeast Document Conservation Center — specializes in paper/photo conservation.

To purchase archival materials like acid-free boxes or folders, recommended vendors include Gaylord, Archival Methods, University Products, and Talas.