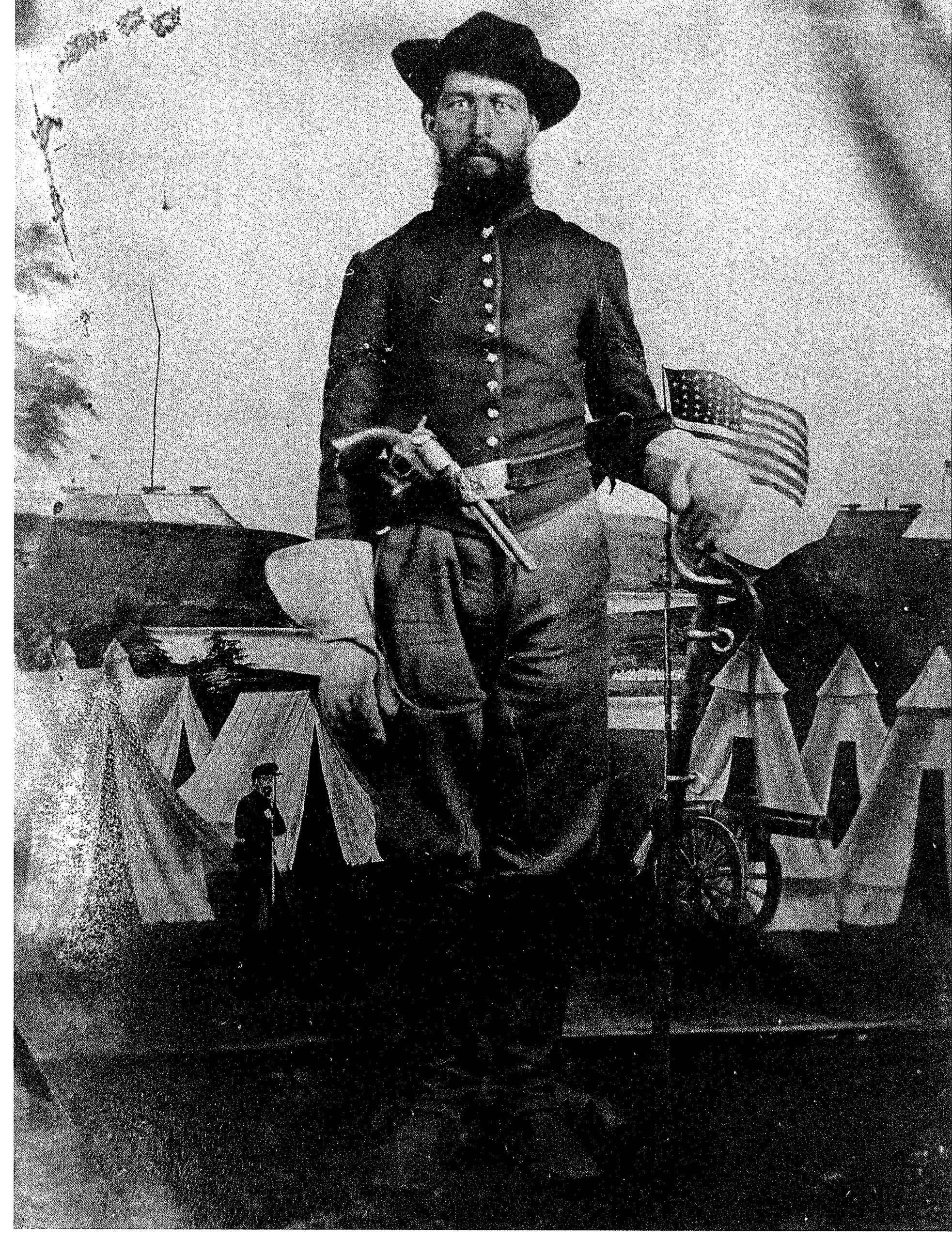

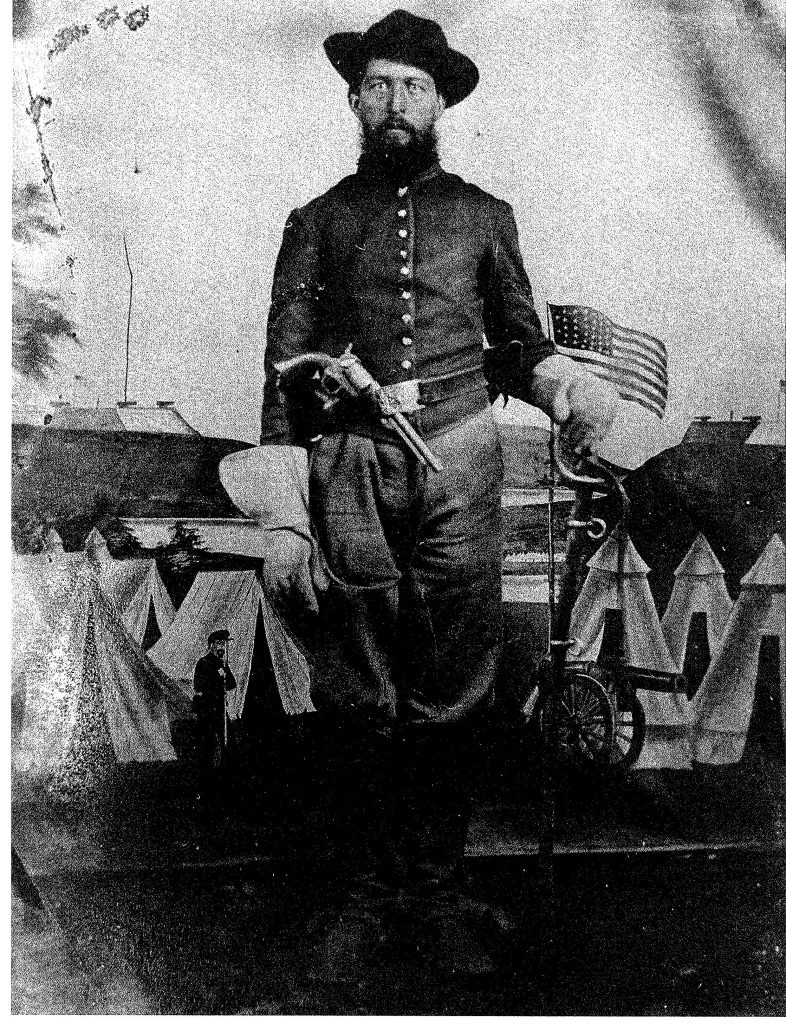

Frederick William Charles Heldman, (who was carried on rosters as Charles Heldman but signed his letters William Heldman) was an immigrant from Germany who served in Company A of the 17th Missouri Infantry. William Heldman was born in 1840 to Anton Karl Heldmann and Bertha (Falkmann) Heldmann. The family came to the United States in the 1840s. In 1851 William Heldman’s father died and his mother later remarried Eberhard Fuhr.

The 17th Missouri Infantry was also called the “Western Turner Rifles” and was made up of Union supporting German immigrants. William Heldman enlisted in the 17th Missouri Infantry in August, 1861. Previous to that he had served in the 3rd Missouri Infantry, a 90 day regiment formed in April, 1861.

William Heldman and the 3rd Missouri Infantry

The 17th Missouri Infantry was formed largely from officers and men that served in the First through Fourth Missouri Infantry regiments. William Heldman’s letters home begin during his time in the 3rd Missouri Infantry. In a letter written on August 13, 1861, William Heldman talked about his experience at the Battle of Carthage fought on July 5, 1861, and most of his company being taken prisoner.

“Sigel found Jackson on a large prairie where he found him with about 5,000 men but they were not very good armed. Sigel attacked one or two o’clock in the evening. We heard the cannons at Neosho and at three o’clock there came a man from Sigel and brought the orders for us to go back and we were all ready to go [when] there came about 1,500 secessionists from Arkansas and Texas commanded by General McCulloch.

We were all in the Court House where we had our place to stay. As soon as we seen them come, we knocked [out] all the windows and shut the doors, [and] got ready to shoot through the windows. The secessionists stopped and two men came up to the fence with a white handkerchief and asked our Captain to surrender and our Captain came in to us and told us. We told him we would sooner die. Our Captain told us we could not fight against so many and our Captain asked them if they would treat us just [if] we would surrender to them and they promised by their honor and so we give up. They kept us three days and then we had 85 miles to go without anything to eat. We got back to St. Louis and we have been here a good while waiting for our money and our discharge but I think we will soon get it.”

Soon after his return to St. Louis, William Heldman, along with many men of his regiment, joined the 17th Missouri Infantry.

Fighting in Missouri and Arkansas

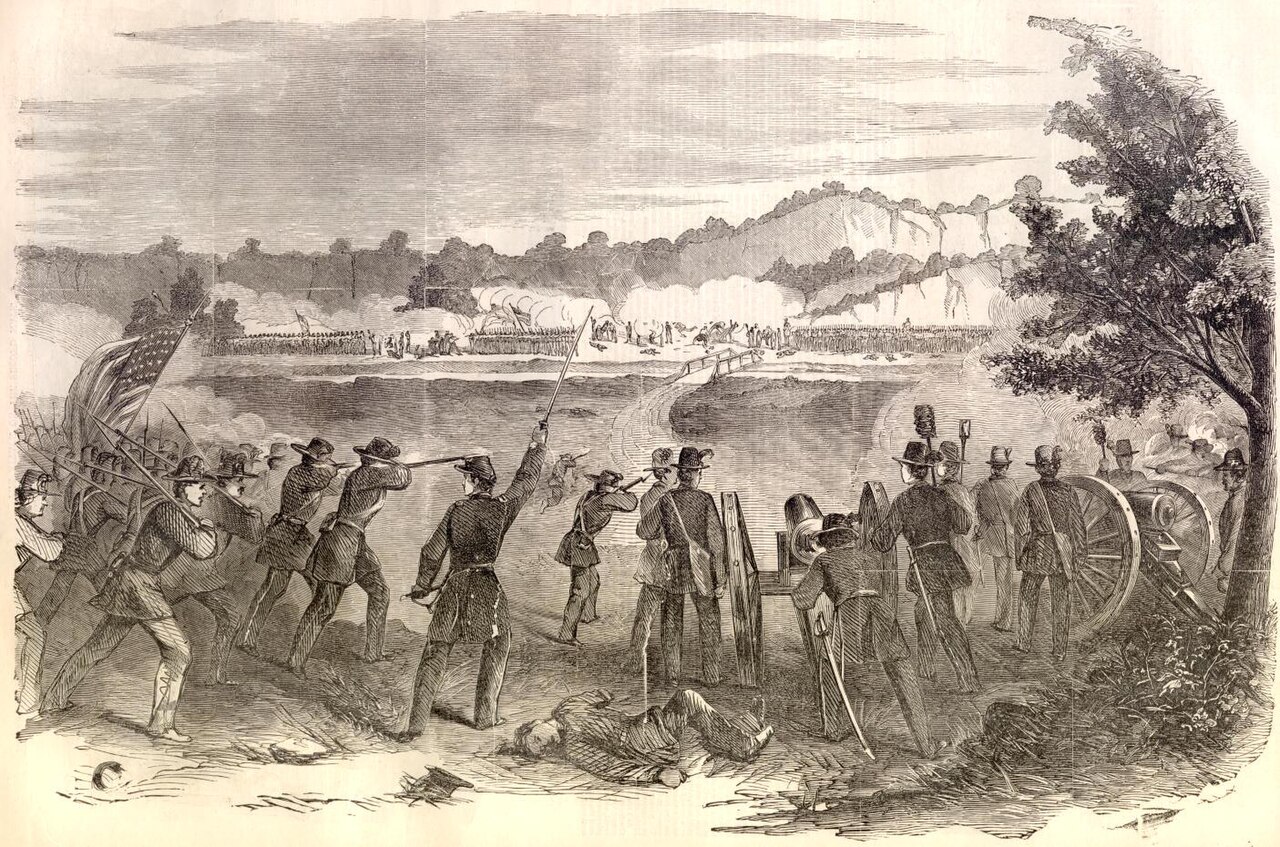

The 17th Missouri Infantry fought throughout Missouri and Arkansas in fall of 1861 through summer 1862. On October 5, 1861, William wrote about some recent skirmishing near Sedalia, Missouri.

“We have left St. Louis and we are in a little town called Sedalia. We have to wait for a battle every day. Yesterday our pickets had a fight. We lost one man. How many the enemy lost, we do not know but we are not afraid now for we have a good many soldiers up here now. The enemy entirely surrendered. The only got one way about 40 miles to get out. We took three prisoners last night and they had hardly any clothes on and they said that the whole army was the same way.”

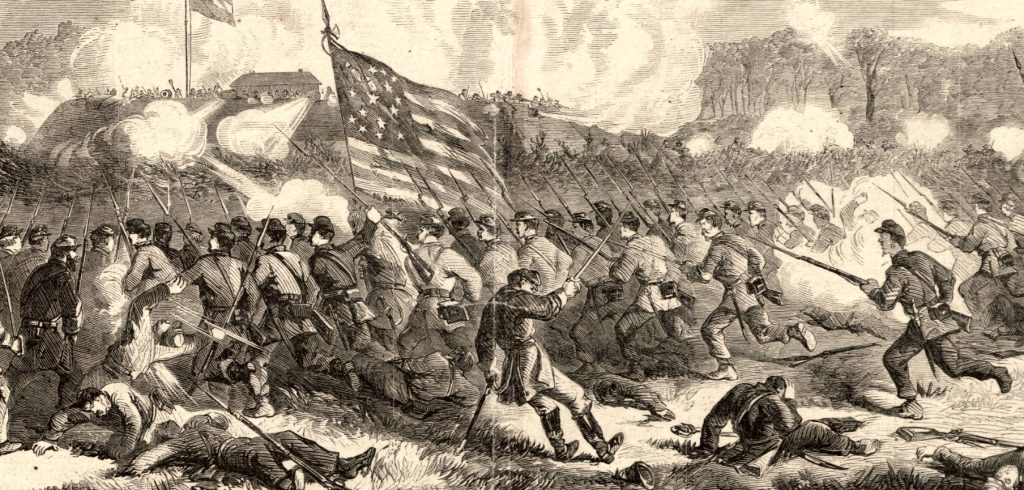

On March 1, 1862, William was writing from Osage, Arkansas when he detailed the 17th Missouri Infantry’s pursuit of the Confederate forces under the command of General Sterling Price.

“At two o’clock we started in pursuit of Price. We had a hard time then. We had to march very hard. We marched ten miles without stopping and without cooking, but we could not catch Price. General [Jefferson C.] Davis took another road and got to chase Price’s rear guard and he fired two cannon shells at the men and killed 7 men and wounded many and they galloped away.

The next day we marched too Cassville. About 10 miles behind Cassville, our cavalry had a fight. They took 60 prisoners and killed a good many. Our cavalry was always close behind Price and our flying batteries troubled him a great deal. We has 12 from our cavalry called flying batteries. We marched from Cassville and marched to the Arkansas line. Near the line is very high mountains and the valley is so small—just wide enough for the road.

The next day we had a fight at [Little] Sugar Creek and that was the last was seen of him. We lost 15 men killed and 5 wounded.”

The fighting in Arkansas was quite gruesome, and William Heldman detailed the horrific treatment of a captured Union soldier by guerillas in a letter dated July 18, 1862.

“You have not heard of us for a long time for we have been traveling around in the wilderness of Arkansas. We had to fight with miserable robber [guerrilla] bands most every day. General Steele’s troops had a fight with them. They killed 130 of them. How many they wounded I do not know for they took them all along. Our men lost 17 killed and 42 wounded. The secesh took one of our men prisoner and they took him and tied his arms behind him around a tree and then they cut his arms off in the shoulder and give him 7 shots in the lower part of his body. Who would save the life of any such a miserable being?”

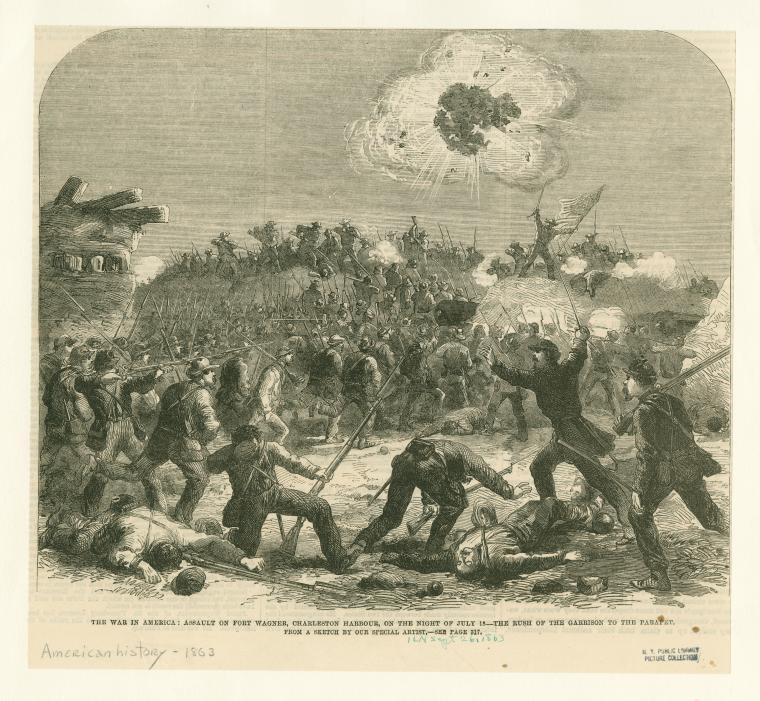

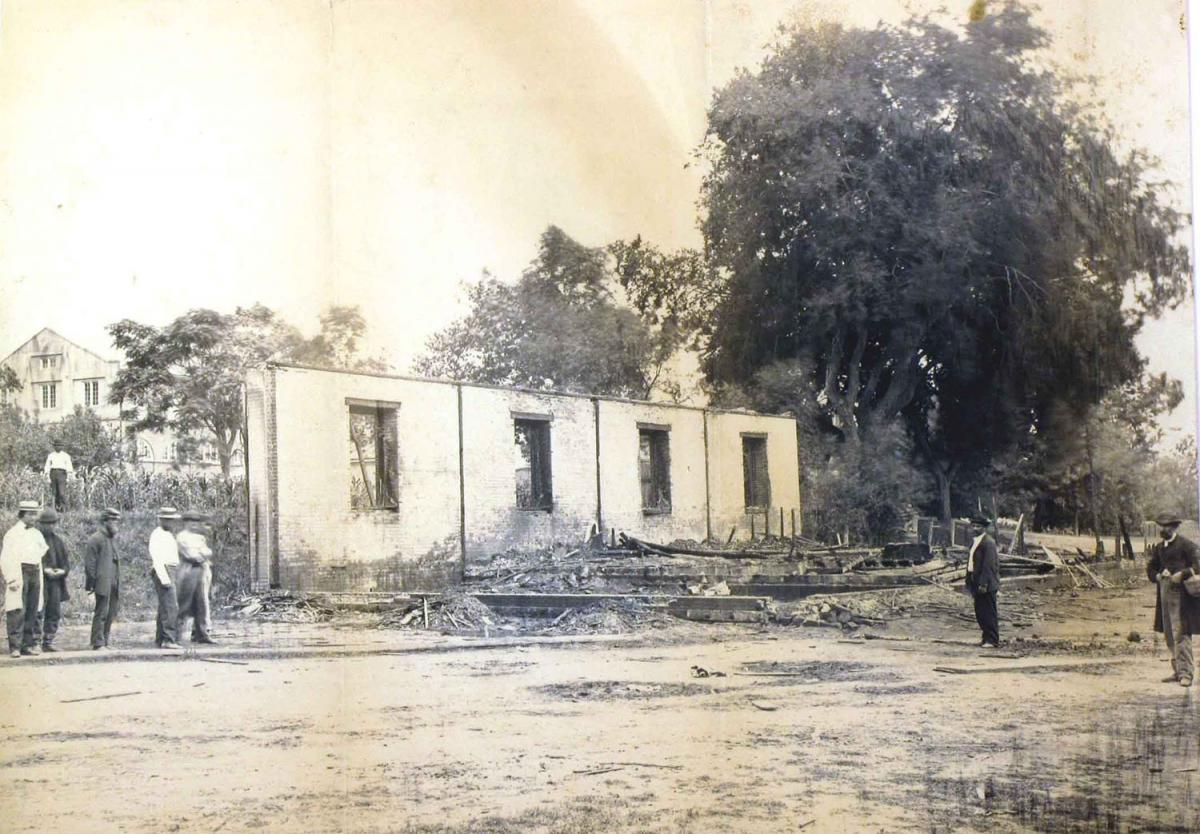

The 17th Missouri Infantry at Vicksburg

William Heldmen’s brother, Theodore, enlisted in the 17th Missouri Infantry in the fall of 1862. Unfortunately, he was soon taken ill and discharged for disability. In January, 1863, the 17th Missouri Infantry began fighting around Vicksburg. On January 15, 1863, William Heldman wrote to his brother about the recent battles.

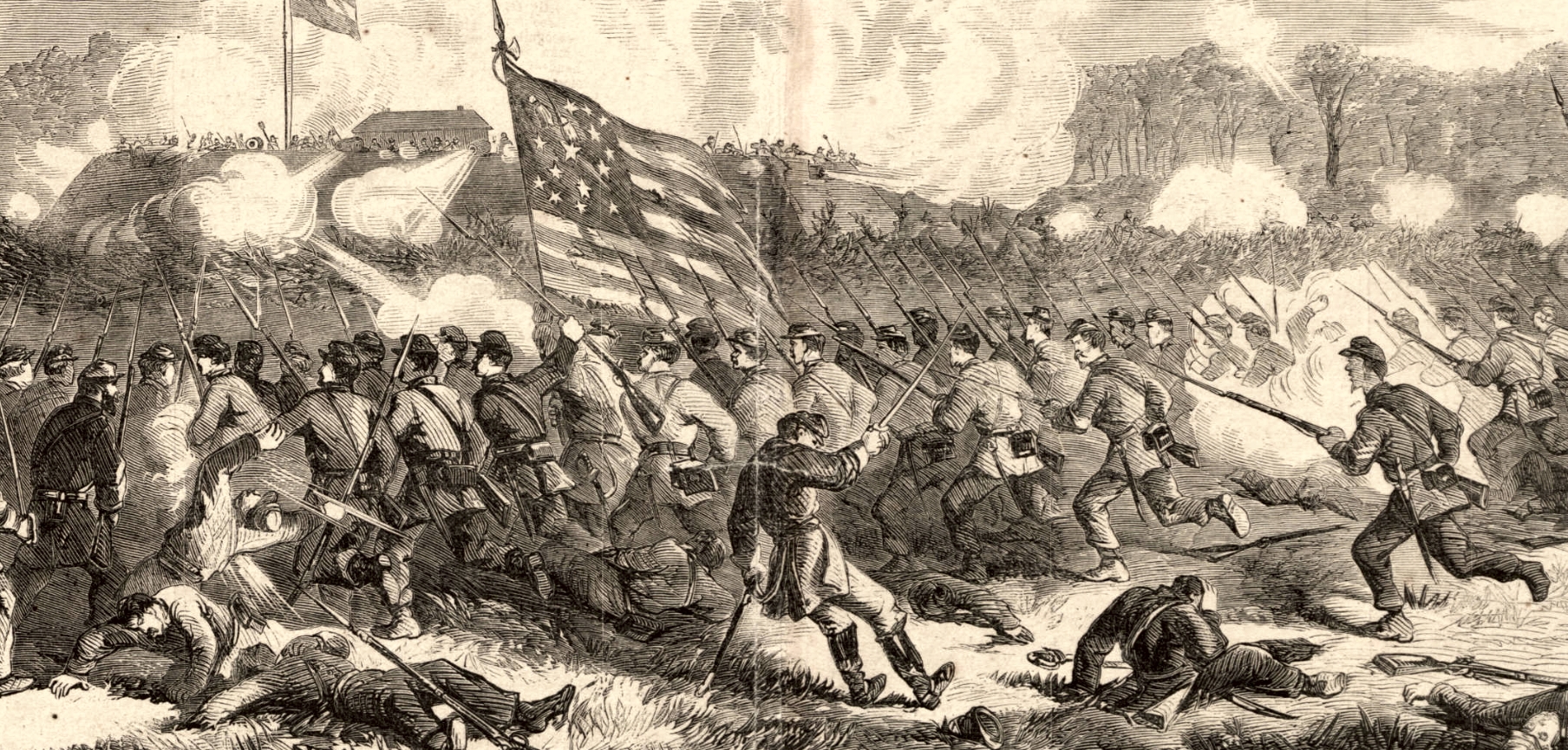

“We have had two battles since we left Camp Steele. The first near Vicksburg and the second one at Arkansas Post. We took about 600 prisoners on that place and a good many cannons. Our regiment was in the hottest fire all day. I used 80 cartridges in about two hours but we did not lose many men. Our company did not lose any this last time though we were in a hotter fire than at Vicksburg. Our regiment lost 3 killed and about 10 wounded.

The bombardment at that place [Arkansas Post] was awful. The whole fort was tore to pieces. The men on it were nearly all dead or wounded. There were 125 artillery men in it and only 20 were left when they surrendered.

At Vicksburg we had to go back without gaining anything. Our company lost five men there—one killed and four wounded. Two of our recruits were wounded. You do not know them but the others you know. [Julius] Zinzer is dead and [Fred] Klingel and [William] Rascher are wounded. This place [Vicksburg] is very hard to take. We are just now going down to try again.”

Taking Vicksburg did indeed prove to be long and difficult task. On March 6, 1863, William Heldman wrote about information he had received from German deserters from Confederate forces.

“There are deserters coming from Vicksburg most every day. They are all Germans. I have talked to one for a long time. He told me that they had to suffer a great deal of hunger. They get only three-quarters of a pound of bacon a week, half a pound of cornbread a day. They don’t know how coffee looks any more. Sugar they have plenty of it and molasses too. Salt is very scarce. They cannot get anything across the river anymore now.”

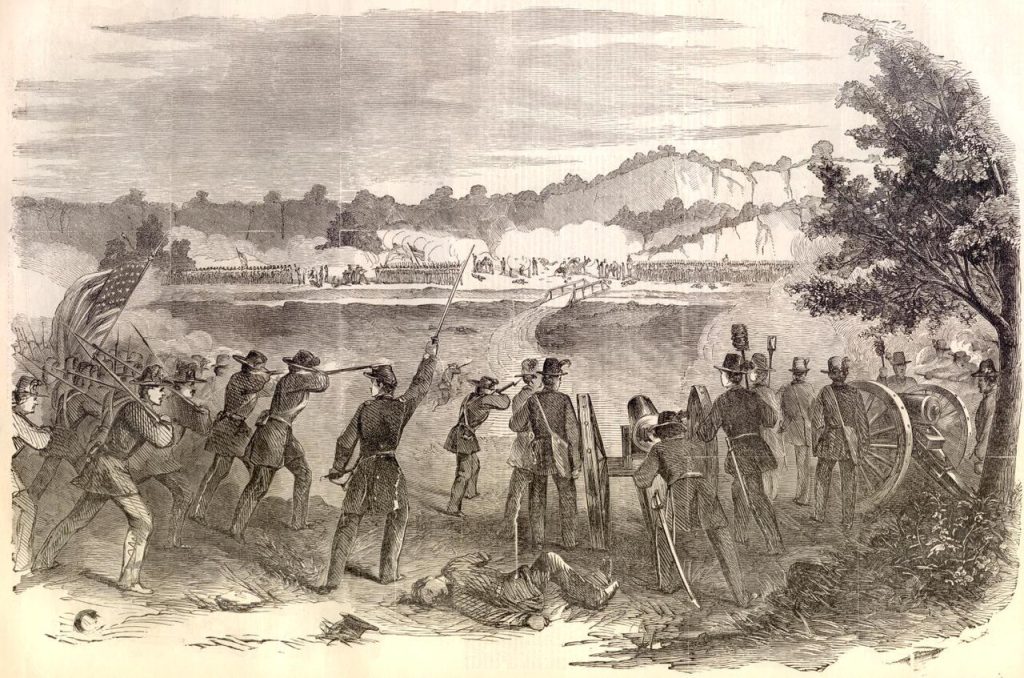

Another letter from June 20, 1863 details the ongoing Siege of Vicksburg and the increasingly difficult position of the Confederate forces.

“We are still in our old place near the river above the city on the right wing. I believe they will soon surrender now. Deserters come over most every night. They all belong to Tennessee regiments. They say they get something to eat once a day. We have got them penned up this time. They can never get out of that place if we won’t let them. Let them attack us in the rear. They will burn their nose if they do. We have got men enough to keep them off. The country is so hilly and rough so that fifty thousand men can keep of a hundred thousand rebels.

It would have been very hard for us to get to where we are if they would have had any of their field artillery left [that] they had out at Black River. They brought 60 cannons from Vicksburg out there. After the battle of Black River Bridge, they had 3 left. The rest we took away from them. They were all scattered and everyone ran for his life to Vicksburg and here we now are.

When we first came here, we had to fight pretty hard. Now we have not much to do. The first day me and [Theodore] Wiegreffe kept a heavy battery from shooting half a day. We crawled up to it in about a hundred yards ad did not let them load their cannons. But the rest of our company would not come there—not a single one of them. The whole company likes us very much for that. The second day I went to the same place and fired about 200 shots. The next night they moved the battery away from that place. Our cannons are all at work today but they do not answer a single shot on this side. The ground is trembling under our feet so hard is the cannonading. Right now one of their large forts is on fire inside right before us on the hill. The powder magazine blowed up just now. Our cannons throw in about 500 shells an hour all around the line.”

On July 4, 1863, the Union army finally took control of Vicksburg. William Heldman survived the war and married Anna Therese Mathilde Summa in 1874. He died in 1912.

We’d like to give a special thanks to William Griffing of Spared & Shared for his work in transcribing and sharing these letters.

To read more of William Heldman’s 41 letters as well as access thousands of other Civil War letters and documents, sign up for a Research Arsenal membership.

If you enjoyed this article, check out some of our other featured collections like Halsey Bartlett of the 6th Connecticut Infantry and Herbert Daniels of the 7th Rhode Island Infantry.